The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds

I like The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past just fine. It still stands as one of the best games of all time, and a groundbreaking achievement in the action adventure genre. I freely admit that a lot of my fondness for the game is also nostalgia. I spent a lot of time commuting to and from OSU campus during my college days, and I sunk hours into the Game Boy Advance port while riding that COTA bus. I will always appreciate Link to the Past for both its historic and personal significance; that said, it’s not my favorite Zelda game.

It’s not even close to the top of my list, actually. Sure, I like it better than Wind Waker, Phantom Hourglass and Spirit Tracks combined, but I still like Ocarina of Time, Majora’s Mask, Twilight Princess, Skyward Sword and even Link’s Awakening more. My reason is pretty pragmatic: I consider all of those games to be better than Link to the Past, and that’s not a bad thing. Link to the Past established the foundation for every Zelda game since, so as solid and elaborate a game as it is, it still has some rough edges. I’ve often wondered how Nintendo could update that SNES classic with some of the ideas and innovations they’ve come up with since. I don’t have to wonder anymore.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds answers all those speculations. It is at once nostalgic and new, Nintendo’s attempt to pay homage to the series’ roots while infusing it with new concepts. The fact that it works very, very well and is such a massive game is pretty amazing too. I’ve been playing this game full tilt for over a week, and I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface. It’s hard to put into words, but A Link Between Worlds feels like playing A Link to the Past over again, but new; that same head-snapping sense of scale, the slowly dawning realization that gaming has just changed forever.

The game takes place a couple centuries after Link to the Past so there are plenty of references and narrative callbacks to that game. In fact the overworld map is largely the same; there are a number of changes to show that time has passed (and to keep the gameplay fresh) but you’ll get a serious sense of déjà vu the first time you boot up the game. Link begins the adventure as a simple blacksmith’s apprentice, but after a chance encounter with the vain new villain Yuga, Link’s sword delivery errand turns into a full-on quest to save Hyrule.

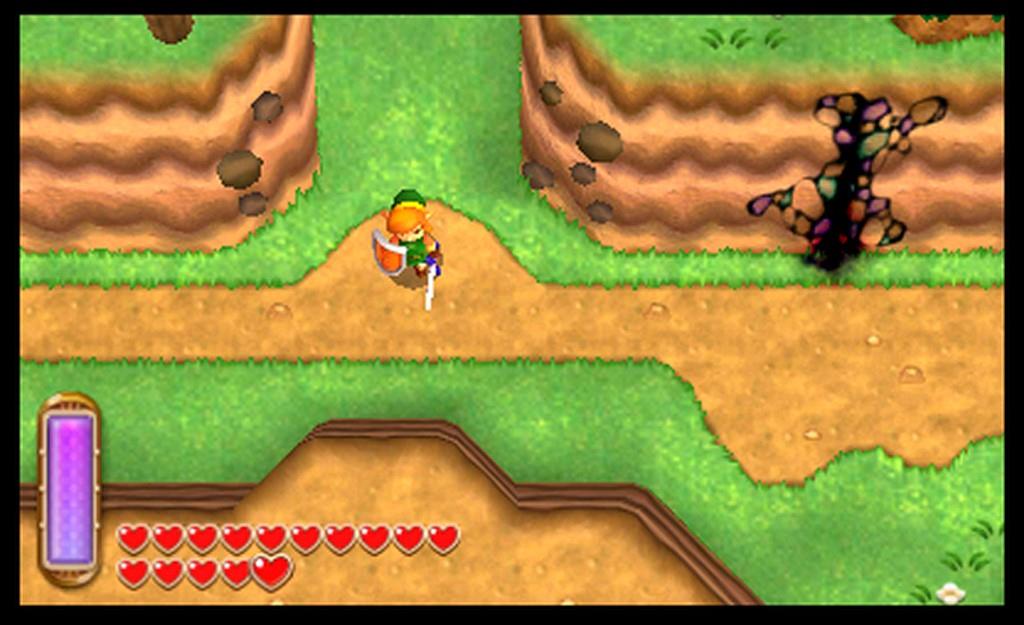

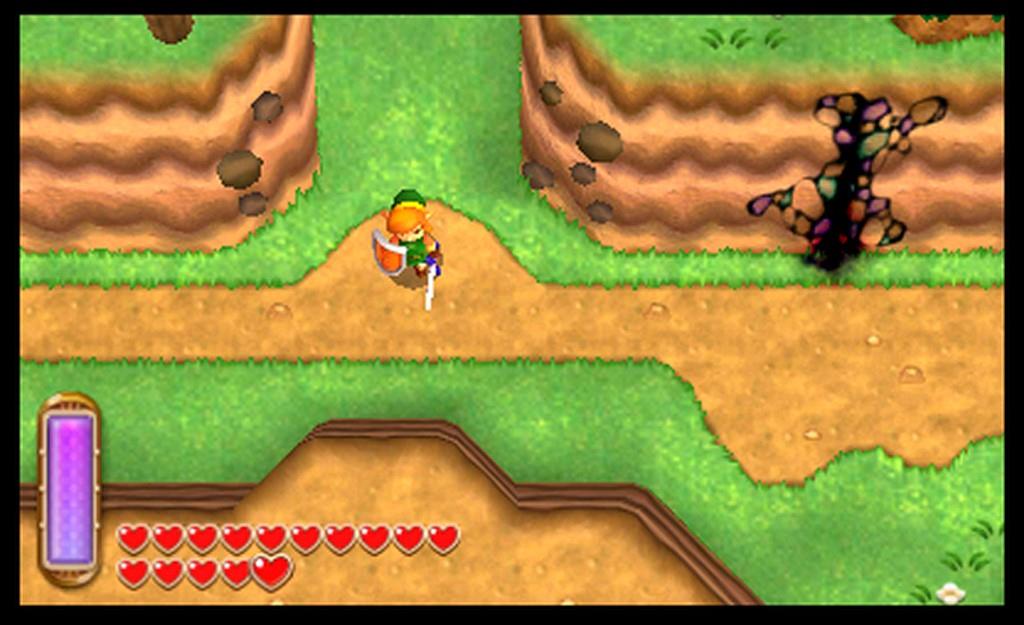

Yuga is running around the kingdom turning people into paintings with his magic scepter. He seems to be “collecting” certain people while leaving others—castle guards, average citizens—pasted on walls. When Link crosses his path one time too many, Yuga leaves Link hanging as a doodle on a dungeon wall, but thanks to an old bracelet Link borrowed from a friend, he doesn’t spend the rest of the game as immobile watercolor. Instead, the bracelet gives Link the ability to turn into a living portrait at will; he can slip onto any flat, vertical surface and “walk” back and forth laterally, so long as his energy meter holds out.

This new mechanic is the central concept for the entire game. It’s not a gimmick—as soon as you gain this ability, you’ll be putting it into use extensively, in dungeons and on the overworld. Certain obstacles can impede your movement across a wall, like a crack, missing bricks or a partition, and you can only move left-to-right, not up and down. This makes for some incredibly creative environment puzzles and turns many rooms into impromptu brain-teasers. The ability is used in every dungeon after you acquire it early in the game, but is also quite handy to have on the overworld; on several occasions I was stumped on how to get to a treasure chest or piece of heart, and suddenly remembered “hey, I can stick to that wall!”

This painting mechanic is so integral to the game, so seamlessly integrated and the puzzles so well designed, that in my opinion it ranks up there with Portal. It really does make you rethink the way you play Zelda games.

The other big game-changer is an idea the Zelda series hasn’t played around with much since the very first game on the NES: namely, the ability to tackle dungeons in any order. Early in the game an enterprising wandering merchant named Ravio sets up shop in Link’s house. He soon begins renting the Zelda series’ signature tools of the trade: boomerang, hookshot, bombs, hammer, etcetera. As long as you have enough money you can rent virtually all the items in the game from Ravio simultaneously, so with a few exceptions you can solve any puzzle or dungeon in the game. The catch is that if you die and restart from a checkpoint, Ravio retrieves all of his items and you have to rent them again. Sometime later you have the option of outright buying the tools so you never lose them, but the price is considerably steeper: 50 rupees to rent, 800 to buy.

Each dungeon has panels on the floor, engraved with the items needed to solve that particular room or puzzle. You often don’t need more than a couple at a time, so it’s very helpful that the game spells out exactly what you need instead of making you guess. This can be welcome toward the beginning of the game when you’re low on funds and renting all of your tools, but once you get past the third dungeon or so you should have enough rupees to permanently purchase your most-used items.

A Link Between Worlds also has a unified checkpoint and fast-travel system, very similar (but thankfully more efficient) to the one in Skyward Sword. There are several weathervane statues scattered throughout the overworld (curiously shaped like birds…) where you can save your progress. Early on Link makes friends with a sarcastic young witch-in-training named Irene, and due to a prophesy she feels obligated to help you by ferrying you back and forth between checkpoints on her magic broom. This makes navigating the world much easier than in past Zelda games and cuts down on needless backtracking.

All in all, I’d be very happy to see these improved mechanics—item renting, fast-travel, and even the painting ability—integrated into future Zelda games. To be frank, they make the Zelda formula a lot easier to play around with, and in general the game is less of a hassle. It’s kind of like when I first played a Saints Row game, and realized the GTA series was getting away with a lot of lazy gameplay structure and pacing problems that should’ve been fixed ages ago. The game’s director, Eiji Aonumas said that A Link Between Worlds was a test bed, a way to refine old ideas and introduce new ones to the series, and he also said he’s been inspired by games like Skyrim. It’s good to see that the Zelda team isn’t above emulating good game design, especially when it’s something they didn’t necessarily come up with.

Of course this wouldn’t be an official sequel to Link to the Past without a dark world. In this new game the dark world is given the name Lorule, and this time it’s more like a shadowy parallel universe with mirror images of all the characters from the normal world. In some ways it’s a lot like Termina in Majora’s Mask; in fact there are numerous references to that game throughout A Link Between Worlds. Link even has the horrifyingly malevolent mask hanging on a wall in his house, for what reason I have no idea. Hopefully it is merely a hint that Nintendo has heard fans’ pleas, and are working on a 3DS remake of the game to go along with Ocarina of Time 3D.

Regardless of nostalgic callbacks, getting into Lorule is a lot easier than it used to be. Instead of the portal-on-floor, moon-pearl, magic-mirror song and dance you had to do in Link to the Past, now Link can slip between literal cracks between worlds. The transition is fast and seamless, broken only by a small (and somewhat unsettling) cutscene, and then you’re back in action. You don’t have to retrace your steps to an old portal or leave a temporary one hanging there with a mirror; it’s as simple as finding a crack and shimmying through. This makes dimensional puzzle solving a lot more straightforward and really opens up some clever uses of the painting mechanic. In short, you’ll be putting your intellect toward solving a puzzle, not wracking your brains on how to get from one dimension to the other.

Lorule itself feels more balanced and natural than the dark world from Link to the Past, and this factors into the new game’s robust but fair difficulty curve. If you were dreading another ostensibly easy (but padded and tedious) Zelda game like Phantom Hourglass, relax. The new game’s difficulty starts off reasonably brisk and gradually ramps up from there, adjusting remarkably well to the new ability to rent items. It’s similar to Skyward Sword’s difficulty model: the game is surprisingly difficult to start off and stays challenging throughout, but you can feel yourself getting stronger and more capable as you gain new abilities and items.

This is a welcome change from Wind Waker, where only the creative dungeons saved the gameplay from getting really, really easy and repetitive. Compared to its predecessor, A Link Between Worlds is both reminiscent of and more fair than Link to the Past. Lorule’s stronger, more numerous monsters will keep you on your toes, but you won’t be constantly, desperately searching for a way back to the normal world. Also, it is once again a very good idea to keep a few fairies stowed in bottles for the game’s bosses.

Nintendo has pulled out all the stops for A Link Between Worlds’ production values, and in a lot of ways it feels like a console release rather than a handheld game. Calling it gorgeous would be an oversimplification. The art style, while in some ways just a little too cute for my tastes, looks like the realization of Link to the Past’s original concept and advertising art. Nintendo accomplishes this through highly expressive character design, and the subtle application of shaders on nearly every surface and object in the game. It doesn’t beat you over the head with shaders like a lot of games these days; rather, it’s the little details that sneak up on you. I’d be chugging along, exploring a new area, and notice the delicate sheen on a wet stone wall, or the gentle texture mapping on the grass in a field, or the texture of the carpet inside a temple. After years of stalwartly resisting HD resolutions and pixel shaders, I think Nintendo has finally found a comfortable balance between art and technology in their visuals.

Nintendo is also continuing their stellar track record in orchestral music. Nearly every piece of music in the game, from the smallest fanfare to the triumphant new rendition of the classic overworld theme, has been recorded by a live orchestra and it is spectacular. Nintendo seems to have realized that fans really like Koji Kondo’s Zelda music, and Nintendo is finally taking a measure of pride in promoting it. After hearing some of these classic pieces done orchestrally at the Symphony of the Goddesses concert (if you have the chance, go see it, seriously) it was great to hear the same music coming out of my 3DS. Nearly all of the original music from Link to the Past has been rescored in the new game, and it is an indescribable joy to hear it again. It’s not just the music, though; nearly every sound effect is the same as I remember, but better.

A Link Between Worlds isn’t just nostalgic, however. There are a number of new pieces and several new effects that are just as good as the originals and fit perfectly into the game. I know I keep coming back to the word “balance” but that is really the best descriptor for this game: Anonuma-san and his team have found a way to both honor the Zelda series’ past while paying it all forward and refining the experience into something fresh.

In that respect, Nintendo has finally hit on the fabled “game for everyone.” A Link Between Worlds strikes just the right balance, of learning and challenge, of old and new, that it hews closest than any other modern game to the SNES days, when just about anyone could pick up a controller and have fun. Longtime fans are going to go nuts over the nostalgic gameplay, the numerous story references to the series and the Link to the Past world, both light and dark, recreated in glorious 3D. On the other hand, the game is accessible enough for new players to jump in without lengthy tutorials or a tedious refresher on the series’ storied lore.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds is one of the best games in an already legendary series. It’s a must-buy for 3DS owners this holiday, but it could also be a great way for older fans to introduce Zelda to their kids. I simply haven’t played a more satisfying game in a long, long time.

The Zelda series returns to its roots on 3DS, but uses the opportunity to introduce some fascinating new ideas. Classic gameplay, infused with fresh concepts and graced with stellar graphics and sound, make A Link Between Worlds one of the best games in the Zelda series and a must-own title this holiday.

Rating: 9.8 Exquisite

About Author

I've been gaming off and on since I was about three, starting with Star Raiders on the Atari 800 computer. As a kid I played mostly on PC--Doom, Duke Nukem, Dark Forces--but enjoyed the 16-bit console wars vicariously during sleepovers and hangouts with my school friends. In 1997 GoldenEye 007 and the N64 brought me back into the console scene and I've played and owned a wide variety of platforms since, although I still have an affection for Nintendo and Sega.

I started writing for Gaming Nexus back in mid-2005, right before the 7th console generation hit. Since then I've focused mostly on the PC and Nintendo scenes but I also play regularly on Sony and Microsoft consoles. My favorite series include Metroid, Deus Ex, Zelda, Metal Gear and Far Cry. I'm also something of an amateur retro collector. I currently live in Westerville, Ohio with my wife and our cat, who sits so close to the TV I'd swear she loves Zelda more than we do. We are expecting our first child, who will receive a thorough education in the classics.

View Profile