Gorogoa

Sometimes the best games arrive on the scene not with an explosion of fanfare and convention confetti, but rather with a quiet wave and gentle smile before immediately settling down on the nearest couch. So comes Gorogoa, a hand-drawn puzzle game designed by Jason Roberts and published by Annapurna Interactive (the same people who published What Remains of Edith Finch, as a matter of fact). I have never before seen a game that is as clearly a labor a love as Gorogoa is. The game defies description, transcending the boundaries of both linear plot and artistic convention. Quite literally, it makes very little sense—but this is one of the very few situations where that’s a great thing.

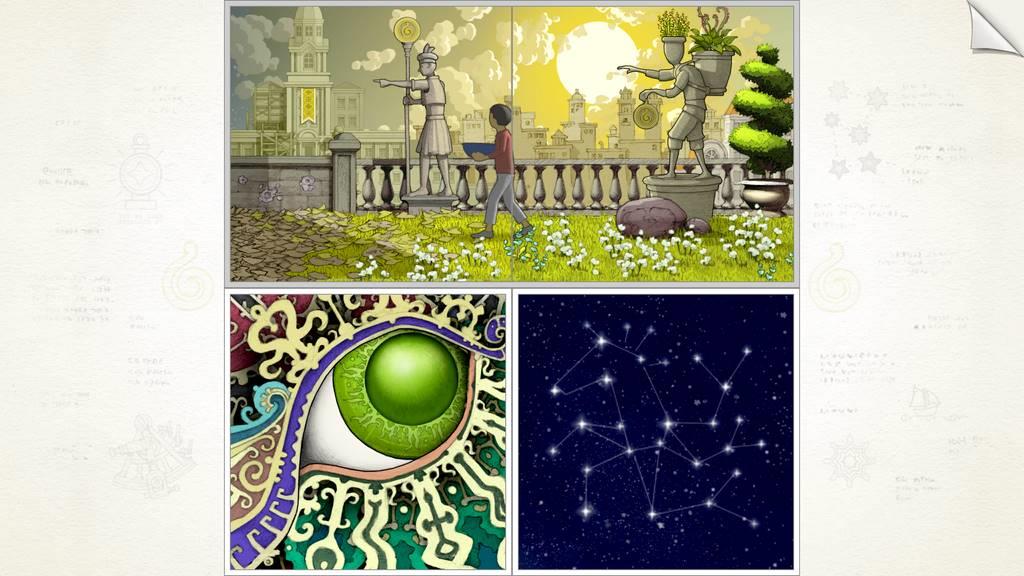

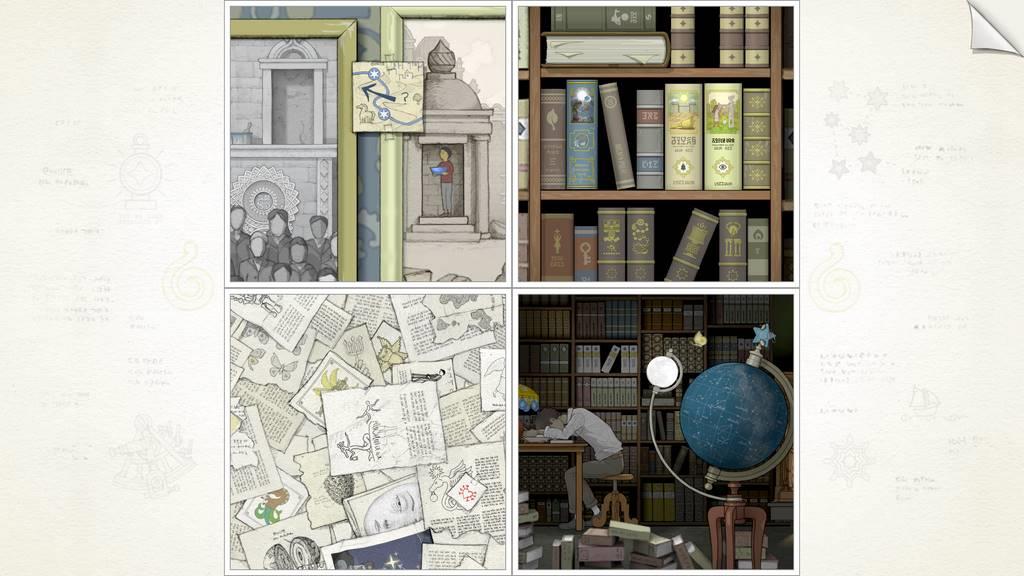

In theory, it sounds like a recipe for disaster. It’s a short, hand-drawn game with no dialogue and no instructions whatsoever aside from subtle hints as to what exactly you can click. You open on some sort of monster just visible between the buildings of a city (reminiscent of some parts of Italy, in a sense) and a child watching it. The story, as well as your objective, is told through pictures. The entire game takes place within four tiles, and you can click and drag each frame around to rearrange them within the four tiles. You can also dissect some frames, a few of which are partially transparent, in order to rearrange and overlap images to solve the puzzle. Oh yeah, and the movable parts of the game don’t really care much for “physics” and all that jazz; they’ll go in one door and out another, use stairs in Frame B to walk from Frame A to Frame C, or put stars in lanterns because point-of-view says they can.

Confused yet? It’s okay. Like I said, Gorogoa defies description. You just have to trust it.

In reality, it’s nowhere near a disaster. Everything has just the right balance. It’s not a long game—you can knock it out in a couple hours if you’re really going for a single sitting—but that doesn’t feel like a fault. Though it doesn’t make much sense spatially, the game eases you into how everything works with a gentle hand. Once you’ve got the hang of how things work—and have more or less accepted that in this world, everyone is okay with the laws of nature not really existing—then it gets harder, but never to the point where it’s unenjoyably frustrating. You fairly quickly get a sense for what you can drag and what you can’t, what you can overlap and what you can’t, and so on. It’s daunting if you look at, say, someone else’s terrible description of the game; you’ll likely wonder how on earth something like this could ever make sense. But don’t worry about it. Don’t trust me. Trust Gorogoa.

The puzzles are largely point-of-view based. If you need to light a lantern, overlap two images so a star is inside the bulb. If you need to break glass to let a moth fly free, let some rocks fall from one frame (a poor artist’s bedroom) into another frame (a rich scientist’s study) when in reality the two locations are nowhere near each other. If you need to move the child (who is the main player in this wordless story, though we sway from them often) then arrange two frames so they connect and form one image, and they will cross over. Realistically, the solutions make no sense, and they are never explained. But I can’t emphasize enough that they work because the game commits to them.

It’s difficult to describe, but I suppose that one of the main reasons why the game works overall is the sense that you’ve been set free. From the very beginning, when you are given no control menu or guide and must figure it out for yourself, you feel as if you’re being left to your own devices. You feel as though you must figure out your quest yourself (though they don’t make it difficult for you to figure it out, you still get that sense of satisfaction. Even the puzzles themselves help you transcend the drawn line, traveling in any way but linear—but, somehow, still making sense. Of course, the game only progresses when you do the thing that it intended, but that sense of restriction isn’t really there despite the fact that there’s only one solution to each puzzle. It really is oddly freeing.

To close, I’d like to bring my fiancée into the picture. I inducted her into the world of video games years ago, and she usually peeks in on the games I’m reviewing with mild interest because she simply has different preferences. While I booted up Gorogoa, she puttered around for a while before coming to rest behind me, saying she just wanted to sit with me for a moment—and then ended up sitting there in rapture for the entire duration of the game, with periodic exclamations and comments on how the game was just that cool. She wasn’t even playing it. Even as a spectator, she was ensnared by its design, by its stylistic art, and by its wholly unique puzzles, which is truly a special reaction for a game to evoke.

There’s not much more to say about Gorogoa for a few reasons: because it’s overall a pretty short game, and because it’s mostly an indescribable experience—meant to be played rather than outlined in a review. Reducing it to words when it so pointedly has none just twists the game into something that sounds nonsensical and confusing. To be fair, something this abstract isn’t always easy to follow. Gorogoa, however, masterfully makes you feel like you’re doing all this by yourself, even despite its restrictions. I’ve never felt free in a puzzle game of this sort before, and I’ve certainly never enjoyed one this much. Even reducing it to the term “puzzle game” feels like a disservice. It’s, as I said, a labor of love, and one that has excellence tucked into every corner.

Gorogoa is a relaxing, intriguing puzzle game that is a must-have addition to anyone’s game library. With unique art and unique gameplay, it’s a fresh new take on the genre, and its quality reflects the fact that it took years to perfect.

Rating: 9.5 Excellent

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been involved with games since I was a little kid, when I would watch my father play World of Warcraft for hours—and later, of course, mooch off of his account. I have a cobblestone background of creative writing, newspaper journalism, and multi-platform gaming, and I intend to add more stones to that mix as I get them. Excluding sports, I'm a fairly versatile player and will play whatever I can find, though I have a soft spot for lore-intensive games and fantasy. Personal interests include the interplay between history and video games, especially with games that contain archaeological elements—however fantastical—such as Horizon Zero Dawn and the Tomb Raider franchise.

View Profile