Torment: Tides of Numenera

With only a few introductory lines, my pupils practically dilate. Torment: Tides of Numenera, the thematic successor to 1999’s Planescape: Torment, is a dungeon-punk role-playing game with old school cRPG blood pumping through its veins. It lives and dies by its own mind-blowing concepts. It’s hard to imagine a more schizophrenic world since, well, since Planescape: Torment itself.

You are the Last Castoff of the Changing God. Hold on, let me back up.

Let’s talk about this Changing God first. There’s this guy, right? And he’s so thirsty for knowledge that he wants to learn everything. Only problem is, there’s too much to learn. More than anyone could learn in a lifetime. So this guy builds a path to immortality. He crafts a new body and then inhabits this new body. He lives a life in that body, and then, when that body has served its purpose, he builds another body to inhabit. He's effectively immortal. This is how he became the Changing God.

But the castoffs—the bodies he tosses aside—aren’t done. When the Changing God leaves behind a body, a new and entirely separate consciousness springs from within the castoff. And that’s where you come in. You are the Last Castoff. You know nothing of your life when the Changing God was in control. But now you’re a new person. Your own adventure begins today. And you wake up—falling from the sky.

If nothing else, it’s the most unique take on the good old “amnesiac protagonist” trope I’ve ever seen. You set off to learn about yourself as a Castoff, the Changing God, and your place in the world. You interact with people, places, and things, and by learning about the world around you, you learn more about yourself.

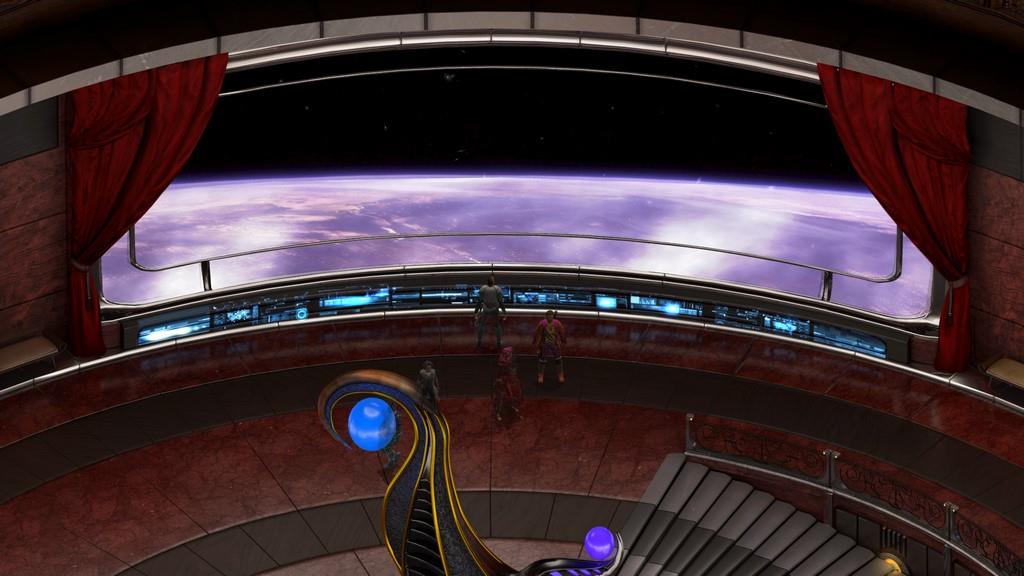

The world is crazy, though. It’s on Earth, but it’s one billion years in the future. Aside from (mostly) green grasses and (largely) blue oceans, very little is recognizable otherwise. You begin in the city of Sagus Cliffs. You see civilizations stacked on top of civilizations. Ancient buildings built atop futuristic buildings. Analog technologies colliding with digital religions. Magical tomes stacked beside tech manuals. You see people dressing in new-old ways, food prepared in old-new ways. One species builds a bridge to another race, and that race spans centuries to reach other past, present, and future species. It’s a trip.

You meet the Sorrow, your enemy, the enemy, that spreads more like an infection or a cancer than a demon or a swordsman. Your quest is to be hunted by the Sorrow until you step back into a resonance chamber where, you're told, everything will be fine once again. It’s a dull-sounding objective. I mean, think about it: You awaken, the Last Castoff of the Changing God, you’re prey for the Sorrow which hunts you to the ends of the earth and within your own mind, and you just want to rebuild your Hide-a-Bed and catch a little shuteye?

It’s all about the journey, however. Tides of Numenera is a world both beautiful and ugly, as baffling as it is logical, that wants to show itself to you, slowly, piece by piece, one weird cultural quirk, rite, and exhibition at a time.

Your first conversation already begins to affect the game's namesake tides. The tides are invisible, though you feel them constantly shifting. You can assume a certain posture in your tone and, in response, the Silver Tide might raise a tiny amount. There are five tides. To a certain degree, they serve like a character's alignment in Dungeons & Dragons (lawful good, chaotic evil, etc.). Yet, as the name suggests, these tides are a lot more fluid. But don't think about it too much. Play how you want and the tides will follow.

Rarely are your actions as black and white as, say, Mass Effect’s paragon vs. renegade system of morality. Many pivotal actions you take—or rather conversational decisions you make—will shift the tides in different directions. As you should expect from a game with complex scenarios, your decisions will pretty much never come down to “adopt the puppy or kick the puppy.” All of the tides seem to have positive and negative implications. It's just a matter what stance you take within these invisible tides. You can be compassionate; but is your compassion reserved for the citizens of Sagus Cliffs or the sentient creatures living beneath it? If you think it's an easy choice, just look at how social media responds to the death of a human, then look at how it responds to the death of an animal.

The game also floats on a million scripted words. A million. It has more words than the entire Harry Potter series put together. Talking points run up and down and interweave, rooting the gameplay in deep, rich, storytelling soil. If you aren't in the mood to read your video games (hey, I'm not always in the mood, either), or if you feel that video games are at their best when they say nothing at all, then look away. Tides of Numenera is not for you.

You'll be introduced to the game's entire premise: What does one life matter? I enter the city, and an execution platform stands adjacent to the main gate. A condemned man stands on the stage, seemingly coughing up his intestines, which twist around his body and slowly crush him. The audience is, in equal parts, excited, disgusted, elated, and numb. They all have their reasons. Some are here to memorize the words of a dying man. Some are here for entertainment value. Some want nothing more than justice. It's a disturbing one-man carnival of horrors, and it's impossible not to gather every opinion on the matter, to glean every excuse or justification for this act.

But what is one life worth? One life may be worth the bloody price of justice. One life could be worth “a trip across a long patch of ground.” One life is particularly meaningful to a slave owner, but a slave owner counts human lives as nothing more than cattle. The question pops up time and again.

I'm thankful for the game's visual minimalism. Reading about strange things is sometimes easier than watching them. Yes, the painted backdrops and architecture are crazy looking. But the spell effects and other visual disturbances are tame by most standards. Tides of Numenera, through entire novels' worth of text, requires more of your imagination than the average.

Your dialogue options (“What can you tell me about this place?”) are often dull (“What can you tell me about yourself?”) but the answers can be disturbing. The people you talk to say some weird stuff, and they often say it matter-of-factly. It’s amazing. Like Sigil in Planescape, Sagus Cliffs in Tides of Numenera is a city at a multicultural and multidimensional crossroads. It feels like any one or two lines of dialogue from any given NPC could spin off into another 80-hour adventure.

There's a certain torture in knowing all of that. The torture of knowing you’ll never have the time and energy to travel down each and every one of these storylines. There’s just no way. The stories are too big. The ideas are too big. I just met a supposedly “unremarkable” man named Malaise. I don’t think his name is a mistake. He tells you that he can be found in the tiny corners of the table, or in your bones when you shiver. These aren't his drunken, delusional ravings. Within the logic of the game, Malaise is being quite literal. It feels like I'll never know what I'm up against here.

Combat, however, is messy. Haphazard, even. Tides of Numenera is a story-first RPG. It's not an action-RPG. It's not made for hacking and slashing. Especially in narrow hallways, collision detection is the biggest enemy, with friend and foe alike, alive or dead, standing or lying in the way, making basic attacks thoroughly difficult to pull off, especially when the screen is swarming with a dozen enemies. The game loves throwing a dozen enemies at you at once, if you somehow fail to evade combat through conversation. Achieving line of sight is half the battle—and getting knocked down feels like it’s the other half. Corpses pile up and leave characters stuck. Some fights begin but the UI doesn’t shift into its proper “time to fight” mode. Corpses can float away and land someplace else. Combat in big spaces is okay, but it's awful in enclosed spaces. Again, combat is not the focus of Tides of Numenera, and it shows.

Not much in Tides of Numenera is ever expected. So much is wildly unexpected. There’s tons of pulpy, hard-bitten, expertly crafted writing here. You, the Last Castoff, more often than not, are often left with only a few open-ended questions to push your main quest forward, as seemingly trite as that quest sometimes feels. But that quest is fraught with wordy, well-written perils. The combat needs help. It's tougher than it should to be for a game that prides itself on non-combative resolutions. Other than that, Tides of Numenera has some of the most verbose world-building I’ve ever experienced in any game, but that's at the expense of experiencing any visually dazzling scenarios.

Like its spiritual predecessor, Tides of Numenera may achieve a modicum of cult classic status. It certainly deserves credit for pushing the envelope of traditional RPG storytelling. So, grab your reading glasses, put away your plain-vanilla reasoning, and see where the tide takes you.

Torment looks like a future-fantasy Lord of the Rings, plays like a collection of extreme short fiction, and emerges as the most alien world I've discovered in decades. Be ready for the narrative equivalent of combat fatigue. But if you’re in the mood for a complex world operating under a complex moral system, then it’s worth examining Numenera's overriding question: "What does one life matter?"

Rating: 8.8 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile