Inside

When I reviewed Playdead’s Limbo a few weeks ago, I touched on how the game’s ambiguous, potentially religious themes capped off the latent paranoia and obnoxious guilt complexes I developed from growing up Catholic. The vagueness of the game’s atmosphere, the callousness of its world, and the indirectly hostile indifference of the whole thing toward its fragile protagonist certainly made me feel all sorts of a certain way. As I move on to the spiritual sequel, Inside, I’m beginning to think Playdead should rename their studio to Bad Things Happening to Children, because it seems to be a consistent theme in their work. Inside definitely shares several gameplay and thematic concepts with Limbo, but paradoxically the less ambiguous, more expressive story and setting key off of a far more primal set of phobias and revulsions, at least for me.

Limbo is about being lost and confused; Inside is about running scared. Ostensibly, both games are pretty similar. They are both about a frightened young child battling a hostile environment, but whereas Limbo takes place in a shadowy forest somewhere between heaven and hell, Inside is set in a twisted version of the real world. You begin the game as the aforementioned frightened child, running through the forest as a nameless authoritarian force tranquilizes and rounds up the civilian populace. You get the clear implication that this regime has a fate far worse than death in store for our protagonist, as you stumble through fields full of livestock—many slaughtered, but others infected with mind-control parasites.

It’s clear there is a mass-scale culling and enslavement happening, and it’s painted just as starkly and lacking in pretense as the grisly horrors of Limbo. That said, it feels a hell of a lot scarier and more immediate than Limbo because it’s portrayed as being a lot more real; after all, a nightmare is still a dream, painted in grim but fleeting shadows, but Inside feels like something that might just happen in the real world.

Mind control seems to be a common trope in Playdead’s games. To evade capture, the protagonist is forced at points to imitate the brainwashed people around him in a frighteningly elegant movement tutorial. I’ve never seen a video game use basic up-down-left-right-jump mechanics to drive a point home just quite like this. As you progress further, you’ll be able to plug your protagonist’s head into literal mind-control devices; helmets that let you move seemingly brain-dead “husks” of people around to accomplish simple tasks. Maybe I’m just easily squeamish, but a lot of this stuff sent an oily chill down my spine.

There seems to be a heavier emphasis on timing with Inside; the platforming challenges usually happen when you’re being chased or evading capture. A lot of the time you’ll take a tranquilizer dart to the neck, or get grabbed by Taser tentacles and dragged off screen. Other times you’ll be chased down and torn to shreds by hungry attack Dobermans, and the obstacles are always more mundane than the chasms or traps in Limbo. Often the only thing standing between you and temporary safety is a chain link fence or a boarded up door, and the mundanity of these situations makes figuring out the timing or the puzzle a little trickier than Limbo’s admittedly more video-gamey puzzles.

Inside also expands upon its settings more than its predecessor and this also diversifies the gameplay. Your character can swim (whereas Limbo Kid drowned in more than a couple feet of water) so diving for short periods of time is a way to avoid detection, and later on a way to explore flooded areas and complete puzzles that alter the depth and direction of water. I was surprised at one point later in the game where you steal a small submersible and proceed to crash through underwater ruins. And…well, the frustrating part is that if I explain any more of the gameplay I’ll spoil the rest of the story, and you really need to play this game to the end, possibly more than once, to get the full effect.

Without going into detail, things get weird toward the end of Inside and there are even two endings, both of them less ambiguous than Limbo’s abrupt conclusion, but with more dangling plot threads and implications that your brain will be chewing over for days. A lot of fan theories suspect that Inside is saying something about player agency and what it means to interact with a fictional character by means of the limited, but potent, conduit of direct bodily control. Then again, Inside lets you make up your own mind and, just like Limbo, it is decidedly bereft of pretense or heavy-handed moralizing, preaching and finger-pointing, which I find refreshing, especially from an indie game.

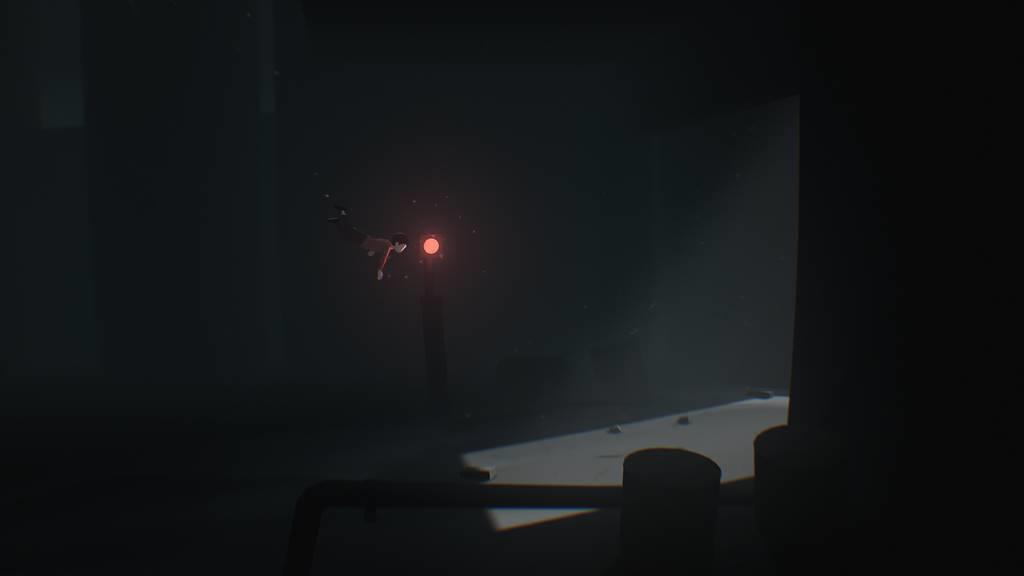

Inside’s very color palette is more pronounced than Limbo’s monochrome forest, albeit still muted. Hazy grays and shadows make up the background, while the characters are presented in stark, flat-shaded tones that look like heavy charcoal or construction paper. It’s dark and grim, but kind of elegant too. It’s as if Wes Anderson was having a really terrible day, watched The Road, and decided to write and direct something similar. Lighting is especially impressive in this title, setting an omnipresent mood of dread while also gently guiding the player along the path to success without standing out too much. Inside’s production values are a stark contrast to Limbo’s; while that game was all about black-and-white contrast portraying a nebulous story, Inside uses subtle color and tone as a backdrop for a much more direct and immediate plot.

Like Playdead’s freshman effort, Inside is just one of those games you have to play at least once. Now that both Limbo and Inside are on Switch, I feel these games have found the perfect platform to reach a broader audience. Like Limbo, Inside is brief, unpretentious, emotionally arresting and well suited to portable play, both for its bite-sized nature and the ease of sharing it with friends when you happen to have your Switch stowed in your backpack. Every self-respecting gamer should add Inside to their indie Switch library.

Like Limbo, Inside is short, mechanically addictive and emotionally haunting. It’s the perfect addition to the Switch’s growing library of now-portable indie hits.

Rating: 9 Excellent

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been gaming off and on since I was about three, starting with Star Raiders on the Atari 800 computer. As a kid I played mostly on PC--Doom, Duke Nukem, Dark Forces--but enjoyed the 16-bit console wars vicariously during sleepovers and hangouts with my school friends. In 1997 GoldenEye 007 and the N64 brought me back into the console scene and I've played and owned a wide variety of platforms since, although I still have an affection for Nintendo and Sega.

I started writing for Gaming Nexus back in mid-2005, right before the 7th console generation hit. Since then I've focused mostly on the PC and Nintendo scenes but I also play regularly on Sony and Microsoft consoles. My favorite series include Metroid, Deus Ex, Zelda, Metal Gear and Far Cry. I'm also something of an amateur retro collector. I currently live in Westerville, Ohio with my wife and our cat, who sits so close to the TV I'd swear she loves Zelda more than we do. We are expecting our first child, who will receive a thorough education in the classics.

View Profile