Detroit: Become Human

At first, Detroit: Become Human appears to be little more than a game that gets its rocks off with child endangerment, hamfisted slavery analogies, and good cop/bad cop tropes. At first, the game acts like it’s simply a place where physically ugly humans are bad, and immaculately beautiful androids are good. Detroit is a city where androids are “stealing our jobs,” even if we neglect the jobs we already have, like tidying up the living room, washing the dishes, or raising our kids.

Some of these pared-down sci-fi archetypes travel the width and breadth of Become Human. But these are still stories worth examining. Especially when placed within a well-realized game world, one you can interact with. Yes, this is a Quantic Dream adventure game, which means interaction is in the form of lots and lots of quick time events.

But hey, before we all start acting like quick time events should’ve died off 10 years ago, let’s consider the idea that a game as cinematically minded as Detroit: Become Human doesn’t rely on gun triggers and sword swings to negotiate its game spaces. Like developer David Cage’s previous titles (e.g. Indigo Prophecy, Heavy Rain), your movements aren’t always about reloading guns and donning armor. They’re about translating the mundane onto the gamepad. They’re about putting away groceries, wiping down kitchen counters, and tucking the kiddo into bed. So, if that’s not how you like to use your gamepad, you should take a hard pass on Detroit: Become Human. You'll be missing some cool stories, though.

Every chapter ends by showing you the branching timeline of your choices. It shows the path you took, and hints at the paths you could’ve taken, and does it without revealing spoilers. The best part, a trick first employed by Telltale Games and its point-and-click adventures, is to show you global stats of what other players did in relation to you. Fifty-six percent of players had Connor choose this. Or perhaps only 13 percent chose that. Seeing those statistics has the strange ability to either reaffirm or dash your hope in humanity. Good, you say to yourself. Nearly 80 percent of people did what I did in that instant, which was, of course the right thing to do. Good job, me. You too, humanity. Or, maybe this chapter concludes in a way that only four percent of other players saw. What is even going on in the world? Am I a monster, or is everyone else a monster? Probably everyone else is a monster.

The narrative itself can be rich, but these global statistics create a metanarrative layer on top of everything else. They reinforce the idea that you made these choices, not some video game character.

Developer David Cage operates with the care of a slightly mad scientist. He has the eye of an overpowered creator. As if his video game is crafting our android-run future rather than just crafting a fiction. He imagines himself to be the artistic harbinger of the coming AI apocalypse. To his credit, however, these scenarios don't seem all that far fetched. At least what leads up to these scenarios doesn't seem that far fetched.

What does personal freedom mean when you, as an android, are only allowed to go where you’re told to go and do what you’re programmed to do? In any other game, these are perfectly acceptable parameters within the point-and-click genre. But here is where it takes on deeper meaning because of the subject matter. You’re an android. You live your life on rails. You don’t go upstairs until you finished your tasks downstairs. You don’t get on the bus unless you’re departing point A for exactly point B.

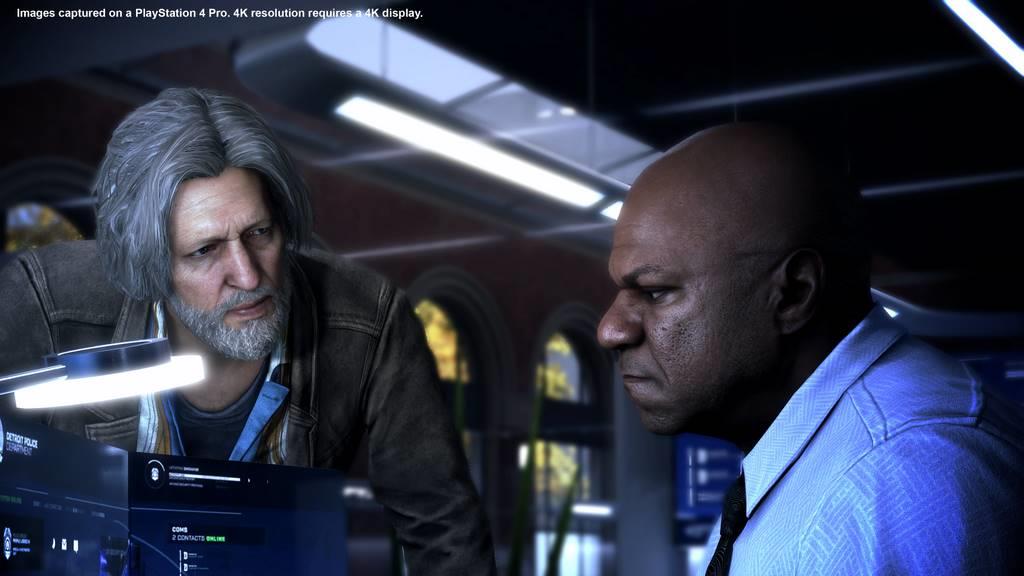

Three narratives interweave in Detroit: Become Human. There’s Connor the law enforcement android. There’s Kara the domestic engineer android. And there’s Markus the caretaker android.

It can be rough playing as Connor. As a member of law enforcement, he sees people at their worst. He pieces together the evidence of people’s depravity, and not just the murderous parts. He sees how people are willing to live in filth and decay. How they adorn refrigerators with pictures of naked women, adding to a growing list of vices that now includes gluttony, pornography, and probably drug abuse.

Kara’s perspective isn’t any easier. Rather than seeing a person’s destruction after the fact, she’s right there in the home watching it happen in real-time.

And what about Markus? He’s a caretaker. He’s lucky enough to be taking care of an enlightened, artistic, philosophically sound old man. But that old man is still dying. And the last time I checked, the death rate in humans is still at 100 percent, which means Markus gets to contemplate death and dying to a degree most androids don't have to.

I don’t know why I wasn’t expecting this, but Detroit goes into some dark places. I’m not just talking about the threat of child abuse either. I’m talking horror. When you reach the android junkyard, it’ll show you a vision of Hell they don’t talk about in Sunday School.

There’s platforming on a level I’ve never seen in an adventure game, too. The quick time events are there, of course, but it goes beyond that. It’s pretty cool how an android will “pre-construct” a running, jumping, climbing route they need to take through a sketchy environment. They do this by projecting a wireframe construction of their actions onto the environment--testing this landing, pulling off that wall run, or making that leap of faith--then, once all the negative variables have been removed (that ladder is unstable, that jump is too far), then the android executes on the perfectly pre-constructed set of movements. It’s kind of brilliant. It works fantastically when Connor reconstructs a crime scene, too.

That jerk David Cage also put me in uncomfortable situations where I had a serious conflict of interest, more than once. Where two parties I had control of were given incompatible outcomes. That’s where the decision-making got very interesting. When I had to weigh the consequences involved with both parties, and orchestrate--to the best of my ability--having one particular outcome win out over another. It was phenomenal how I was being asked to improvise and adapt to a situation where I wanted both parties to achieve victory, but only to a degree, and I ultimately throw the fight for one of my characters. I don’t think I’ve ever been asked to do that in a game before.

I’m not going to sit here and tell you that every encounter was some all-new never-before-seen scenario. The mother figure android has a mother figure storyline. The black android has a black experience storyline. And the cop android has a hard-boiled detective storyline. The non-player characters you meet slip elegantly into familiar roles, too. There’s the gentle giant, the hooker with a heart of gold, the self-destructive detective, and so on. Character archetypes can be done well or done poorly. Some of them aren’t too bad here.

The subject matter is all relevant. It’s about the erosion--or at least the evolution--of the traditional nuclear family unit. About creating rather than replicating, especially when it comes to art and storytelling. It’s about the immigrant experience, the black experience, and where white privilege begins and ends. It’s about tearing down walls, whether personal, political, or societal. Detroit: Become Human is kind of fun throughout, so don’t let those Big Huge Ideas weigh you down. First and foremost, the game is an entertaining piece of software. If you don’t necessarily sit down on the couch with a gamepad in one hand and a newspaper in the other, trying to see which parts of Become Human were ripped from the headlines and which parts were lifted from domestic life, the game itself is still just a good time.

Become Human examines the strength and frailty of androids, which ultimately reflects the strength and frailty of the humans that invented androids. Androids are supposed to be a reflection of our best selves, when it comes to handling the menial tasks in life, anyway. But the game eventually questions that premise with a gripping little story. Thankfully, it’s also a story with the decency to leave a few questions unanswered. A few moments dovetail awkwardly, and David Cage doesn’t hold your hand through every loose end. I happen to love entertainment that leaves a little bit open for discussion or interpretation.

Markus’ story of demonstration and revolution is cradled with art and music. Connor’s story of law and order is punctured with sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Kara’s story of domesticity and maternalism is stricken with inclement weather and body horror. All three of them have stiff, robotic beginnings, and share an uncertain, destabilizing future. And while freedom and slavery mark every one of their android existences, their stories take widely branching paths. It’s a compelling adventure that lets you guide each character to either embrace or bury their emerging consciousness.

This is a transhumanism story for the android set. I devoured every chapter of these artificial intelligences shedding their artifice. And I learned that being human is filled with daily acts of self-sacrifice.

Rating: 8.5 Very Good

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile