Pentiment

It goes without saying that Obsidian’s Pentiment will appeal to a limited audience. At first, I thought that there might be a cross-section of players that enjoy Obsidian’s open-world epic RPGs who might also have a good time with a game set in and around a 16th-century abbey, they way that Fallout players would likely enjoy The Outer Worlds. But after playing the game, I suspect that the scope of Pentiment’s likely player base is even narrower than I expected. This is a game that is stripped right down to its narrative core, with most gaming “systems” and “mechanics” that normally motivate players forward abandoned in favor of a sophisticated narrative.

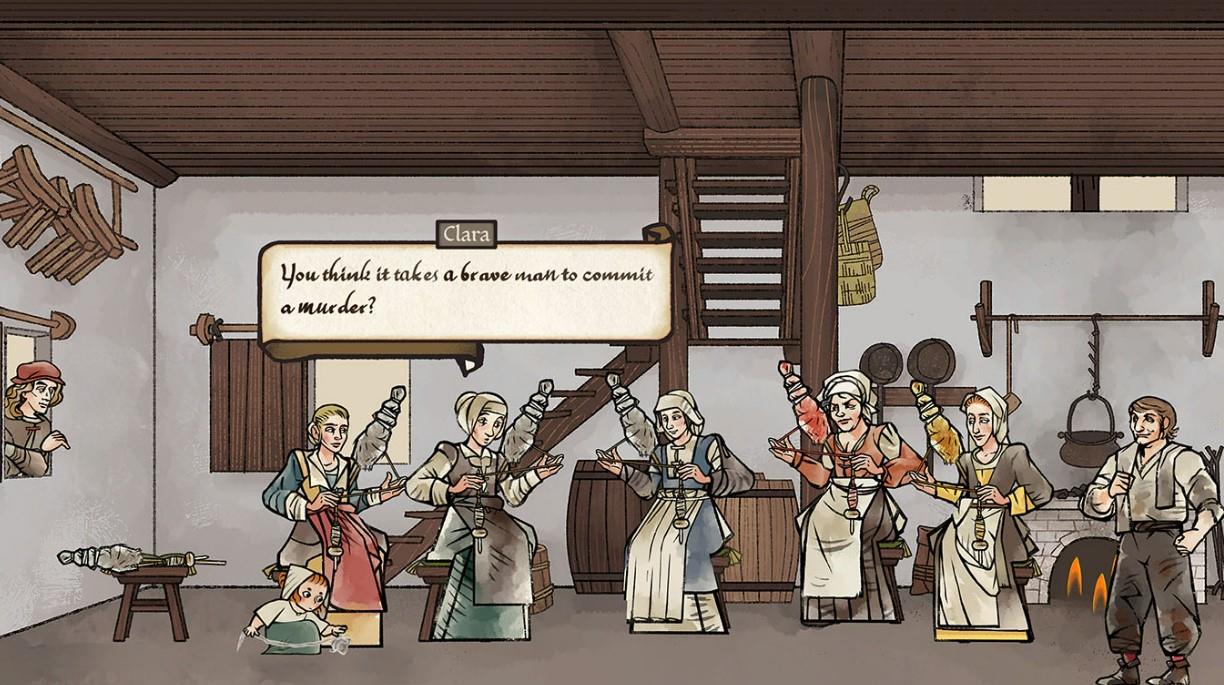

Here we have a game that teeters between the adventure and visual novel genres, without much concern about things like forward momentum, advancement, or even puzzle-solving. The game is played out via very long and intricate conversations with an enormous and shifting cast of characters - all of which must be read, many of which include terms and historic facts that must be researched to fully understand the context of what is happening. The most patient players will find the pace of Pentiment “deliberate”. The other 90% will find it interminable. I imagine about 80% of Game Pass players will take one look at screen shots for the game and say “Yeah, no way.”

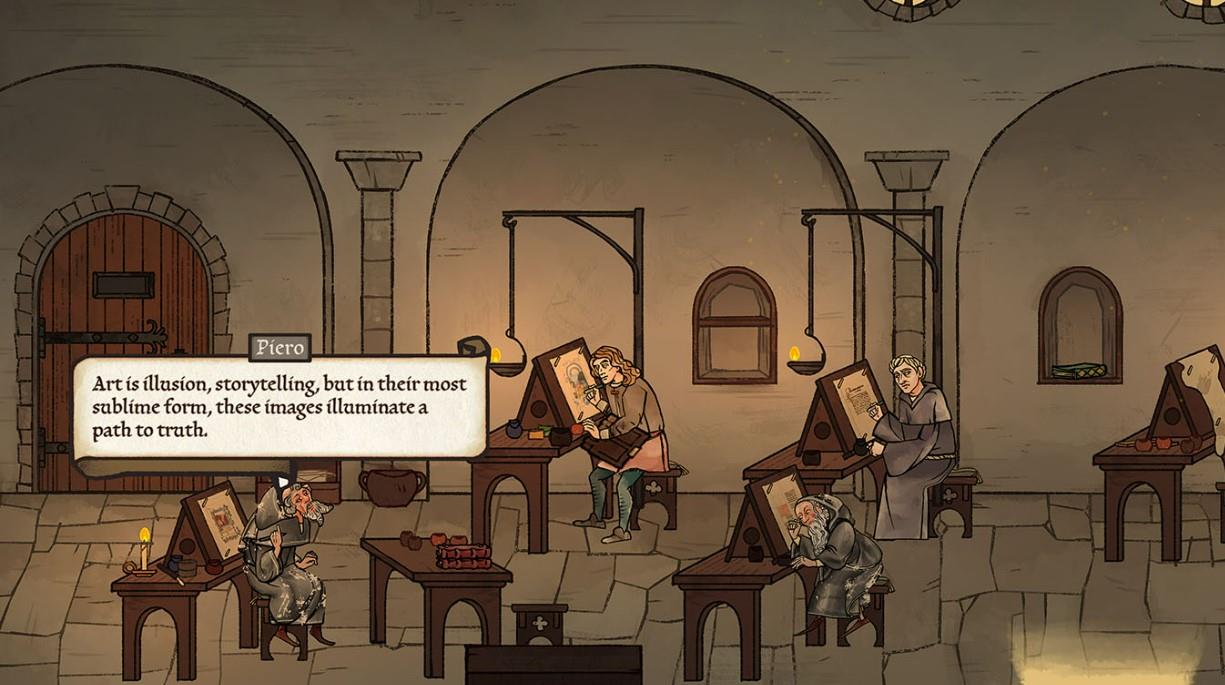

And yet, if there is one thing that Pentiment makes very clear throughout its story, it’s that no work of art can please every audience member. No matter what an artist chooses to create, someone – perhaps most “someones” – is going to be displeased. Its one of the actual themes of the game, baked right into the narrative. As Ricky Nelson said, “You can’t please everyone, so you gotta please yourself.” And I imagine that the folks behind Pentiment are very pleased with themselves indeed, and for good reason.

I’ve often wondered what motivates the Ken Folletts and Umberto Ecos of the world to sit down and create massive works of historic fiction; the task seems overwhelming. Writing the book is only part of the work; first the writer has to have a full understanding of the setting. The creator of a work of historic fiction needs to parse not just the time and place of their chosen location, but also the context; the various religious, historic, geo-political, and economic forces that are impacting their characters. How do these people live on a day-to-day basis? What challenges do they face? What outside forces have influence on their lives? How do they feel about that?

Its very unusual to consider these questions in terms of how a video game is created, though I suppose that for many games the same questions apply. But in the case of Pentiment, the asking of these questions wasn’t just a prerequisite for getting started on the game’s narrative. These questions, in fact, are what the game is all about. Like the writing of a novel or the creation of a video game, Pentiment involves labors that take years to see themselves to fruition, for good or for ill.

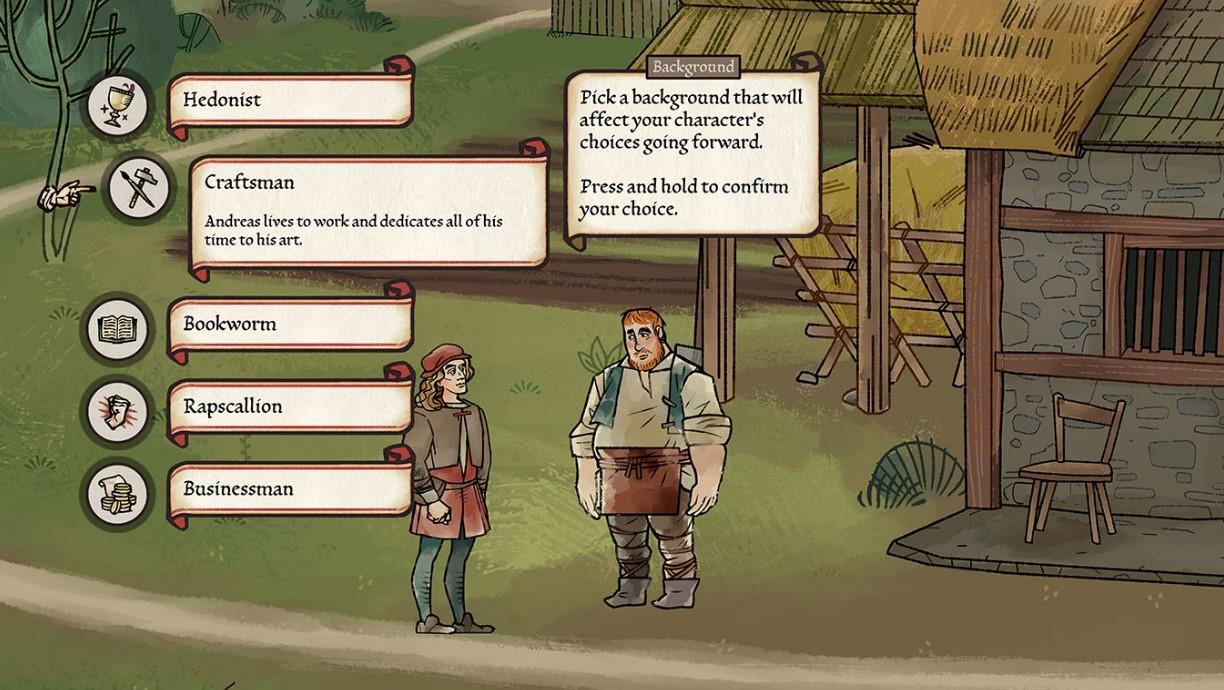

In Pentiment, the player follows through a 25-year period in the town of Tassing, Bavaria. The player starts the game as Andreas, an artist that is staying with a peasant family in town while finishing a commissioned manuscript at the local abbey. As he goes to work every day, Andreas interacts with the various families, peasants, and tradesmen in town, and then navigates the somewhat tricky political structure of the abbey itself, carefully navigating the often surprising personalities of the nuns and monks that live beside - but aside from - the town.

Though life in Tassing seems pastoral and amenable on the surface, resentments between the townspeople, the abbey, and the local lords and barons seem to burble beneath the surface. A complex web of service and taxation exists between the various factions, and no one involved seems to be particularly satisfied with the status quo.

And then a murder is committed, and an obviously not-guilty culprit is quickly named. To help clear the name of the accused, Andreas takes on the role of detective, Columbo-ing around town and talking to everyone that lives there. Along the way, Andreas uncovers secrets, scandals, and half-remembered histories, and maybe even figures out the truth of who the real killer is.

One of Pentiment’s greatest tricks is the way that it obscures information from the player. No matter how hard you try to penetrate the veil of truth, you will never gain the full picture of what is going on beneath the surface in Tassing. There is too much happening, and there simply isn’t enough time. The game keeps pushing the hour inexorably forward, leaving the player to decide which narrative threads to pursue and which to abandon. Getting to the truth is difficult; people are vague, people have forgotten, people are ashamed, people outright lie. Andreas – and the player – will likely end up pointing the finger at someone that may very well be innocent; there was no concept of “reasonable doubt” in 16th century Bavaria.

And of course, the initial mystery facing Andreas is only the beginning. Through their initial investigation, the player learns the layout of the town, the cast of characters, the political structure of the culture. This is all just set-up for the rest of the game. Pentiment moves the clock forward, and then again, allowing the player to explore Tassing as it moves through time through additional major events in the town’s unfolding history. Families fall in and out of favor, older generations die off, younger generations take over the family mill, or start working the fields. One oppressor falls away while another rises to take their place. And of course, what Andreas does in one time period has an impact on the later narrative, sometimes in unexpected ways. Even his hat gets its own little side story.

I’m not speaking much about the game mechanics in Pentiment, because they really are few. Players decide where to go and whom they wish to chat with. Sometimes Andreas is able to suss out some secret bit of information, and sometimes he fails; the story moves forward either way. You will visit and revisit the same locations, and read and read and read, occasionally making a decision. The writing makes the characters feel and behave like real people, but there are a lot of them. The player can be forgiven for conflating some of the characters, and in the end, it often doesn’t matter. Its about the town, really, not the individuals in it.

There is an inevitability to the events in Pentiment, and whatever you do, some major beats in history cannot be changed. But rather than feeling like my decisions didn’t matter in the long run because of the parameters of a video game, I felt more like my actions were defeated by time itself. My Andreas was simply throwing pebbles into a stream, and while the ripples seemed important at the time, the flow of the water is uninterrupted. In the end, Pentiment is about much more than just a murder mystery. It’s about the pervasiveness of time passing, the continuation of families, the way that what we have and the way we live is built on the achievements and losses of earlier generations.

But will video game players have patience for a tale with pacing that, while I would consider myself a fan, even I would refer to as glacial? That depends on the individual player. There are certain triggers that I would say would immediately disqualify a player from trying out Pentiment. There are players that refuse to read anything in a video game, and they are legion. They should stay far, far away from Pentiment. There is no combat here either, and very little in the way of puzzle-solving. Instead there is a gentle exploration of a fascinating historic location, told through some very well-done (and surprisingly cartoonish at times) period art work. This is a game for mature players (and I don’t mean that as agism; there are plenty of younger mature players that would likely enjoy Pentiment).

I found myself wondering while playing Pentiment whether I would have seen it though to the end had I not been reviewing the game. I’ve been known to peel off from a book that I’m not enjoying, and Pentiment at times seems obstinate in its determination to test the player’s patience (really, y’all, did you really need to make the player literally do penance after confession?).

But in the end, I realized that yes, indeed, I would have completed the game. I was invested pretty quickly, and though I figured out the solution to the game’s central mystery pretty early on, I still wanted to witness the evolution of the town and its people.

Upon finishing Pentiment, I had gained an appreciation for the game’s setting and characters, as well as an understanding of some of the themes the game was expressing – including the meaning of the game’s name itself. In some ways, I found Pentiment more rewarding than reading a historic novel or watching a period film, because I got to live in this space for a while. At the end of the game, I felt like I really knew Tassing, and had gone through some things with the town and its inhabitants. The history in Pentiment revolves around a quieter time, which makes for a quieter game.

If you have read through this entire review without skimming, I would say that you are likely the type that would enjoy Pentiment. Give it a shot. See what you think. Write your own history on the wall. After all, art is in the eye of the beholder.

Pentiment is a slow and deliberate novel of a game. Though quite lively at times, this is still a game that asks players to read long, intricate conversations and remember scores of characters in a historic setting. The mystery is interesting, and the history is fascinating, but if these aren’t enough to pull you through, you might want to look elsewhere. For patient players, Pentiment is a game like no other, teaching lessons on history, community, and the nature of life itself.

Rating: 8.8 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Howdy. My name is Eric Hauter, and I am a dad with a ton of kids. During my non-existent spare time, I like to play a wide variety of games, including JRPGs, strategy and action games (with the occasional trip into the black hole of MMOs). I am intrigued by the prospect of cloud gaming, and am often found poking around the cloud various platforms looking for fun and interesting stories. I was an early adopter of PSVR (I had one delivered on release day), and I’ve enjoyed trying out the variety of games that have released since day one. I've since added an Oculus Quest 2 and PS VR2 to my headset collection. I’m intrigued by the possibilities presented by VR multi-player, and I try almost every multi-player game that gets released.

My first system was a Commodore 64, and I’ve owned countless systems since then. I was a manager at a toy store for the release of PS1, PS2, N64 and Dreamcast, so my nostalgia that era of gaming runs pretty deep. Currently, I play on Xbox Series X, Series S, PS5, PS VR2, Quest 3, Switch, Luna, GeForce Now, (RIP Stadia) and a super sweet gaming PC built by John Yan. While I lean towards Sony products, I don’t have any brand loyalty, and am perfectly willing to play game on other systems.

When I’m not playing games or wrangling my gaggle of children, I enjoy watching horror movies and doing all the other geeky activities one might expect. I also co-host the Chronologically Podcast, where we review every film from various filmmakers in order, which you can find wherever you get your podcasts.

Follow me on Twitter @eric_hauter, and check out my YouTube channel here.

View Profile