Alien: Isolation

I’ve been an Alien fan for longer than I can remember. Even before I could understand it, even when I was a little kid and my folks wouldn’t let me watch the movies, I was obsessed. I saved my allowance for all the old Kenner toys, I read the Dark Horse comics and I sketched aliens in my notebooks at school. Heck, my parents went to see the original 1979 film on their first date. You could say the Alien is in my DNA.

Of course, I also played the Alien games. And like a lot of fans, I realized that most of the games didn’t get it right. That’s not to say they were all bad—many of them were pretty good—but were they scary? To be honest, the only Alien game that legitimately scared me was Rebellion’s Aliens vs. Predator in 1999. It was scary because it made you feel weak, desperate, and alone. Isolated.

Above all other reasons, that’s why Alien Isolation succeeds: it makes you feel alone and vulnerable. It takes a drastic approach to do it—robbing you of nearly all offensive options and throwing obstacle after obstacle in your way—but damn, does that core concept just work. You have little more than your wits to rely on as you confront the most dangerous enemy in the galaxy. Isolation succeeds in a lot of other areas too, and it really shows the dedication and skill of Creative Assembly. Isolation is one relentlessly pursued idea, supported by a stellar production on all sides.

Isolation picks up 15 years after Ellen Ripley destroyed the Nostromo and went missing near Zeta Reticuli. Her daughter Amanda has been working in that area, hoping to find a clue to her mother’s disappearance. She catches a break when Samuels, a Weyland-Yutani rep, offers her a chance to go to Sevastopol station. Supposedly, Sevastopol has retrieved the Nostromo’s black box. Naturally, when Amanda Ripley arrives things go south quickly, she is separated from her crewmates during an EVA and barely makes it onto Sevastopol. Once onboard she realizes things are much worse than she anticipated—the surviving station occupants have become paranoid and territorial, the station’s androids have gone bonkers and there is something terrible stalking the people left on Sevastopol.

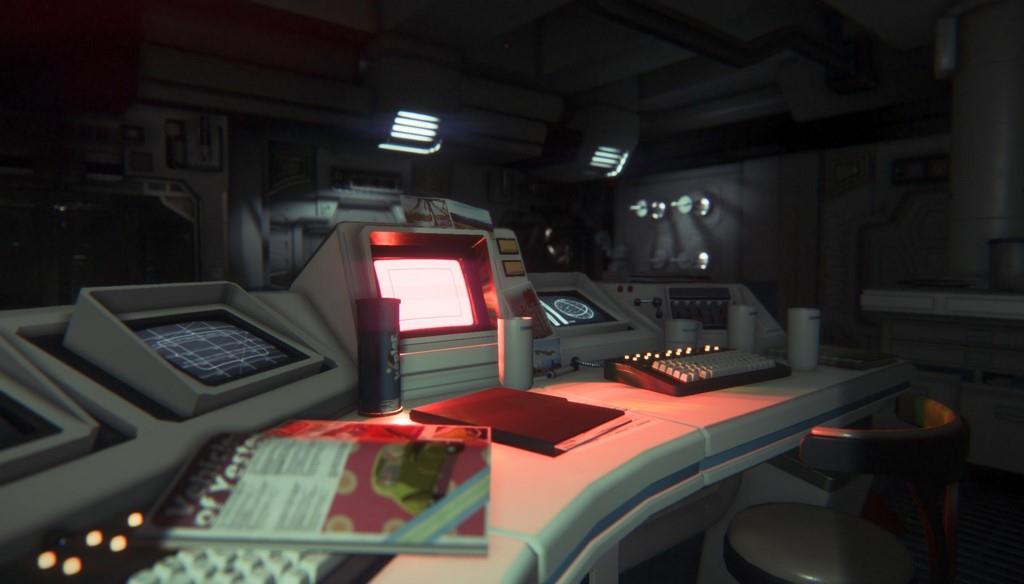

It’s clear that atmosphere was important to Creative Assembly because that’s the one aspect of the game they’ve gotten perfect. I’ve played maybe three other licensed games—one Star Trek, James Bond and Star Wars each—that got every last detail right, and Isolation is one of those kinds of games. Sevastopol and Nostromo must have been built by the same manufacturer because they are identical in design. Every sound effect, every texture and art asset right down to the buttons, padded cream-colored walls, and the vintage Tupperware coffee mugs are straight out of Ridley Scott’s movie. It’s a rare experience for a fan, to step into that world you’ve seen so often and committed to memory, and everything is exactly as you remember. It’s exhilarating and terrifying, and I’d love to hear what Ron Cobb, one of the groundbreaking artists on the original film, thinks of Isolation. It’s also too bad that Alien co-creator Dan O’Bannon isn’t still around to see Creative Assembly’s work.

So the atmosphere is perfect, but previous Alien games have gotten the details more or less right and still failed. Colonial Marines seemed obsessed with pulse rifles and space marine jargon but the game itself was a bore. Thankfully, Creative Assembly have delivered an Alien game that fulfills the concept of the original film: a true haunted house in space. Isolation is a survival horror game in the classic tradition, using tension, pacing, scarce resources and perpetual risk to drive the gameplay. The first couple hours are a slow boil, as you learn what happened to the station and internalize the basic mechanics through some very organic tutorials. In fact you don’t see the Alien at all for the first level or so; a brilliant suspense-building strategy previously employed by Aliens vs. Predator 2 and even the classic Aliens Total Conversion mod for Doom.

These early areas of Sevastopol reminded me of Dead Space and Bioshock, but they felt more natural and less “trying too hard,” probably because they weren’t emulating anything. I like Bioshock and Dead Space fine, but sometimes the original is just the best. Sevastopol is owned by the failing Seegson corporation, and everything they do is a cheap knockoff of Weyland-Yutani. You get the sense that things were already pretty desperate before the crisis on the station began, with some in-depth world-building that should be interesting for any Alien fan.

Of course once the Alien shows itself, all bets are off. The game introduces it so abruptly that you can’t help but get an adrenaline spike seeing the thing. The Alien is horribly beautiful to behold; Creative Assembly have recreated the disturbingly sexual contours and eerie, graceful movements of H.R. Giger’s original monster down to every glistening biomechanical detail. The way it unfurls from overhead ventshafts, methodically stalks and investigates rooms and then creeps out the door, its tail slithering languidly behind, never failed to send a shiver down my spine. It’s a shame that Giger and Bolaji Badejo, the Nigerian artist who portrayed the creature, aren’t alive to see it recreated with such dedication.

The Alien is terrifying because it is so dangerous, and Creative Assembly have made every element of the gameplay reinforce this fact. If the Alien sees you, you’re dead. Simple as that. You can’t outrun it—it’s too fast. You can’t hurt it—your small arms are too weak (remember, the pulse rifle fired explosive-tipped ammo in Aliens). You can distract it with cobbled-together noisemakers or flares, but this should be a last resort, as the Alien will learn your tactics over the course of the game. Once or twice a flare might send the creature scampering away like a hideous distracted puppy, but try that a third time and the Alien will just ignore it; it’s seen that trick before.

Even when you get Ripley’s iconic flamethrower about a third of the way into the game, this weapon is only a delaying tactic. The Alien can be scared off by a sustained burst of fire, but you’ll only buy yourself thirty seconds or so at best. You’d better hide, because when it comes back it will be pissed and looking for you. Hiding and avoiding conflict is almost always the best strategy, because—with only a few exceptions—the Alien is always with you.

You can hear it, creeping around in the vents above. Make too much noise and it will come down to investigate. This goes for the other trigger-happy human survivors as well. They’ll stupidly cap off a revolver at you which is basically ringing the dinner bell for the Alien, bringing its fury down upon them. In one level, I found a cabinet to cower in after inadvertently stumbling into a turf war. The humans were gunning for me, but their attention quickly turned to the Alien. I had no choice but to sit tight and listen as the creature slaughtered my attackers, praying that it didn’t find my hiding spot.

Creative Assembly smartly understands that sound is just as important as graphics, if not more so. What you don’t see is scarier than what you do, so you quickly learn to recognize the Alien’s signature slither as it enters and exits vents, its heavy footfall, its rattling hiss when it hears something, and that terrible scream that tells you death is seconds away. The soundtrack, a dynamically re-recorded and expanded version of Jerry Goldsmith’s original score, masterfully reinforces the perpetual terror. As the Alien stalks closer to your hiding place, those familiar shrill violins and off-tune horns get louder, more insistent and discordant. There are also reworked versions of music from early in the film, to set up a false sense of security in moments when you aren’t being hunted. The theme from the self-destruct sequence at the end of the movie is applied to desperate, panicked sequences in the game.

The motion tracker, probably Isolation’s most useful item, also underscores the importance of sound in the game’s design. It will let out an idle squawk whenever it picks up movement, and you’d best pay attention to it. Its fuzzy display only shows the Alien’s exact location when it’s in a narrow cone in front of you, providing only a vague indicator behind and to the sides of you. Limited as this tool is, it still saved my bacon many times throughout the game, but you have to be smart in using it—it doesn’t just pick up the Alien, but the aforementioned humans too, so you have to be aware of your surroundings.

Panicky humans are easy to deal with compared with the station’s creepy, implacable androids. Seegson’s “Working Joe” model synthetics aren’t nearly as smart or realistic as the Weyland-Yutani built Ash or Bishop, but what they lack in brains and looks they make up for in toughness. I got a real Westworld vibe from these guys—soulless, glowing eyes, identical jumpsuits and rubber crash dummy faces. A Joe can take a full cylinder of revolver slugs to his face before he will go down, and if the androids get their hands on Ripley they’ll beat her to a pulp. They don’t take kindly to you tampering with the station’s equipment, and later on they all go hostile. Killing one makes a lot of noise and brings the Alien running, but what’s even worse is that the creature ignores the androids entirely to focus on you—I guess they don’t taste very good?

The biggest element that sustains this level of fear is the game’s brilliantly rudimentary save system. There are no checkpoints, and the game only auto-saves at the very beginning of a new level. You must manually record your progress at save stations placed periodically around Sevastopol. You’ll quickly learn to seek out the soft, constant tone they emit, and you should also search for map terminals to pinpoint each save point’s location. Memorizing where the save stations are becomes your first priority when entering a new level, because if you die, you go all the way back to your last manual save. Haven’t saved in an hour? Too bad! This led me to develop an almost compulsive saving behavior; whenever I’d pass by one of the blinking phones, I’d pop in my access card and save, just to be sure. The phones will also warn you if there are enemies nearby, and –deviously—it takes three agonizing seconds for them to boot up. You can die at any time during those three seconds and you won’t have saved squat.

The save system didn’t frustrate me as much as it did some other reviewers, probably because it reminded me of the system in the Metroid Prime series and thus was kind of nostalgic. Then again, Samus never had to worry about a Space Pirate sticking a shiv in her side halfway through a save. You just get used to it, because the whole station is like that. Sevastopol is a wonderfully clunky, analog environment where every display is a staticy CRT monitor and every interface requires multiple button presses, clacky keystrokes and lever-pulls to operate.

To activate levers and switches you usually have to coordinate several mouse-and-keyboard inputs in tandem, emulating the action of yanking down a stubborn generator handle with both hands. The hacking minigame plays out on a blurry radio tuner reminiscent of an old green-screen Game Boy, and every SevastoLink ™ computer terminal seems to be running an archaic Seegson DOS ripoff. You even have to memorize (or write down) security codes for doors and supply lockers; the game doesn’t helpfully call them up when you find the door in question. It’s as if the whole station is obstinately refusing to make your life any easier—this is the 70’s era technology of an indifferent, user-unfriendly corporate world.

To some players this will be maddening. But for me it just recreated that dreary, passive-aggressive Alien universe all the more accurately. It also made Amanda Ripley a more capable and intelligent character, for being able to operate all of this obtuse equipment with the threat of horrible death constantly hanging over her head. She would make her mom proud, that’s for sure.

Some critics have said that the game is too long, that it wears out its welcome and the terror isn’t sustainable throughout the entire game’s 20-hour length. In some ways they’re right, but Isolation does take a break from hunting you about two-thirds of the way through, with an extended sequence where you fight and evade androids. Was this sequence a bit too long? Admittedly, yes. I’d even trim a level or two with the Alien, just to improve pacing. But was the game any less scary by the end? No way. There’s a white knuckle cat-and-mouse sequence through some burning corridors in the penultimate level that was just as tense as when I faced the Alien the first time. I was still scared, but by that time I had learned to control my fear and not panic. The fact that everything else was going wrong and every last system on the station refused to work only heightened the stress, it didn’t make me frustrated. And that brings me to my most important observation about this game.

Alien Isolation is not for everyone. I’ve seen several critics complain that it’s too long, or too difficult, or too frustrating. I can’t account for their taste but I think some of them might be missing the point. Isolation is supposed to be tense, risky and hard—the save stations, the Alien’s AI and the sense that the game is actively working against you all contribute to its perpetual sense of unease. Isolation doesn’t let up and it doesn’t pull punches, and that’s what makes it scary as hell. I played through the game on easy mode for the sake of getting this review out in a reasonable timeframe, and it still had me losing sleep and more or less depleted my adrenal glands after a week of constant play.

If you aren’t in the mood for a good, sustained scare, Isolation probably isn’t for you. Even if you think you’re up to the challenge, I have some suggestions. First, play the game on easy mode—the Alien gets exponentially more perceptive and devious as you ramp up the difficulty. Learning the layout of the station, the game mechanics and objectives can make subsequent playthroughs on medium or hard a lot less frustrating. Second, take frequent breaks, especially on your first run. Isolation can be mentally and physically exhausting, just like any great horror film, so put it down every few hours and go watch something funny or spend time with friends. Return to Sevastopol only when you feel recharged and confident; I guarantee you’ll have a lot more fun that way.

If you can brave the challenge, this game has some incredible, classic Alien moments. My favorite was early in the game, when I was making my way back out of an area where I’d set off an alarm and androids were hunting me. I could hear the Alien in the ceiling, so I was slowly crawling across the floor to the exit elevator. I saw what looked like water dripping onto the deck and though, “huh, I didn’t see that when I came in.” Then I looked up, and saw that the water was really drool pouring from a darkened ventshaft. It was there, waiting for me. I backed away, wedged myself as far as I could go into a corner, and waited for the Alien to move on. Isolation is full of sequences like these, completely unscripted, and all you need is the patience and perseverance to experience them.

Over the past few years I’ve seen several great horror series—Dead Space, Resident Evil, Aliens—turn into little more than cumbersome shooters and action games. No doubt this comes from misguided publishers, who think Call of Duty and Gears of War are the only things making money. The result is a series of so-called horror games that at best aren’t scary, and at worst are downright boring. This shortsightedness has left an entire audience unserved and craving a good scare. To fill the void, a new generation of indie developers began providing games like Amnesia, Outlast, and Slender.

A lot of people are saying Creative Assembly took a big risk by making a hard, pure horror game and marketing it to the mainstream. Personally, I think Creative Assembly knew exactly what they were doing, because they know their audience very well. Alien fans have been screaming for this game for years, and those who can truly appreciate what Alien Isolation is will make this game a classic. It’s a very different kind of Alien game, and I hesitate to call it the very best because it’s really in a class of its own. I still love Rebellion’s Aliens vs. Predator, but it really can’t be compared to Isolation; I love them both because each one gives me something very different.

In conclusion, let me put it this way. In my many years as a gamer, I’ve played all manner of horror games, from schlocky pabulum like Resident Evil 6 to bone-chilling classics like Eternal Darkness. As far as I can recall, Alien Isolation is the first game to have actually given me nightmares.

Masterfully crafted and relentlessly terrifying, Alien Isolation is a lean horror experience that focuses on a few strong core elements and supports them with stellar production values. Aside from a few pacing issues, it's a tour-de-force that no Alien fan should miss. It may be too punishing for some players to enjoy, but no Alien game has captured the dread, suspense and atmosphere of the original 1979 film the way Isolation has.

Rating: 9 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been gaming off and on since I was about three, starting with Star Raiders on the Atari 800 computer. As a kid I played mostly on PC--Doom, Duke Nukem, Dark Forces--but enjoyed the 16-bit console wars vicariously during sleepovers and hangouts with my school friends. In 1997 GoldenEye 007 and the N64 brought me back into the console scene and I've played and owned a wide variety of platforms since, although I still have an affection for Nintendo and Sega.

I started writing for Gaming Nexus back in mid-2005, right before the 7th console generation hit. Since then I've focused mostly on the PC and Nintendo scenes but I also play regularly on Sony and Microsoft consoles. My favorite series include Metroid, Deus Ex, Zelda, Metal Gear and Far Cry. I'm also something of an amateur retro collector. I currently live in Westerville, Ohio with my wife and our cat, who sits so close to the TV I'd swear she loves Zelda more than we do. We are expecting our first child, who will receive a thorough education in the classics.

View Profile