Narita Boy

Techno-swordsman. New wave samurai. Loving son, ‘80s savant, electro-savior. Narita Boy is a lot of things. Especially if those things are the ego-fueled equivalent of a 14-year-old living out a Tron-loving power fantasy. He is the chosen one. And if Narita Boy had launched a few years earlier, he would’ve had a cameo in Ready Player One.

Like in Ready Player One, there’s a Creator. Behind aviator shades and a cop mustache, the Creator stayed up dark days and bright nights, pounding away at his keyboard, building the Digital Kingdom one red/yellow/blue beam of light at a time. He did it all, I have to mention, to a sick technowave soundtrack worth every dollar as a separate purchase.

For movement, Narita Boy is a side-scrolling platformer that wants you to hate its platforming. For action, it’s a hack n’ slasher that’s a little bit stingy with its slashing. For story, there is a father-son tale set inside a ham-fisted hall of memories and a lorebook that reads more like a glossary of computer terms. At first, anyway. Then the platforming and hacking and slashing and near-JRPG-amounts of dialogue either grew on me or the Stockholm Syndrome fully set in, and I ended up pushing hard towards the end game.

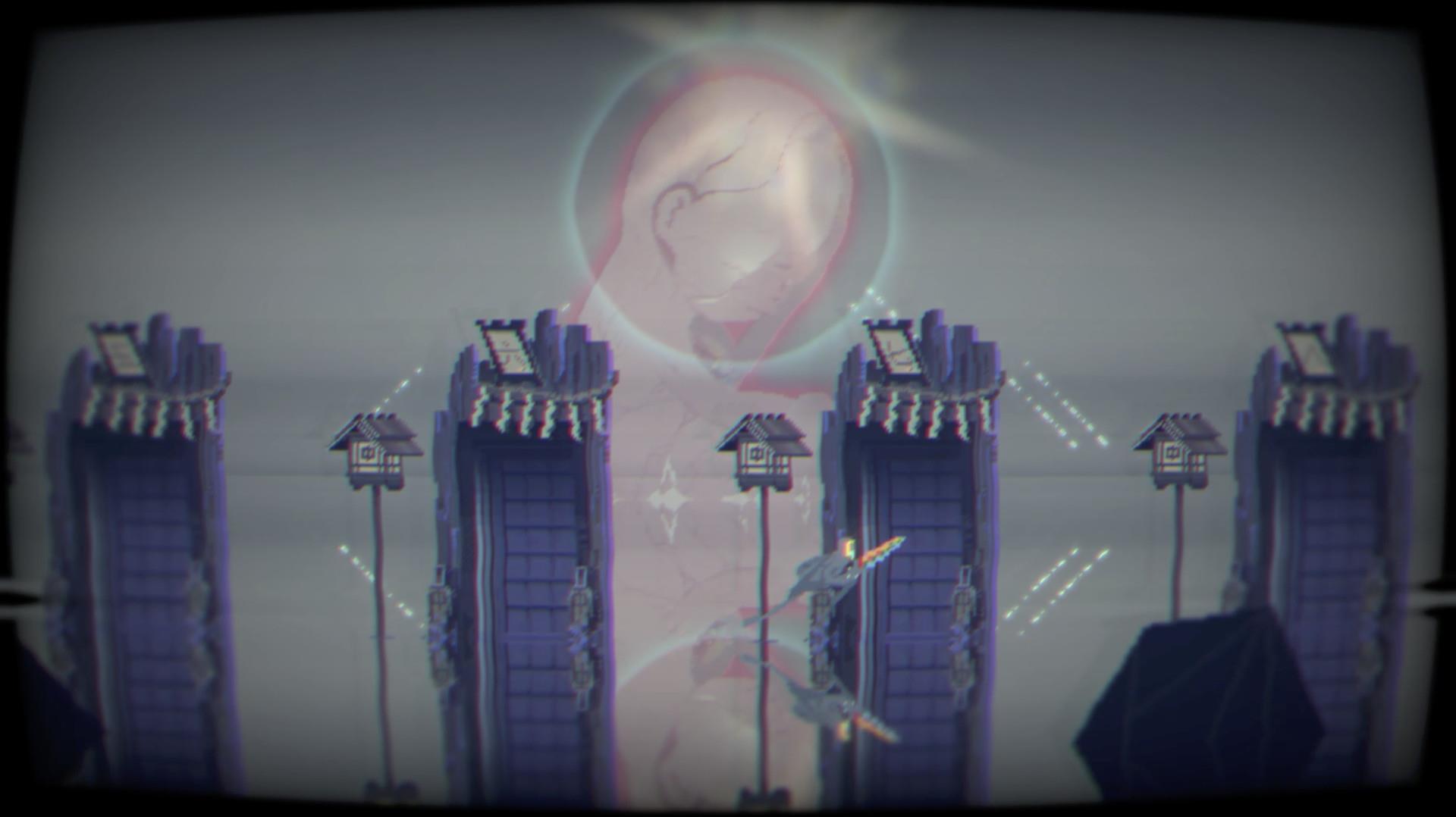

If you go into Narita Boy expecting a top-to-bottom Metroidvania, you’re in for a surprise with how much lore you’ll be reading. For instance, I needed to collect 12 totems. Got it. That didn’t require a repeating 5,000-word monologue from you, Motherboard. And yes, there’s a mother figure named Motherboard. Everything is a capital-M Metaphor in Narita Boy. A game like Hyper Light Drifter, to compare and contrast, is celebrated for its wordless world building. Narita Boy, however, is afraid you’ll miss all the neon signposts if you aren’t stopped in your tracks every few seconds to talk over your mission objectives again. Again, this all happens at first. Narita Boy introduces its world with stuttering steps. Only later does it cut you loose and let the gameplay do the talking.

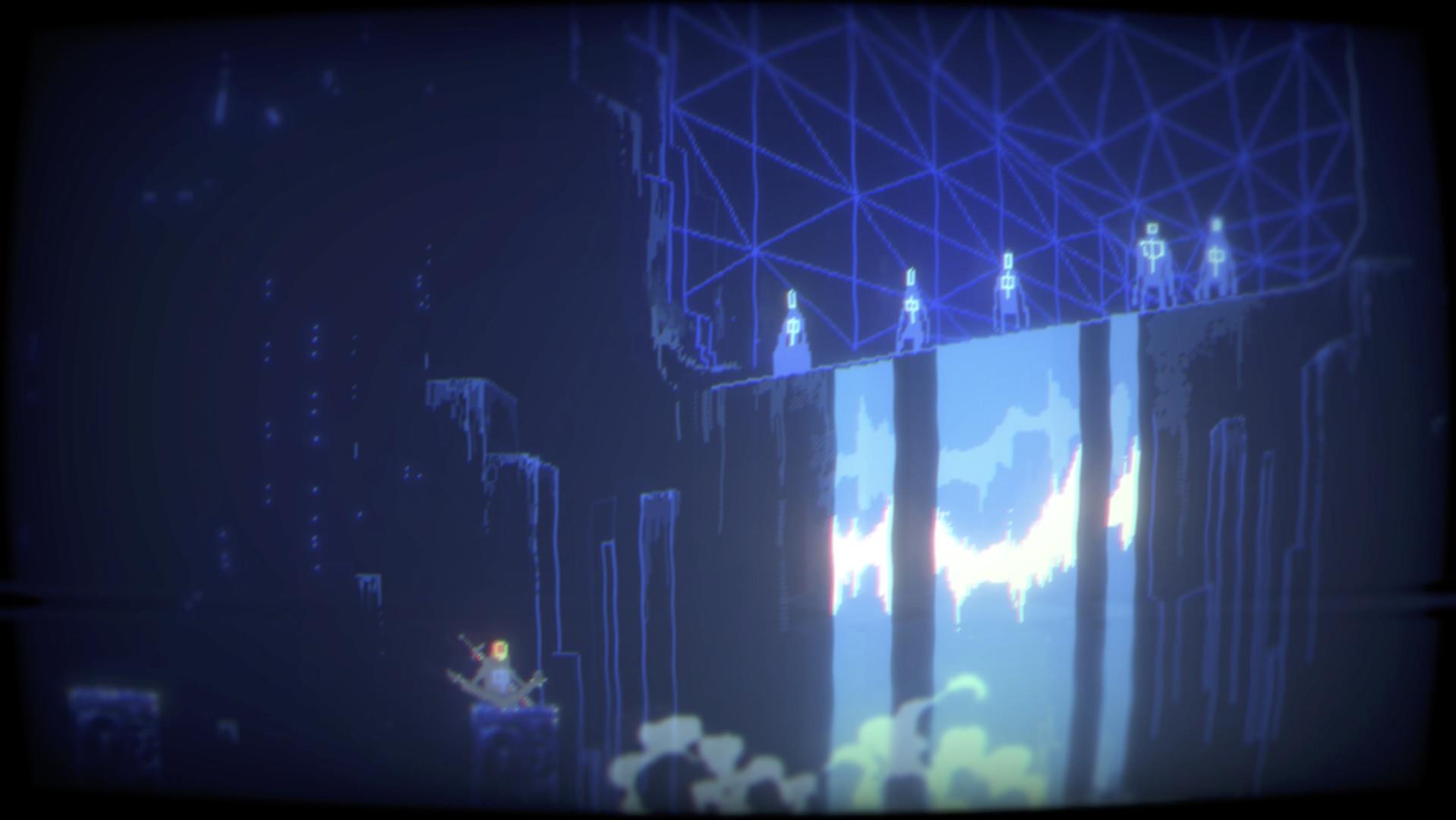

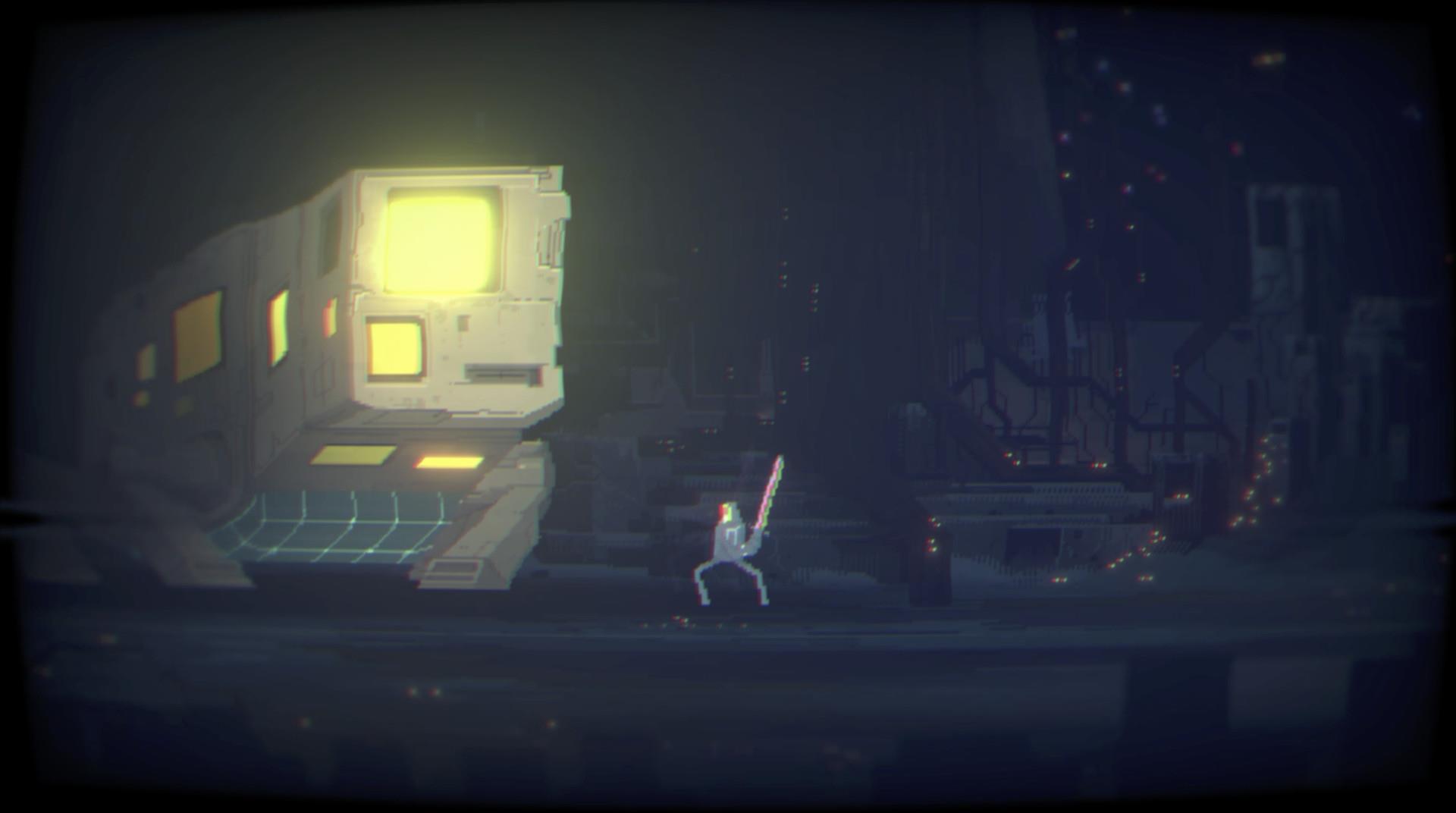

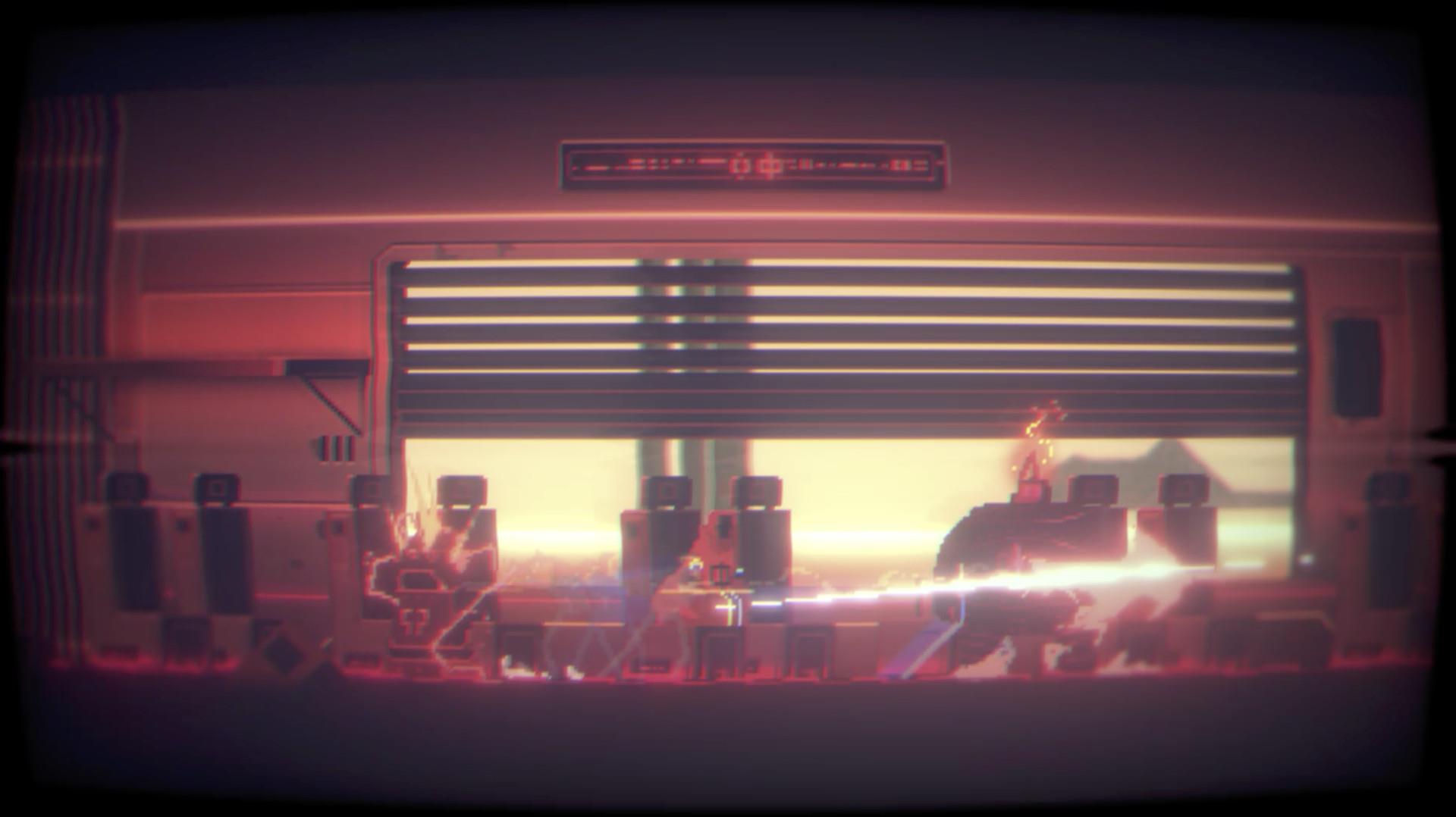

But I’m quickly over Her Royal Verbosity as the digital decay of this CRT kingdom flip flops between chalky opacity and epileptic fits of flashing lights. Every pixelated screen is a glossary of computer programmer words. I pass twitchy sheep grazing the Binary Pastures. Red, yellow, and blue beams shoot out of the digital priests’ faces in the Techno-Algorithm Hall. Twilight lens flare greets me at the Summit of the Perpetual Glitch. Every vocab word you ever learned in Computing 101 is here.

But every screen is screenshot-worthy. Every single screen. I was frustrated by being stopped every few seconds. At the same time, I was glad I was stopped every few seconds. Frustrated by too many words that should’ve been hit harder by a copy editor. Glad from face-melting pixel art that has to be seen to be believed.

The only thing I never got the hang of was the platforming. I moved around better on my Macintosh horse or on my 3.5-inch floppy disk hoverboard much better than I ever got around on my feet. When it comes to verticality, Narita Boy reminded me why I dislike up and down exploration in side-scrollers. Lose your grip on a slippery set of wall jumps, and it’ll feel like Narita Boy is Getting Over It With Bennett Foddy. Nail the climb or take the fall of shame.

There’s so much back-and-forth in the levels, too. Was I backtracking because I missed something, or backtracking because I got the keycard to a door 10 screens away? It was getting harder and harder to tell. For as many blinking, pointing fingers and arrow signs as there are, they only felt moderately helpful. I stumbled across forward progress accidentally as much as on purpose.

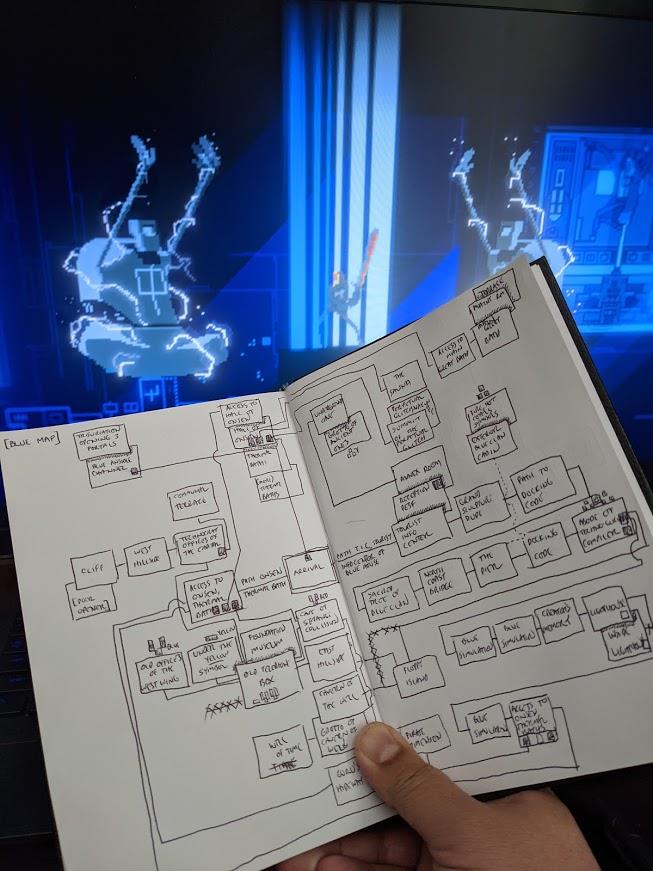

Until I figured out once again, in the year 2021, how to draw a map. I think the last time I drew a map was back in the Sierra adventure game days. Back in the brutal King’s Quest era. When the map wasn’t some pretty game box pack-in burned into cloth. To get through Narita Boy, what I had to draw were those functionally ugly lines-connecting-squares kinds of maps. I don’t even own a pencil, let alone an eraser, so I started drawing maps in pen, complete with mistakes and wrong turns and, frankly, bad enough penmanship that it wouldn’t be helpful if another player tried to use my screenshot as some kind of guide.

No, you don’t have to draw maps to get through Narita Boy. But I sure did. I was so lost by the second level that I didn’t have a choice. And I loved it. Drawing these maps became the highlight of my gameplay. It added hours to my playthrough, but I wouldn’t have survived the back-and-forth without indulging in map making. Despite turning itself into an in-the-vein hit of neo-nostalgia, it’s the time I spent with pen and pad that actually tapped into my genuine nostalgia for this era.

Narita Boy’s only real shortfall in the beginning is that it won’t just let you play. That’s all I wanted to do at first. I just wanted to swing my techno-sword and explode a few techno-zombies. But it’s so bent on talking your ear off about its world-building. Like it doesn’t think it’s worthwhile to hack and slash some bad guys until you have the game world’s entire mythology mapped out for you. It doesn’t want you taking too many swings until it’s front-loaded the concept that you’ve got 13 levels to deal with. Don’t hop around too much until you’ve internalized all of this computerized religion, my boy. Could’ve told twice the story with half the words and left a greater impact on the player.

Several design choices feel off, at least for the first few hours. The jump is barely manageable, until you learn how to slide in the air. Landings are slippery, until you learn how to drop it like it’s hot. Sword swings make your very first enemy bounce away from you, until you learn how to shoulder check them rather than whiff your third swing. So, technically, the platforming and the fighting get better, but only because they start at an unusually low point.

I want to stress that I don’t think the writing in Narita Boy is bad. Not bad bad. It just desperately needed an editor to pare it down to the essentials. Carve out its more interesting details, and leave the dullest parts of its exposition on the cutting room floor. It felt like Narita Boy’s writers were getting paid by the word, leaving the text bloated, and leaving me glossy-eyed. The two sides of this game, action vs. adventure, rarely seem in concert with one another.

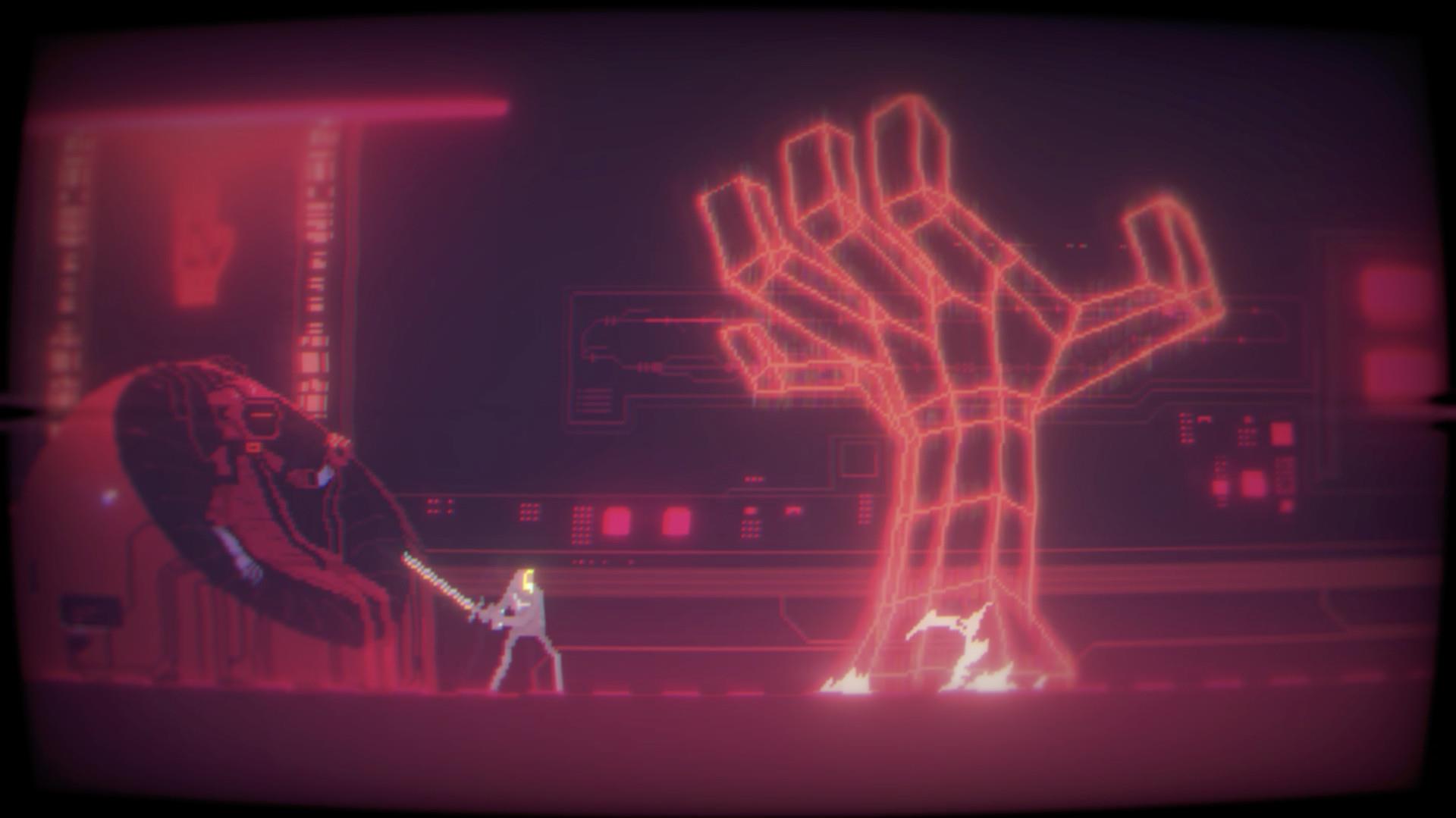

But there are some neat surprises in its gameplay. It’s a place where whale watching off Floppy Island reveals a symbol that will unlock a doorway. It’s also a place where every boss fight makes you step back and ask yourself, Now what is this new devilry? But don’t forget that it’s also a place that will instantly drown you in a puddle of water from one bad jump, killing you quicker than a boss fight.

Unfortunately, the denizens of this techno kingdom have no stories themselves. Everything is in service to Narita Boy’s narrative. Beyond the religious business of worshipping this Motherboard character, or bowing down to this or that enormous screen-faced guru, there’s nothing else to learn about their computerized lives. They’re as shallow as a single line of programming.

That’s all part of Narita Boy’s power fantasy. He’s still the chosen one. He’s still their only hope. Hurry. Hurry to the growing variety of enemy combatants. Hurry to the unlocking platforming and sword-swinging skills. Then slow down, breathe in the sights, and soak in the monologues. I had to read the text in different character voices, and I had to draw maps in an old journal, and I had to rage quit and calmly return to a couple boss fights. Once I’d taken those extra steps, I found a lot to like in a game that didn’t want me to like it at first. But in the end, the pull to see every stage, fight every boss, and follow this digerati narrative through to its inevitable conclusion was undeniable.

Rating: 7.4 Above Average

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile