BioShock: The Collection Review

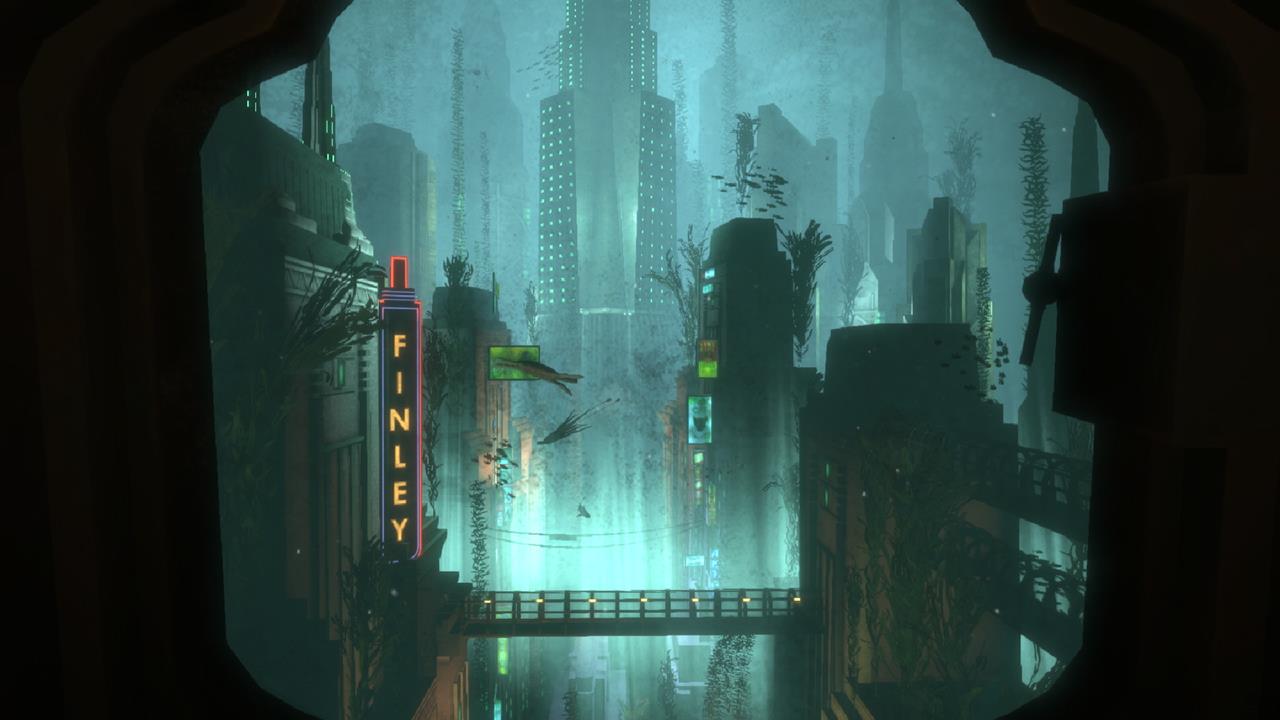

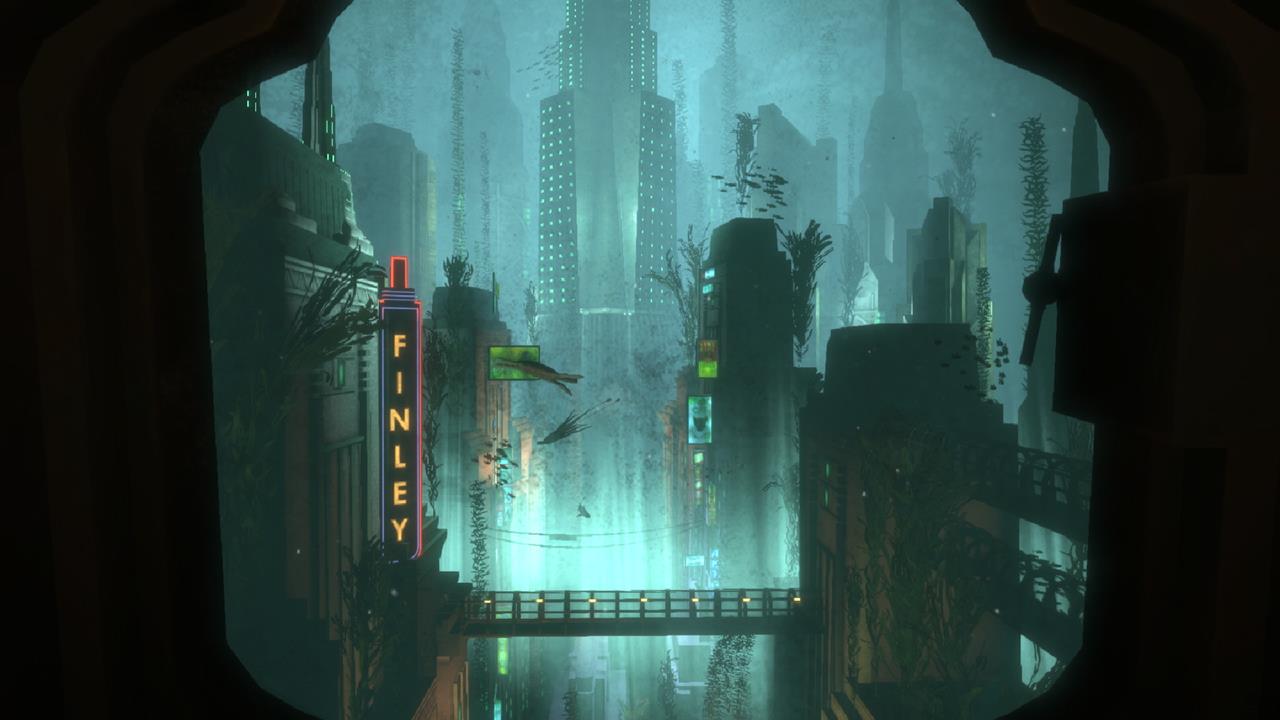

First impressions are pretty important. For a lot of gamers, Ken Levine and Irrational Games’s first-person horror RPG BioShock made one hell of a first impression. The opening plane crash, the novel setting of a ruined underwater objectivist utopia, Andrew Ryan’s stirring, chilling opening monologue, it all added up to a tour-de-force that kept people enraptured for the whole ride thereafter. I was not one of those people, and revisiting the BioShock trilogy for its Nintendo Switch release brings back a lot of memories.

I won’t bury the lede however. If you want the short version, this is a fantastic port of the BioShock trilogy for Nintendo Switch. Virtuous Games and Blind Squirrel have outdone themselves, maintaining a nearly constant 30 fps at a dynamic resolution that looks crisp in both docked and portable mode. Great work all around, and since there really isn’t a whole lot more to say about this port, I’d like to explore why these games are so timeless, what they mean to me, and why you should absolutely pick them up on Switch if you haven’t already played them, or are just keen to revisit them.

In August 2007, I was a starving college student who had just built a new gaming PC, eagerly anticipating the spiritual sequel to 1999’s System Shock 2 that creative director Ken Levine had finally gotten off the ground. I distinctly remember spending another $60 on BioShock, its shimmering iridescent box art gleaming in the afternoon sun on the way back to the car. Then I got it home and played it, or rather attempted to.

For a number of gamers like me, BioShock was a mess at launch. BioShock frequently and randomly crashed on me, mocking my smartly optimized new rig. Trying to reinstall it didn’t help, and threw up another roadblock: the game’s stranglehold SecuROM DRM interpreted this as multiple users installing the game on the same machine, and it got cranky with me. You could reinstall BioShock a measly two times before you had to call tech support to get more online activation keys. As a final insult, the game’s widescreen mode wasn’t even true widescreen; it didn’t widen the FOV, but instead simply chopped the top and bottom off a 4:3 aspect ratio and zoomed the image in.

These issues infuriated me and neatly stripped the luster and hype right off BioShock, which in turn led me to put a much more critical eye to the game itself. The RPG elements, so complex and elegantly interwoven throughout System Shock 2, were dramatically scaled back, one might even say dumbed down. The shooting mechanics were stiff and awkward, juggling them against the genetic plasmid powers never felt natural, and the whole game creaked and strained on the shaky foundation of the aging Unreal 2.5 engine.

In terms of plot and setting, the initial trailers portrayed a Cronenbergian nightmare about trading your body and soul for genetic superpowers, but in the actual game that felt like so much set-dressing when the real focus was Ken Levine complaining about Ayn Rand for several hours. The Art Deco halls of Rapture, while striking, made me suspicious that Irrational had stolen a lot of Rapture’s visual kitsch from the Fallout series. And to top everything off, BioShock just wasn’t all that scary. It was definitely in your face with all the gore and brutality, but it lacked the restraint and subtle, creeping dread of System Shock 2. The claustrophobic corridors of the Von Braun, lit just dimly enough to play tricks on your eyes, were far more anxiety-inducing than the lurid, neon-splashed, blood-spattered halls and atriums of Rapture, constantly populated with a scramble of crazy Splicers muttering silly things to themselves.

In the years since, as the technical bugs were squashed and the borderline criminal DRM was removed, my ire toward BioShock has softened. After I reframed my narrative expectations, I came to appreciate what its plot was saying, and that mid-game twist is legitimately brilliant. I understand that the gameplay is a little clunky on purpose, to put you off-balance and emulate the experience of a terrified man coming to grips with the mutations he’s injecting into his arms. I still have issues with BioShock; I wish the ethics of the Little Sisters and Big Daddies was the real focus of the story, instead of a horrifying symptom of the ideological struggle that underpins the narrative. I wish the moral choice that the game presents you with, and the resulting endings of the story, weren’t so jarringly binary. And man oh man, I still cannot stand that Pipe Dream hacking minigame.

All that said, BioShock has really grown on me. Having it on Switch humming away so smoothly, where I can take it anywhere, is a hell of a thing. I wouldn’t say it’s one of my favorite games, but amusingly it’s one that I’ve replayed quite often, probably because, for all its flaws, its setting and gameplay loop are so effortlessly compelling. The siren call of Rapture still pulls me in all these years later.

In contrast, BioShock 2 was the opposite case for me. I un-ironically call BioShock 2 “the good one” and it is one of my favorite games of all time. I came to it a few years after it released, and after many others had dismissed it for a variety of reasons, I struggled through its rough first impression to dig into the brilliance that lay just below BioShock 2’s choppy waves. Directed by Jordan Thomas, a level designer on the original game who crafted its haunting Fort Frolic stage, BioShock 2 had a strong foundation but was again plagued by technical issues. A lot of the game’s nuts and bolts felt rushed and shaky, Unreal 2.5 was really starting to show its age, and the visuals that had been so striking three years earlier were starting to look a little rough. Worst of all BioShock 2 was saddled with the nauseatingly awful Games for Windows Live DRM client, a needless bloatware frontend that nobody liked or asked for. This was like piling bricks onto a card house, and made getting the game running smoothly on PC into a herculean effort. Thankfully these issues have all been fixed in recent ports, but even a couple years after it originally launched in 2010, BioShock 2 was a real bear to get running.

BioShock 2’s intro also does it no favors. Far from the gripping, in-engine ocean reveal of Rapture in the original, BioShock 2 begins with a pre-rendered flashback sequence to the 1959 New Year‘s Eve party right before the fall of Rapture. It’s pretty lore-heavy and probably bewildering to anyone who hasn’t played the first game. But for people who do understand what’s going on, people like me who fought and struggled just to finish the original BioShock before it crashed again, this opening cutscene is arresting. You’re viewing that fateful masquerade party through the eyes of a Big Daddy, led by the hand by a Little Sister through a crowd of startled partygoers. You engage in a battle to save her from Splicer thugs, and then a statuesque woman hypnotizes you, hands you a pistol, commands you to remove your helmet and shoot yourself in the head. All in front of the horrified eyes of your Little Sister.

BioShock 2 is about the last, crumbling days of Rapture. A new tyrant, a psychologist named Sophia Lamb who was “disappeared” to a political prison during Andrew Ryan’s rule, has returned and whipped the remaining Splicers into collectivist cult. While Lamb was in prison her daughter Eleanor was abducted and transformed into a Little Sister, and you play as Subject Delta, another political prisoner who was changed into a Big Daddy and genetically bonded to Eleanor. Sophia Lamb is pursuing a collectivist utopia, and is trying to use the biological mad science of Rapture to turn her own daughter into the “first utopian,” a genetically engineered messiah. To escape this horrifying fate, Eleanor arranges to have Delta resurrected a decade after Lamb made him commit suicide, so he can come and free her before her mother can do the unspeakable.

Wow. I was hooked. BioShock 2’s first hour might be a little slow and it doesn’t have the visceral impact of Andrew Ryan’s iconic monologue, but all I could think about was how good it felt to be back in Rapture, and how much I wanted to figure out what had been happening while I was gone. Once I pushed through the technical hangups and narrative frontloading, I realized that everything, literally everything, about the first BioShock had been improved in the sequel.

All of the base mechanics have been streamlined and improved. You can now wield Plasmid powers and weapons at the same time, one in each hand, instead of having to awkwardly swap between the two. The weapons are meaner, more potent, and strike a good balance between brutal power (you are an armored tank of a man after all) and vulnerability (you aren’t invincible). The plasmids have been refined, with many of the redundant abilities and stat-boosting gene tonics either excised or smartly consolidated. Level design is more efficient and circular, resembling a 3D Metroidvania, aiding exploration and the setting of traps. And thank God, that hacking minigame has been simplified into a quick moving needle puzzle, which speeds up the process but also places it in real-time, so you’re vulnerable to damage while hacking.

The gameplay also goes full-bore into the game’s main thematic concept: You are a Big Daddy, and the relationship between you and the Little Sisters is front and center. You still have the tense miniboss battles from the first game where you have to liberate Little Sisters by killing their tank-like Daddies, but now you can adopt the Sisters and protect them as they gather Adam from corpses. This adds a tower defense element which encourages setting traps, hacking security to fight for you, and smart use of offensive tactics and Plasmids. This protector mechanic dovetails nicely into the game’s story, which elegantly juggles multiple themes and ideas.

BioShock 2 tackles the idea of Sophia Lamb’s cultish form of collectivism, the complete disregard for the self in favor of the common good. She’s obsessive about it, to the point where she’s willing to callously torture her followers, perform hideous experiments on her closest friends, and ultimately impose a fate worse than death onto her own flesh and blood daughter. Whereas Andrew Ryan was arrogant, naive and condescending, Lamb is cold, calculating and ruthless, with just a perverse hint of “it’s for your own good” maternal warmth. It’s fascinating to watch her unravel as the game progresses; she begins as a detached dictator, confident in her own ideals, only to undermine those ideals as she grows more and more frustrated with her daughter’s disobedience, up to the point where she’s willing to murder Eleanor and everyone else to avoid acknowledging that she’s wrong.

The most potent way the game plays with these ideas is in the mechanic of choice. While the original game’s tagline was “we all make choices, but in the end your choices make you,” I felt it was a check that BioShock couldn’t really cash. The decision to rescue or consume the Little Sisters didn’t have steep enough consequences to the minute-to-minute gameplay, and the ending was too black and white. BioShock 2 matures this concept into something truly masterful. You still choose between harvesting or rescuing Sisters, but they’re relying on you as their Daddy to keep them safe. They start out acting like enthusiastic little kids, excited to see you after a long day, but if you harvest more and more Sisters, they start to recoil and cower like abused children. I still feel BioShock 2 doesn’t get enough credit for uncomfortable little details like this. But this choice mechanic goes even further. BioShock 2 isn’t just about Lamb’s collectivism vs. Ryan’s objectivism. It’s also very much about the importance of adoption, and the gravity of being a parent.

Throughout the game you encounter three key NPCs, major players in Lamb’s cult. These characters replace boss battles (a smart move; BioShock’s end boss fight wasn’t very good) and throughout the levels and storyline these characters make your life, and sometimes Eleanor’s, really unpleasant. There’s a strong inclination to resent and even hate these characters by the end of each major act in the game, and in time they each end up standing before you, at your mercy. There are valid arguments either way for sparing or messily murdering each one, but it’s not just you, Subject Delta, that has to live with the consequences. As you deal with each Little Sister and these three main characters, meting out life or death in turn, Eleanor is watching the whole time. The brilliant twist here isn’t something like the first game’s “would you kindly,” it’s that you do not make the final decisions in the game—Eleanor does. She decides the fates of the last Little Sisters, Subject Delta and even her own mother. BioShock 2 has six total endings, three main and three variations, and they all hinge on how you acted, Eleanor’s interpretation of your actions, and how they determine her final choices.

BioShock 2 reminds you that as great or as humble as you might be, the people who depend on you are always watching, evaluating, and applying what your example teaches to their own gestating beliefs, moral code and ultimately their decisions. Long after you are dead and gone, you are still the voice in their ear, the angel, or devil, sitting on their shoulder. In a cultural landscape where fathers are so roundly mocked, belittled and dismissed, BioShock 2 quietly states that being a good dad is one of the most challenging, rewarding and important jobs in the whole world. Whether by blood or adoption, you are one of the Most Important People to this fresh, vulnerable little life, so please take great care in this most humbling responsibility. I’m not ashamed to admit that I’ve wept at the end of this game, but as an expectant father myself, today it hits home with particular impact.

BioShock 2 also includes a DLC chapter called Minerva’s Den. It’s a small but affecting story about Charles Milton Porter, Rapture’s lead computer engineer, and how he tries to recreate his dead wife, lost during the Blitz, with Rapture’s core AI. It’s about loss and acceptance, as you follow Porter’s final journey to escape from Rapture and what he decides to take with him. It’s a wonderfully poignant dénouement for BioShock 1 and 2, and for all intents and purposes, I consider it the end of the Rapture story.

Far from the “direct to DVD” sequel that so many fans and critics write BioShock 2 off for, this game is the culmination of everything this series set out to accomplish. It’s one of the rare sequels that retroactively makes its predecessor better. It both expands and tightens the gameplay, but just as importantly it brings the plot full circle. BioShock was about a conman who blundered into paradise, cornered the market on genetic superpowers, and exploited the cracks in a naïve visionary’s ultra-capitalist dream. BioShock 2 was about a charismatic psychologist who ignored the wisdom and pitfalls of her own profession, and pushed Marxist collectivism to the point where she’d sacrifice her own daughter to fulfill her delusion of “the common good.” The whole Rapture story, then, is a warning: no matter how good the intentions, any philosophical ideal pushed to its ideological extreme ends up at fascism. If you relentlessly pursue a vision and ignore the unpleasant nuances and complications of human life, it ends with you dismantling the freedoms of the people who say “this doesn’t add up.” The only thing you have to look forward to after that is the inevitable Brutus sticking a shiv in your side, and seizing your dream for their own twisted ends.

As Eleanor says, with that the Rapture dream was over. So…where do you go from here? It turns out the sky’s the limit, and that phrase was never so apt as it was in the case of BioShock. The third game in the series, BioShock Infinite, marks Ken Levine’s return, although Jordan Thomas later came aboard as an advisor and writer. Infinite takes place in a different world and even universe than the first two games: the floating sky city of Columbia in 1912, a perpetual World’s Fair and icon of American exceptionalism. Columbia began as America’s technological envoy of peace and prosperity to the world, but was commandeered by its governor Zachary Hale Comstock. With the most advanced quantum technology in the world at his disposal, Comstock secedes from America, declares himself the prophet of a new religion, places his followers into a protected class, and relegates blacks, Irish, Italians and any other “lower” races into a perpetual state of indentured wage slavery.

You play as Booker Dewitt, a disgraced, alcoholic ex-Pinkerton detective charged with rescuing Comstock’s daughter Elizabeth from Columbia. Your motivations are unclear, and as you infiltrate Columbia, reality and your reference point to it start to fall apart. Key to all this is Elizabeth, who possesses a terrifying power that is prophesied to bring ruin to the world. The setting, characters and themes are heady, challenging stuff, and at surface level they appear to be deep, profound and important. That said, like the first BioShock, I feel that Infinite never lives up to its aspirations, or even the gameplay standards of its forebears.

I have pretty mixed feelings about Infinite. It had a torturous seven-year development cycle, and it shows. I recall Ken Levine saying that they left five or six games’ worth of material on the cutting room floor and man he wasn’t kidding. To start with the positives, Columbia is an absolutely breathtaking locale. Nearly a decade later and it’s still jaw-dropping, just stunning to look at. The uncomfortable classism and late 1800s xenophobic influence, juxtaposed against the genuinely gorgeous old-fashioned, small-town glory of mid-history America just drips from every corner of Columbia. It instills an uneasy, compromised sense of nationalist pride, and Irrational deserves all the credit in the world for nailing the aesthetic they were going for.

But once you dig into Infinite’s gameplay, the cut corners and sacrificed ideas start to become clear. The pre-release trailers portrayed an active, dynamic world where your choices could turn the people of Columbia against you, or rally them to your cause in real-time. Your partnership with Elizabeth was vital, as her powers to bend reality and call in storms, weapons and effects from other dimensions could be decisive in a pitched battle. These trailers also hinted at a series-defining boss battle with a giant mechanized monster call the Songbird, Elizabeth’s obsessive jailer and protector.

The final game plays like an awkward, compromised hybrid of BioShock and Call of Duty. The combat, while tight and fast, also feels mechanically abbreviated. The persistent NPC ecosystem of the first games, which balanced the hostile splicers and neutral Big Daddies against each other and the player, is gone entirely, replaced by scripted, cover-based encounters with groups of enemies and the occasional miniboss. The hinted-at dynamic loyalty system is nowhere to be found. While in BioShock 1 and 2 you could carry an entire arsenal of improvised steampunk weaponry, Infinite limits you to two guns at a time. Confusingly these weapons also have upgrade trees, but without the ability to carry them all, you’re forced to stick with whichever weapon has the most ammo lying around. The plasmids, now called vigors, also feel less compelling. There are less of them but a couple feel strangely redundant, and gene tonics have been replaced with an inconvenient set of equipable gear. Hacking has been completely replaced by the “possession” vigor that lets you temporarily turn enemy robots, and eventually humans, into allies.

Once you’ve teamed up with Elizabeth she can aid you in combat by tossing health and ammo powerups out at convenient times, or by activating obviously scripted “tears” in reality to call in a gun turret, or an ammo dump, or a balloon sentry robot. This is a far cry from what was shown in those early trailers, like Elizabeth dynamically calling in a thundercloud which you could turn into a deadly storm with your Shock Jockey Vigor. As a final let-down, that awesome Songbird boss is defeated in a cutscene.

While functional, everything about Infinite feels cut off at the knees. This is no more apparent than in the story, and the concept of choice, which was so integral to the narratives of the first two games. Infinite takes this concept and actively undermines it. The entire story is about how your choices don’t matter; without going too far into spoiler territory, the plot is about the existence of the multiverse and how, with an infinite number of eventualities, nothing you do changes anything in the grand scheme of things. The developers took this concept as far as to build it into the level architecture; the maps have multiple left-right branching paths that put you at the exact same destination, with no consequence of the path you chose. Outside of these pointless diversions, the level design of Columbia, while beautiful, is painfully linear.

While I enjoyed the interplay between Booker and Elizabeth, and Comstock is a genuinely menacing villain, a lot of it feels cliché. There are some intriguing questions about plural realities, but like everything else in the game, they feel surface level and aren’t explored in much depth. You don’t get much thematic analysis beyond racism=bad, or good guys can do bad things, or again, your choices are meaningless. The game’s big twist, clearly trying to live up to the legendary reveal in the first game, comes off as pithy and derivative, and anyone who’s watched an episode of The Twilight Zone can see it coming a mile away. There’s also a fairly contrived explanation as to why Columbia’s vigors are so similar to BioShock’s plasmids. Infinite’s ending and DLC chapters attempt to leverage its concept of infinite universes to tie the narrative into the first BioShock, but it comes off as an eye-rolling stretch and, in my opinion, actually damages the narrative integrity of the first two games.

BioShock Infinite is not a bad game. Its mechanics, while shallow, are tight and entertaining, and it has a setting and visual style that are breathtaking even today, and I do recommend you play it to experience the whole trilogy on Switch. That said, for me at least Infinite was deeply disappointing, and I consider it one of the all-time most overrated games of the last generation. So much of what was shown pre-release was severely cut down or absent altogether in the final product, and what could have been a genuine masterpiece that truly deserved all the praise heaped onto it by critics, clearly fell victim to scope creep and a marathon crunch sprint to cut the fat and get the game out the door.

BioShock is ultimately the story of ambition. It’s a series about lofty ideals undone by the inconvenient realities and nagging details of human nature, and the unscrupulous people who prey on those blind spots. It’s about aspirational game design and storytelling, sometimes compromised and crippled, and other times enhanced by the technological limits of the day. BioShock is a complicated, challenging series. I can’t feel mostly positive or glowingly praiseful about its stories, gameplay or themes the way I can about Metroid Prime, or Zelda or Half-Life. It’s an uneven franchise, but one that absolutely commands your attention. It lives up to its name as the thinking man’s first-person shooter. If you’ve never played the BioShock games before, you really should, at least once, and the new collection on Nintendo Switch is the perfect opportunity. If you already have, it might be time to revisit Rapture and Columbia. I guarantee you’ll fight, and struggle, and think, and happen across some meaningful detail you missed the last time around, just as I did.

The BioShock trilogy is still three masterpieces that demand attention. While the first game hasn't aged particularly well, the sequel never got the recognition it deserved, and the third game is ultimately pretty disappointing, but they're still all worth another playthrough. The Switch port is masterfully done, smooth and crisp, and a great way to experience these games for the first time or revisit them.

Rating: 9 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been gaming off and on since I was about three, starting with Star Raiders on the Atari 800 computer. As a kid I played mostly on PC--Doom, Duke Nukem, Dark Forces--but enjoyed the 16-bit console wars vicariously during sleepovers and hangouts with my school friends. In 1997 GoldenEye 007 and the N64 brought me back into the console scene and I've played and owned a wide variety of platforms since, although I still have an affection for Nintendo and Sega.

I started writing for Gaming Nexus back in mid-2005, right before the 7th console generation hit. Since then I've focused mostly on the PC and Nintendo scenes but I also play regularly on Sony and Microsoft consoles. My favorite series include Metroid, Deus Ex, Zelda, Metal Gear and Far Cry. I'm also something of an amateur retro collector. I currently live in Westerville, Ohio with my wife and our cat, who sits so close to the TV I'd swear she loves Zelda more than we do. We are expecting our first child, who will receive a thorough education in the classics.

View Profile