Death Stranding

"Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." - United States Postal Service creed

Meet Sam Bridges. Sam Porter Bridges. Mail courier, seeming germaphobe, and backpacker extraordinaire. He’s the kind of guy that only smiles when he’s alone in front of a bathroom mirror, but he’s also okay with wearing an otter hood made for him by a cosplayer. Sam Bridges has range in every way possible. And about that name: the Death Stranding was an apocalypse that basically bombed the planet back into the Dark Ages. Everyone now seems to take on their occupation as their surname. Hence “Porter.” Hence “Bridges.”

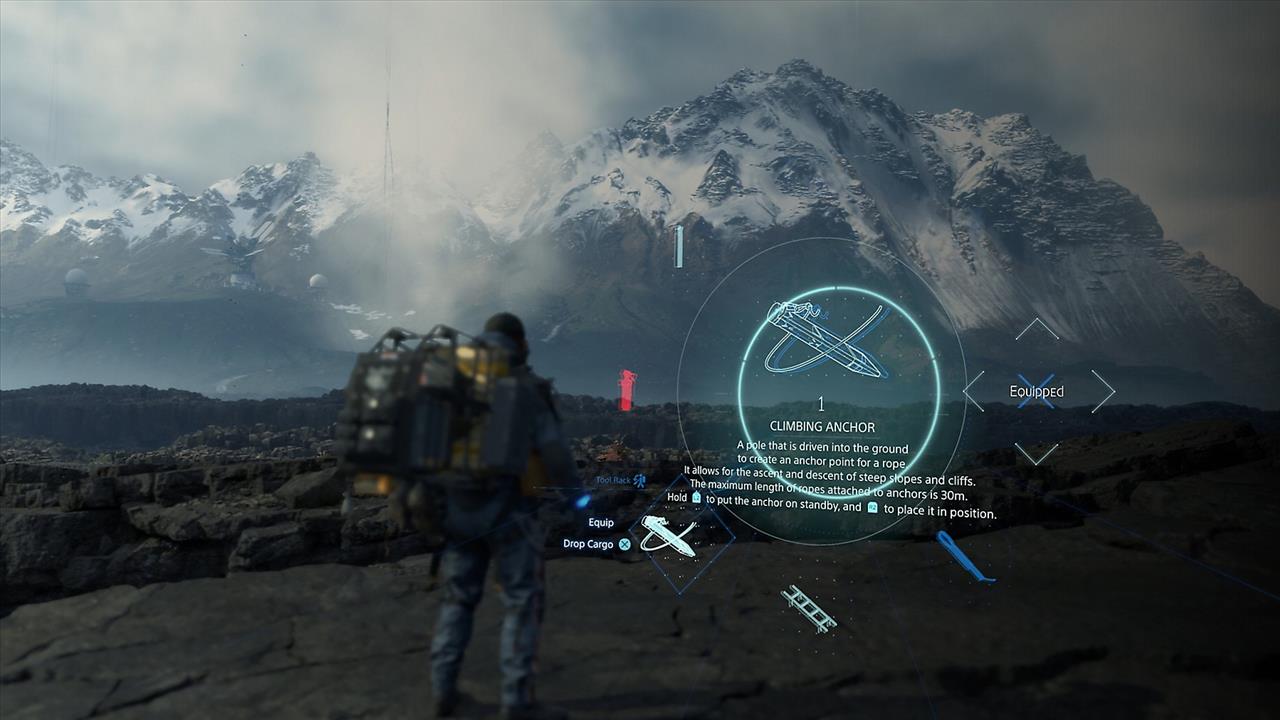

Death Stranding is a logistics simulator. But instead of building roads and hauling cargo from a SimCity point of view, you get a boots-on-the-ground view of the FedEx-fueled action. A game where you’re continually cherry-picking the path of least resistance across the National Geographic landscape. Where you’re constantly having old adages crop up in the back of your mind: Watch your step! Look before you leap! Mind the gap! It’s a game of visual extremes, where the ground textures belong in Outside Magazine, but your inventory menus are crammed with 2D line drawings of lookalike gear.

Kojima is here with a message of hope. That was the most surprising takeaway I had from Death Stranding. It’s not about getting knocked down. It’s about getting back up. It is a nearly impossible task representing this recovery and reconstruction across all of post-apocalyptic America. But he does it with a pie slice of artists and engineers, doctors and spiritual leaders. Sam Bridges works to reconnect an isolated and disparate people, one delivery at a time. Sometimes he delivers a precious photograph back to someone. Sometimes it’s fuel for the winter. Sometimes it’s a body bag filled with a loved one.

Death Stranding goes some places.

Everywhere Sam Bridges goes, he’s treated like a bonafide hero. Which makes it all the more startling when you find someone who isn’t impressed with him or the logistics company he works for. But Sam Bridges is a hero in our age where seemingly the only heroes are anti-heroes. The more antihero they are, the more awards they rack up in movies and television.

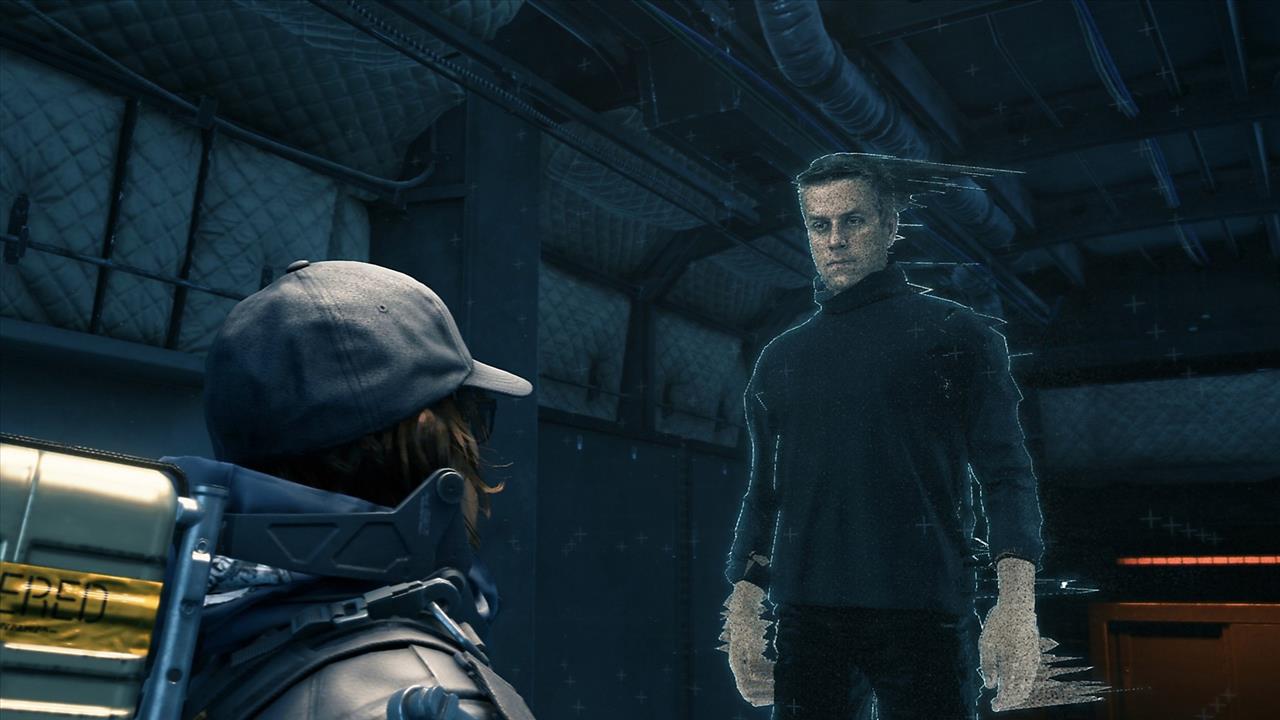

It’s a weird world out there for Sam Bridges. Invisible creatures leave oily handprints on the ground. Walking Dead actors stroll naked along the beach and shed tears over unborn babies kept alive in embryo jars. The only currency is Likes from social media. It’s a game that has you decide between going to the bathroom while standing or sitting, with the resulting bodily waste turned into anti-ghost grenades. You think I’m kidding.

Kojima seems to be having a blast making this game. But there are tough topics, too. Motherhood. Surrogate fatherhood. Terrorism. Environmentalism. Cremating a parent. Aborting a baby. Japan’s continuous conversation about being nuked in World War 2. All of it being dealt with by a man that’s expected to reconnect hearts and minds across America, but has a phobia of physically shaking another person’s hand. Thankfully, while Death Stranding is never afraid of giving the player a wink and a nod, its hardest subjects are handled with a deep understanding and a level of maturity I wasn’t entirely expecting.

You know how some games, if they’re good, give you one of those “musical moments”? One where the very expensive licensed music kicks in during a contemplative moment in the protagonist’s journey, solidifying the gravity of the situation at hand? Well, Death Stranding feels like it has one of those musical moments every hour—across the span of a game that, for me, inched up to the 100-hour mark. Death Stranding’s pop music sensibilities never get old. Ridiculously pretty music is your most faithful travel companion across a broken United Cities of America (not a typo).

The musical connections don’t just crop up in the soundtrack. Your communicator chimes the first few notes to Rock-A-Bye Baby when somebody rings you up. You know, “rock-a-bye baby on the treetop?” Another device chimes “London Bridge is falling down.” You know you’re in Kojima Land when children’s lullabies and nursery rhymes begin to inform the nature of gameplay. It’s wild.

Kojima relinquishes directorial control for long swatches of time, but is more than willing to take you through five of the 12 steps in a Hero’s Journey before you even hit chapter 2.

Death Stranding is a third-person logistics simulator, if I were to be reductive, but the biggest rewards are waiting for explorer-type gamers. This is the first game since Skyrim where exploration is king. You’re making deliveries, a post-apocalyptic postman, carving a beeline from A to B, drawing out and running down your science-fantasy UPS delivery route, all across a stunning array of geographical biomes and topographical extremes. Instead of ammo you’ve got cargo. Instead of ghillie suits you’ve got suitcases. Instead of jumping out of dropships you’re filling up dropboxes.

Well, you’re actually armed and armored later on. Stuff gets real out there for Sam Bridges. But by the time they hand you a gun, it’s startling. It’s a frightening revelation that you’d be capable of killing someone else. Death Stranding is a logistics simulator, yes. But stealth—or just running for your life—is entirely called for in dangerous encounters. And who knows? You might just make it through this thing without taking a single life.

The entire cast of characters have names that are so bad they’re good. Like they’re Mega Man bosses. Death Stranding has Deadman, Heartman, and Die-Hardman, for heaven’s sake. Mama and Fragile make up the leading ladies of the cast, which continues to bring up questions regarding Kojima’s relationship with the women in his life. The weirdest part is that it all starts to make sense. Those early trailers with all the crying, the babies in the sand, and beached whales? Those, too, all start to make sense. There’s a ton of Kojima Logic at work, but it’s smart stuff. It’s not that Metal Gear Solid 5 brand of nonsense where “she wears a bikini top because she breathes through her skin” stuff. Death Stranding is frighteningly brilliant in explaining itself—even if we’re still talking about a video game in a built-from-scratch science-fiction universe.

While this is a single-player game, there’s limited multiplayer interactions. You can post warning signs or build small logistics structures all across the map, and your signs and structures can appear in other people’s games. Just like their signs and structures can appear in yours. It’s great. If I had to build every dropbox, ladder bridge, and safehouse from one end of the map to the other, I’d be exhausted.

Knowing the mountain climbing gear I built is getting Likes from other players, or me giving Likes to the people that cooperatively (in their single-player games) built an actual bridge across a deep, rushing river? That’s where Death Stranding gets meta in its message of connecting people. Sam Bridges is bringing people in the UCA closer together—while you, the player, are brought closer to other players through your building projects. Heck, it’s worth handing out a Like when you come across a cheerleading “You can do it!” sign at the top of a particularly nasty hill climb. It cost nothing for that player to post that sign, and it cost you nothing to hit the Like button. Yet it works out great for both players.

I’ve never looked worse in a video game than when I’ve been caught by the ghosts. I was dragged a hundred yards through the black oil at ground level. It was an inky black squid that caught me that first time. Left me looking like I’d taken a bath with a bunch of Bic pens. And it left a massive, impassable crater on the map. It was devastating. I was devastated. This much terrain deformation is unheard of.

Kojima declared that he’s created a new genre: the stranding genre. It often takes a lot of retrospection to know when and where a new genre is created. It takes years. We only started labeling some games as “roguelikes” in the last few years, but we label them after a game from 1980. I’m 100 percent skeptical that many (if any) game developers can follow in Kojima’s steps in Death Stranding. I’ll grant that he’s breaking plenty of molds. There’s no arguing that. But whether or not a proliferation of “stranding genre” video games hit the market is doubtable. And that’s no criticism. Kojima has singularly struck out on his own. He’s nothing short of a trailblazer.

A trailblazer that sends mixed messages about masculinity and male sexuality. It’s a game where you can stare at Norman Reedus’s butt every time he takes a shower. Yet, if you try to zoom the camera into his crotch while he’s fully clothed, he’ll eventually punch the camera. Seriously.

Really, my only complaints center around a very few quality of life issues. The cargo menus, for example, desperately need to be sorted by destination. Or by cargo type. Having to flip through a hundred individual entries just to find one or two packages going to, for instance, the Wind Farm? That’s too much squinting and scrolling. And when taking on deliveries, I’m feeling like I have to confirm things one too many times, or I’m being railroaded out of the menus before I’m fully loaded. I eventually picked up what the menus were putting down. I got better and faster at negotiating their quirks. It just felt like there was a two-factor-authorization happening when single button presses would do the job.

I don’t know if this is a good or bad thing, but I felt my work ethic strengthen around this game. Like I knew that it was work to play it, but I was enjoying the work. And you know what they say: If you love what you do, you’ll never work a day in your life. That expression has only barely ever made sense to me. Until now.

I grew slowly and steadily afraid that all of these Hollywood actors wouldn’t amount to much. I saw the tears streaming down their faces in the trailers, but hadn’t felt any of them had earned mine. Then a particularly moving performance by Margaret Qualley as “Mama” nearly broke me. Wiped away all my skepticism after that.

Death Stranding isn’t about an apocalypse. It’s about the reconstruction afterwards. Vince Lombardi, whose name is on the NFL’s Super Bowl trophy, once said, “It’s not whether you get knocked down, it’s whether you get up.” That’s what Death Stranding is about. Getting back up. All the way up from all the way down. It’s an ode to the American Dream, which could only come from a designer outside of America, since—let’s be real—the American Dream has been oversalted in nothing but irony ever since Rockstar started making Grand Theft Auto.

I began to get something of a Tetris Effect when I wasn’t playing. I’d see the different textures in the grass, rock, water, and snow, passing before my eyes in a slow cascade downward. It all seemed to be leaving a ghostly image in my mind, since so much of Death Stranding is spent looking down at the ground, with quick glances up to make sure you’re still headed in the right direction. I welcomed the cascade during my working hours.

Sam Bridges is drawing a new Oregon Trail across the land. But this time it’s a trail of the friends he made along the way.

Hideo Kojima has fully weaponized the walking simulator, writing a love letter to the delivery service workers of our shipping and handling world. Death Stranding is about ending isolation, and does it so gracefully that I can't imagine it being done better than it's done here.

Rating: 9.5 Excellent

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile