Thimbleweed Park

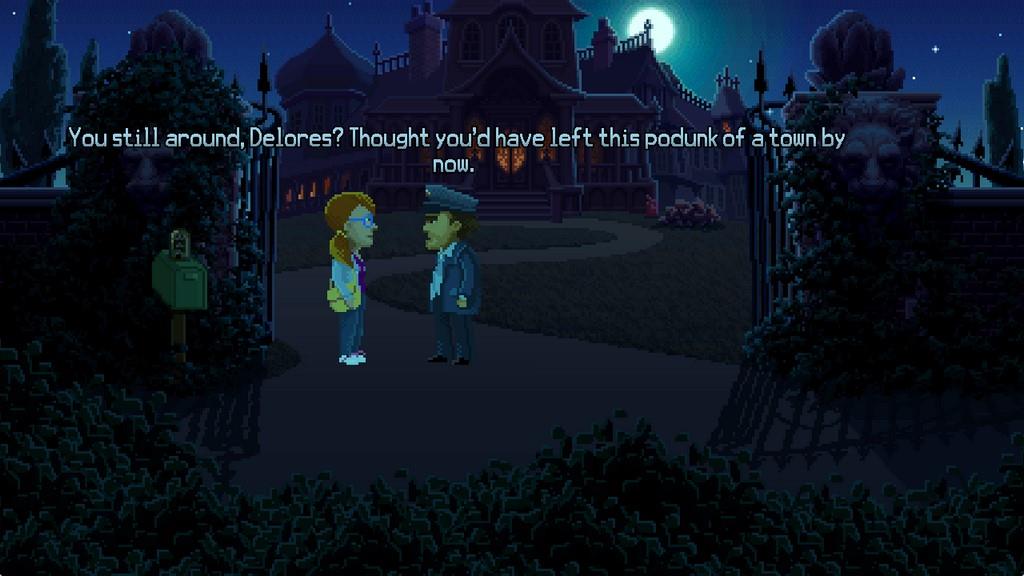

An 8-bit town with a Twin Peaks backdrop. A campy cast of bobblehead characters. A murder victim lying face down in the river.

Thimbleweed Park is the Kickstarted creation of Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, co-designers of classic point-and-click adventure games Maniac Mansion and The Secret of Monkey Island. I've played neither. Instead, in the 1980s, I was banging my face against Sierra On-Line adventure games like King's Quest and Space Quest. I don't know what inspired my "Quest" brand loyalty. I disliked those games, but didn't know any better.

Thimbleweed Park isn't borne of the Sierra On-Line body of work, as it's quick to point out in the occasional jab. It's borne of the Lucasfilm legacy. A legacy which Maniac Mansion basically crafted. Thimbleweed Park doesn't just "capture the spirit" of 1987's Maniac Mansion; it's not just a hat tip or even just a respectful homage to those early Lucasfilm games. Thimbleweed Park is meant to look, act, and play like some long lost 5.25-inch floppy disk you stumbled across in your old computer desk still at your parents' house. This isn't supposed to be a contribution to the 8-bit renaissance. It's made to be the real deal, stepping out of a Reagan-era time machine with steam trailing off its Air Jordans and a Stussy S drawn on a Pee-Chee folder.

I think Thimbleweed knocks it out of the park.

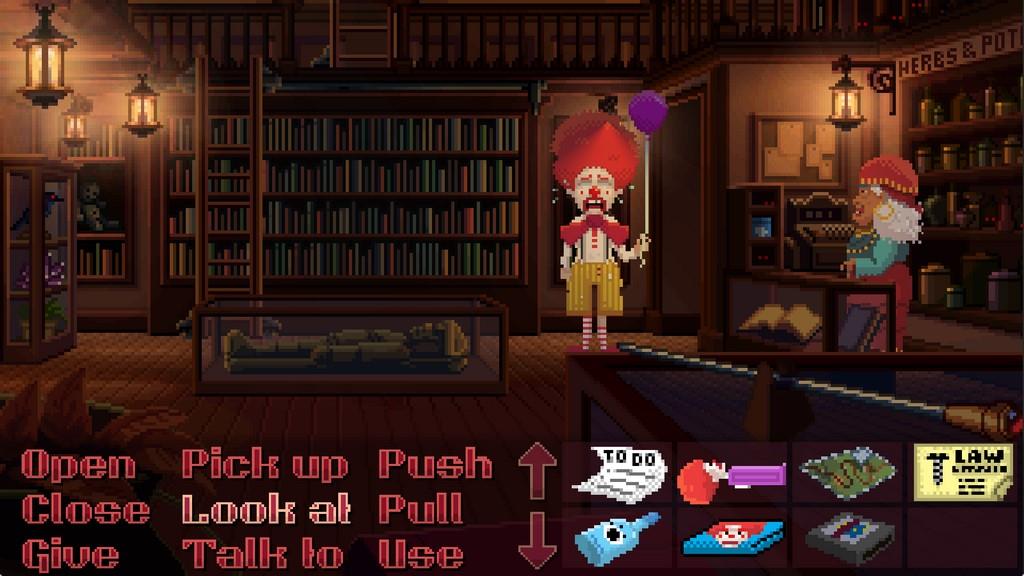

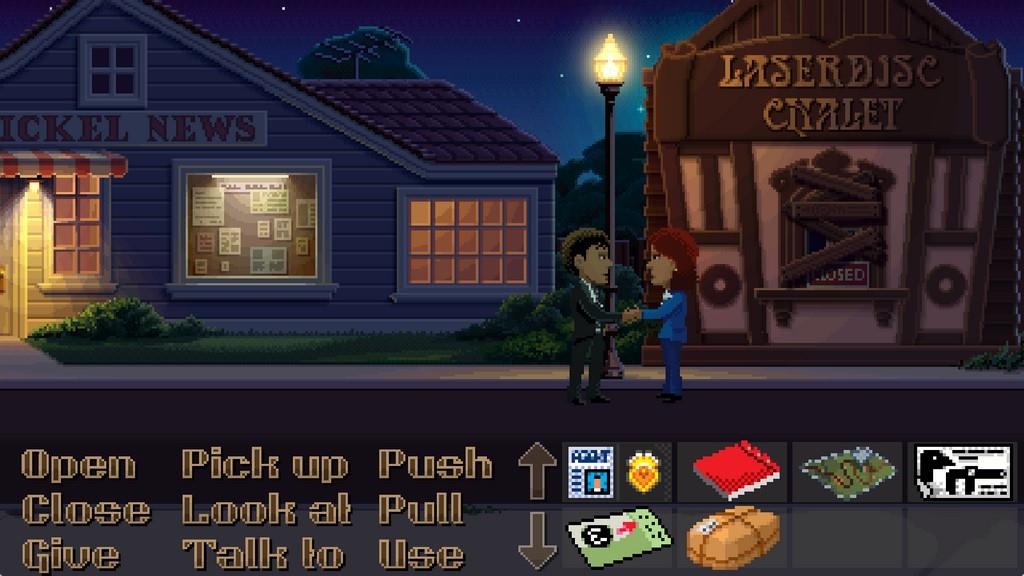

If you pull up side-by-side Google images of Thimbleweed Park and Maniac Mansion, you'll notice the family resemblance immediately. There's Ron Gilbert's verb-heavy actions and chunky inventory boxes in the lower half of the screen. There's Gary Winnick's flat scenery and big-headed art style. There's the quirky sense of humor digging its elbow into your ribs at all times. Rarely does this sense of humor resonate with me. But I got some chuckles out of everything. More than I expected.

In this murder mystery, you jump between the perspectives of five different characters. There are Angela Ray and Antonio Reyes, the two agents on the case, both with something to hide. There's Ransome the Clown, literally stuck in his own makeup, with enough "bleeps" in his language to fill up a cuss jar. There's Delores Edmund, heir apparent to the family's pillow factory empire, though she would rather hop the next bus out of town and go make video games. And then there's Franklin who wakes up dead in a hotel, though he doesn't know how he got there, although, no, he's not the same dead guy that Agents Ray and Reyes are investigating.

A slick, darkly jazzy noir theme song accompanies you around the town. You point and click items into your inventory. You point and click your way around the town caught in a perpetual dusk. You point and click through various geek-and-sundry references, through a mansion that is an almost pixel-by-pixel recreation of the Maniac Mansion itself, and through a set of appropriately cynical big-top tents and gypsy wagons. The click-the-verb-then-click-the-object gameplay is hamfisted nowadays, where contextual clues often turn your mouse pointer into exactly what it needs to be. But those verbs keep your action ruleset front of mind. You can "open," "close," and "give" stuff to the weed-smoking Keanu Reeves-alike at the minute mart. You can "pick up," "look at," and "talk to" the weird-a-reeno town sheriff. And you can "push," "pull," and "use" dozens of objects, from the agents' notebooks to the PrintTron 3000 vacuum-tube-driven printer in Delores's impeccably nerdy bedroom.

Yes, there are one-too-many clicks to be made, all in the name of throwback fidelity to the source material. But Thimbleweed Park also makes the concession that you can right-click the most basic functions you find on the screen. In other words, you can kick it old school by clicking on "open" and then clicking on a door, or you can simply right-click on the door and accomplish the exact same thing. Can't get through the game 100 percent this way, but mostly you can.

The environmental storytelling is rich. Aside from some lite inventory puzzles, the environmental puzzles cinch together the rest of the story. There's stuff every square inch contributing to the story, or to at least the character building. But your actions are often trivial. Making ink for a printer. Collecting specks of dust. Looking for a lost dime. Your moment to moment actions don't do much. But it culminates in a generally wacky, generally good time, as far as adventure games are concerned. Keep your sense of humor intact, though. Most of your interactions with the game world make perfect sense. But once in awhile they getcha, and make you play the age-old point-and-click metagame of "guess exactly what the developers want you to do next." Thimbleweed Park keeps its wits about itself. It doesn't go off half-cocked most of the time. Thankfully.

The character development, almost bar none, goes with the fish-out-of-water archetype. Everybody acts like a stranger in a strange land. The town's one newspaper reporter would've won a Pulitzer by now if the town wasn't so podunk. The former cake shop owner would still be making baked goods if selling vacuum tubes hadn't made her rich instead. Pigeon Bros. plumbing is owned and operated by two women. In full-body pigeon costumes. And those two might be the most comfortable in their own skin. I have no idea if "Pigeon Bros." is some kind of dig at the Mario Bros. and their extensive plumbing resumes. Some of these jokes are beyond me, but I'm okay with that. The hurr-hurr sense of humor stands on its own, for the most part.

Parts where it turns into "guess what the developers want you to do." Like when you're Ransome the Clown, and you need money out of a jar, and I had to click on so many different things that I can't remember what eventually got the money out of the jar. This is old school point-and-click at its most typical, and at it's most typically frustrating. When you see the solution but can't come up with the combination of button pushes to make it happen.

Thimbleweed Park adheres so faithfully to Maniac Mansion. At the same time, Thimbleweed Park runs the gamut of adventure game themes. It's a murder mystery, a police procedural, and a crooked buddy-cop episode; it's the tale of a tragic clown, loan-sharking carnies, and an improv stand-up comic routine gone awry; it's a tale of masking intentions, emoji-shrugworthy scapegoating, and an entire convention's worth of geek culture praising and punking.

There comes a point in every adventure game where it seems a walkthrough is your only hope. Thimbleweed Park gets there, too. The point where 50 percent of the spoken dialogue becomes, "Sorry, I can't do that," "I’m not going to do that," and, "That doesn’t seem to work." But the format is rather wide open compared to the often linear telling of the average point-and-clicker. The to-do lists that every character carries around—actual to-do lists with check marks and everything—is a blessing in disguise, though that doesn't make it seem needlessly overwhelming at times.

Thimbleweed Park proves how much adventure games have changed, and how they haven't changed much at all. You could say that about any genre, really. But the fact that Thimbleweed Park is almost instantly pick-up-and-playable is testament to the fact that Ron Gilbert's and Gary Winnick's fingerprints are still very much all over the point-and-click murder weapon.

Rating: 8 Good

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile