Fallout 4

The blue sky turned bland, and the sun faded behind a thick, green smog. I’d seen this kind of thing before. It was a radiation storm. Lightning snapped down in the distance but swirled closer to my location. The air howled with radiation from nuclear fallout, and the Geiger counter on my wrist-mounted Pip-Boy started crackling. An indicator popped up telling me that I was taking radiation poisoning from the weather. Visibility dropped to a hundred yards or so. I popped a couple Rad-X and put on my gas mask.

The Fallout series has been around since the 1990s. Based on its alternate-history, frozen-in-time, future Cold War setting, Fallout’s broken-down dieselpunk beauty has captured the hearts and minds of gamers for nearly 20 years.

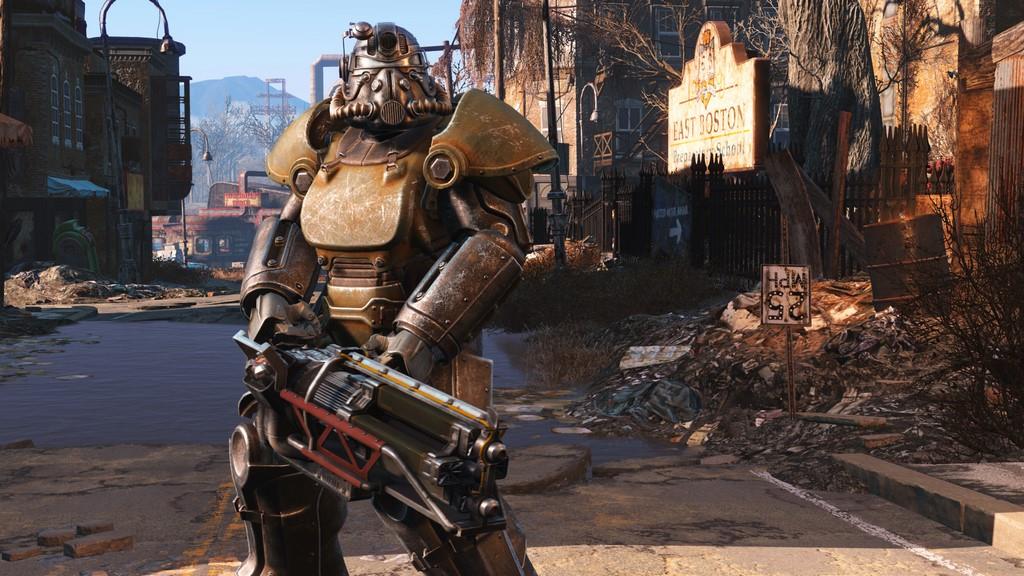

This time around, Fallout’s post-apocalyptic playground takes place in Boston. Welcome to the Commonwealth. Welcome to the Wasteland.

It was Fallout 3 in 2008, however, that handed the property over to developer Bethesda Softworks. From there, living legend game director Todd Howard and his team in Maryland applied their open-world formula—made famous by The Elder Scrolls series of role-playing games—and turned the Fallout series from a respectable classic into a global phenomenon.

Fallout 4 is a role-playing game. But stopping there in your description would qualify you for an "Understatement of the Year" award. There’s a layer cake 10 stories tall of interplaying game systems and mechanics that make up Fallout 4. Now, if you’ve ever played a game by Bethesda, then you’ve got a headstart on just how densely packed and nutrient-rich this game world is. Oh, there’s even more here, even if you’ve got hundreds of hours already invested in Bethesda’s library. If you’ve never played Fallout (or The Elder Scrolls, for that matter), then you’re about to have your mind blown.

You assume the role of a man or woman starting out in the Boston area, shortly before the bombs drop. Fallout has always been about family. Protecting it, preserving it, reuniting it. That principle, that drive, holds true here.

Some things are more than they seem. Other things can be taken at face value. But subversion, more often than not, is the name of the game. Tracking along the main storyline, the interplay between different factions gets complicated. Vault-Tec was going door to door, selling spots in underground shelters. But was Vault-Tec up to something more? The RobCo Corporation has its robots supplementing different roles in society, from manufacturing to social sciences, but is RobCo more than meets the eye? People are yelling about something called The Institute and how it’s the real enemy, but is it? Then you have traders walking the crumbled roads. The Brotherhood of Steel applying military order and martial law. A group called the Minutemen making a scrappy-underdog comeback on the scene. And raiders gonna raid, plundering the countryside, for reasons more complicated (or no more complicated) than you’d imagine.

Start drawing lines between these organizations, and it’s a tangled web it weaves. The series’ tagline is: “War...war never changes.” But between the sunny prelude and the blinding mushroom cloud, everything changes. And your character’s connecting thread between both of those worlds is more personal than it’s ever been.

The pulse-pounding opening chapters kick things off further with two of the most iconic creatures from Fallout: Rad Roaches and Deathclaws. The former, Rad Roaches, are the most ubiquitous of creatures and the most indicative of hello-you’re-in-the-post-apocalypse now. Remember how cockroaches are supposed to outlive us all? Well, they do, and they’re bigger now. And the latter, Deathclaws, are the top of the food chain, the dragons of this hellish world. When you see one, you’re going to get acquainted real quick with backpedaling and the sprint button.

Newest to Fallout is scavenging, scrapping, modding, and building. I strolled around my neighborhood for hours, collecting metal and wood, like some Jawa-minded Mr. Rogers. Will you be using your old mailbox, neighbor? No? Well thank you, neighbor. I’ll be working those building materials into my prefab metal-airplane hangar-looking two-story junkyard fortress just down the street. Yes, the one with automated turrets and floodlights on the roof, that one. Stop by sometime, neighbor. I’ll put another nickel in the nickelodeon and set out a plate of squirrel-on-a-stick with a Dirty Wastelander aperitif.

Things, indeed, have changed. It was difficult scrapping my old home’s rugs in order to recycle the cloth for new beds for a moody bunch of incoming refugees. But it had to be done. It’s a scary new world out there. Some memories will drive me forward. Some will hold me back. But old furniture held temporal, material memories that I had to let go.

Other relics of the past were, and still are, hard scrap. Like those mailboxes. Heck no, the postal service doesn’t exist anymore. But it harkens back to a time before the bombs. So, for the most part, the mailboxes stay, for me. Same with the street lamps. Are they going to put out any more light? Nope. The power grid has been down for who knows how long. But the street lamps stay.

No character you meet is the spitting image of anyone in Hollywood. But the leader of the Brotherhood of Steel sounds like a stoic George Clooney. The guy handling gate security at Diamond City has Bruce Willis’s squinty eyes and crooked mouth. And Piper from the newspaper not only sounds like Sandra Bullock, but she’s got a healthy fascination with an individual (you) that was cryogenically frozen for a long, long time, a la Demolition Man.

The voice acting stepped way up from previous Bethesda games. It was okay in the early 2000s to use the same five voice actors for a hundred non-player characters. But that’s less okay now. So, Fallout 4 has a ton more voice actors. Combined with gently animated conversation—simply by shifting back and forth on their feet or gesturing reasonably with their hands—there’s a lot more life in all of these characters than in previous Bethesda RPGs.

I’ve run into more white-knuckled encounters than I care to count. I ran scared to death as my first Deathclaw juked left and right, dodging my minigun fire, trying to tear the head right off my powered armor suit. You can thank Bethesda Software’s sister company, iD (makers of Doom), for help with the gunplay.

For virtually every mission, there are multiple approaches, multiple routes, multiple strategies. And countless outcomes. Do I hack the RobCo security unit to clean up these bandits? Do I log into a terminal and shut down the turrets and spotlights? Do I go in guns (and mind) blazing, addled on Psycho Jet and vodka? You’ve got options.

The storyline and side quests are very good at pointing you towards different locations on your map. Find this person. Recon that area. Clear out this feral ghoul hole. Stop those raider attacks.

It’s the stuff happening off the grid, off the beaten path, though, that goes a long ways in world building. There are small scenarios built into the environment, wherever you go. Like a skeleton in a wheelchair, holding a push broom, dying doing the only job that particular janitor could do, even into disability. Or the irradiated barrels tucked into a dark corner, away from inspectors’ prying eyes, in an otherwise bright and well-kempt factory. Or the raider camp that had somebody so hyped up on meds, they were seemingly putting Mentats and Buffout in their breakfast cereal; oh, and piling up people on a bonfire in the middle of a hospital. Across every acre of the map, there are dozens of these unspoken stories, painstakingly placed. There are generations of people’s lives, fighting faction’s takeovers, and general mayhem crisscrossing in a busted-up narrative tapestry.

And yet, there are times when you run across an inexplicable oasis of civility. No one’s around, perhaps (who knows where this madness has taken them), but there might be rich furniture in a solid arrangement around tasteful table settings and eye-pleasing decor. Right there on a street with feral ghouls pacing around, and heads, decapitated, chained up and burning like torch sconces just a few yards away. The urban and rural districts of Boston are dangerous. You have to take the good with the bad, even in an oasis.

In your travels, there’s so much junk to gather, scrap, and recycle in this survivalist dreamland. More than ever, Fallout is a game of encumbrance. I remember many cold mornings when I’d gather up all my belongings and do the overburdened walk of shame back to my home base.

To merely hint at the extensive systems at play, let’s break down one example. Let’s just, say, take an empty bottle. In any previous Fallout, this empty bottle would have little to no use; nothing beyond lite setting and environmental storytelling. But here, this empty bottle is infused with a lot more purpose. Some of these following actions sound redundant, but they are all, in fact, distinct actions you can affect on this bottle.

You can: take it, steal it, pickpocket it from somebody, hold it, drop it, distract somebody with it, buy it, sell it, buy it back, or barter with it, store it, lock it up, break it down (into glass), use that glass to build a light bulb, so you can light up a living room, which increases your settlers’ happiness, while the light also diminishes an enemy’s sneaking ability, so you can spot them easier through the scope you built with the glass into your rifle, so you can shoot those invaders, which increases security in your settlement, which likewise makes your settlers happier.

So, imagine how many ways, on a programming level, that any of those actions could go wrong. That’s just one example, and it’s by no means all-inclusive, of the different gameplay mechanics at work. It’s a logistical nightmare. How Bethesda pulls it off is mind boggling. The fact that I’ve run into only minor graphical hitching, or slightly erratic character behavior, is a miracle of engineering.

But, with all that in mind, yes, small glitches can pop up from time to time. Once (and only once), I crashed to the PS4 desktop while quicksaving after a particularly involved armor-crafting session. The game booted right back up, and all my progress had, in fact, been saved. Whew.

Also, the game is an open world, but isn’t always able to keep up with the linear portions of its narrative. Like when I returned to Vault 111, weeks later, but it still behaved as though I was in the story’s opening minutes (“Can’t wait around now,” my character said to himself again. “I have to keep moving”). Or when I got ahead of myself and started building out parts of my first settlement before the tutorial had asked me to. The tutorial would tell me to build something that I’d already built; so I’d have to remove it and replace it, and then the game would be like, Oh, good job, Randy, you did exactly what I asked. Or, just like in other Bethesda games, going through doors at the same time as NPCs can go awry. A couple times I turned on a radio and no music came out when it was supposed to. Occasionally, my companion sprinted around like crazy, trying to link back up with me, when I’d gone jumping around the environment, breaking our connection. No problem; my companion teleported back to my side a few seconds later.

Fallout 4 isn’t a horror game, but fight off some feral ghouls under a blanket of mist and a weak half-moon and act like that ain’t creepy. Fallout 4 isn’t steampunk, but don’t tell that to the pipe-armored raider rocking a bowler hat and a barbed-wire cane. Fallout 4 isn’t noir either, but the only person that can help me find a missing person...just became a missing persons case himself. And Fallout 4 isn’t a romance novel, but the first woman to meaningfully walk into my dude’s life sat down and shared her love of copyediting under the canopy of a noodle bowl restaurant. Maybe that’s not your kind of romance. It’s certainly mine. But Fallout 4 isn’t any one thing. It’s a lot of things, all of them done well.

The post-apocalypse is alive and well. Your reason for traversing Boston's mean streets, your relationships building along the way, and the mark you leave upon the Wasteland has never felt more meaningful. The rebuilding of society, and your imprint on its progress, creates a wonderful connection between you and the world after the fall. Fallout 4 lets you shoot stuff, loot stuff, and blow stuff up. But then it lets you rebuild, and that's when you'll feel the pulse of the Wasteland like you've never felt it before.

Fallout 3 was seven years ago. Fallout 4 is one you can play, off and on, for the next seven. Congratulations, Bethesda: You’ve outdone yourselves again. You’ve made the Wasteland more beautiful, ugly, open ended, funneled down, thoughtful, and frantic than ever.

Rating: 9.8 Exquisite

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile