The Bridge Interview

Written by Charles Husemann on 4/24/2013 for

PC

More On:

The Bridge

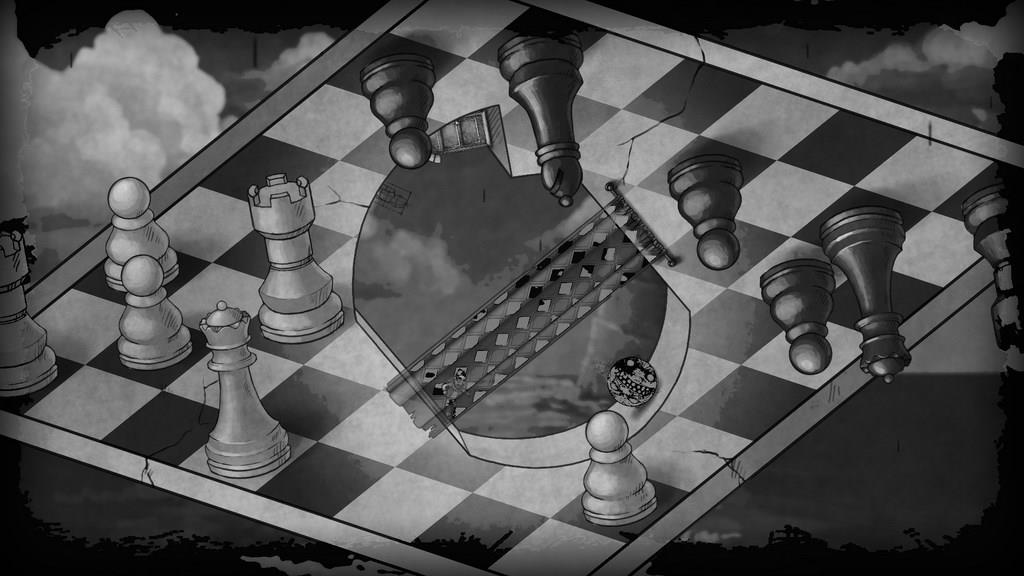

If you haven't heard of The Bridge, you're missing out on one of the more interesting indie games to come out in a while. The game was a PAX 10 winner as well as an IGF nominee, and we were intrigued enough to talk to Ty Taylor, the creator, about the inspirations behind the game and what people can expect to see when they play it.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and why you got into game development? How long have you been in the field?

I’ve been making games for as long as I can remember. Even as a small child, I would create puzzles and mazes on paper, or design my own makeshift trading card games or block puzzles. Game design has always been an obsession of mine. When I started high school, I taught myself how to program, and I’ve been making videogames ever since, for about 10 years now. Most of the videogames I’ve made in the past were experiments or small prototype games. The Bridge is the first game that I’ve spent so much time on, and I am very proud of how it turned out.

What is the inspiration behind The Bridge? Was it always going to be a puzzle game?

The main inspiration came from the artwork of M.C. Escher, but this was only after I knew the game was going to be centered around gravity control and gravity-based game concepts. At the very beginning, I was imagining this game to be a fast-paced platformer where the player controls the gravity direction, but after I thought of all the gravity-based concepts that I could include, it started feeling much more like a puzzle game to me. I eventually came up with the idea to create multiple gravity dimensions, much like you’ll see in Escher’s “Relativity” drawing. This sparked the idea to make the game Escher-centric, including impossible architecture in addition to many other Escher-esque themes.

Could you talk about the story behind the game? How did the story evolve over time?

The story of The Bridge is an area that I try not to give too much detail on, as it is intentionally ambiguous and open to a player’s personal interpretation, and figuring out the finer details of what is happening in the story is one of the magical moments of the game. But what I will say of it is that it’s about a nameless protagonist who wakes up one day to discover he has the ability to alter the direction of gravity, and he soon finds himself in a strange world with impossible architecture. The story is about his discovery of what this world is, and what events of the past led to the creation of this world. Mario and I had a framework for this storyline for several months before launch, but it actually completely solidified near the end of the production of the game. I felt that concentrating on gameplay was fundamental, and while a storyline was important, it needed to complement the gameplay and not the other way around. This is why having a completely finalized story didn’t happen until a few weeks before launch, even though most of the bits and pieces of the story had been thought up between Mario and myself for several months.

How did you come up with the idea for the time traveling mechanism? Was that always planned or was it a way to make the ease the pain of of failing puzzles?

Time-rewinding was implemented somewhat early on, but after several weeks of only having a reset option. One of the first puzzles I made in the game was one of the most difficult puzzles included in the final version, and while testing it, I found that resetting the puzzle every time I died was incredibly annoying. As a general rule-of-thumb, if you as the developer can get annoyed by your own game, so will your players. At this point, I looked towards Braid, which does a fantastic job of eliminating any fears of making a mistake through the use of time travel. While time travel isn’t a part of solving puzzles in The Bridge like it is with Braid, I still wanted to leverage this mechanic to give the same sense of safety to a player.

One of the really cool effects in the game is that when you die playing a level and reverse time, it leaves a shadow of where you died. Was that something you had planned all along or did it happen during development?

This is an effect that we came up with fairly early on in development. One of the underlying aesthetics that I wanted was for The Bridge to look like an M.C. Escher drawing had come to life. In addition to all of the subtle dynamic shading throughout the game, we added this effect when the player dies to make it look like he was getting erased, with the smudge still on the “paper,” not fully cleaned off. Likewise, we also show the player being “drawn in” for every stage, with the framing lines left to show where you started.

How did you come up with the hand-drawn look of the game? How long did it take to come up with the final look?

This hand-drawn look was the style since Mario’s first concept sketches. As soon as I had the idea of making The Bridge an Escher-themed game, I knew that I wanted it to look like and feel like an Escher drawing. I think that The Bridge unites gameplay and art very well for exactly this reason--the player can explore an Escher-esque world in what looks just like an Escher drawing. That’s why Mario and I came up with this style of art from the very beginning.

What kind of challenges does creating a physics based puzzle game present?

From a puzzle design standpoint, physics-based puzzles are often much easier to “break” than discrete puzzles. By this, I mean that playtesters often found solutions to some puzzles that I hadn’t intended while designing it, often by doing things that were much more difficult (in terms of dexterity) to carry out than the intended solution. For example, giving the player the ability to rotate gravity tends to make a player want to walk around 90-degree edges. After thorough playtesting this is no longer possible, but during the design process several playtesters were able to do this, among similar things, to “cheat” the puzzle and arrive at an unintended solution. A lot of manual reworking was required to fix a lot of these exploits to really solidify some of the puzzles to make sure players couldn’t use physics in a way they weren’t supposed to in order to break a puzzle.

The game seems like a perfect fit for a console release. Any chance you’re going to take it to the PS3, Xbox 360, or even the Vita?

I would certainly like The Bridge to be available anywhere and everywhere. I’m definitely going to start work on Mac and Linux ports soon for a Steam release, but as for consoles, that’s ultimately out of my hands, and up to the console manufactures and/or publishers. I’m optimistic that The Bridge will be available for Xbox 360/PS3/Vita/etc, but I can’t promise anything at this point, as I’m still working out the details with the distributors and publishers.

Do you have any tips for other developers who are working on their own game? What was the biggest thing you learned working on the game?

While it might sound a bit mundane, one of the biggest things I’ve learned has been time management and estimating how long it will take to complete something. It’s a mistake that I think most independent game developers make on their first major game. Back in October of 2011 at IndieCade, I was telling people that The Bridge was nearly finished and would be released soon, and this mindset of underestimating the time it would take to do something caused a lot of overambitious goals, and subsequently, some content and features were cut. The advice I’d give to new game developers would be to pick a concept which, while still being a unique and original idea, is simple enough to finish and really polish to a professional level. Often I see games that have a fantastic concept behind them be far too ambitious and never get done, and often those that do get finished are of such poor quality that if only a few more months had been spent polishing, they would have turned out substantially better.

Of the puzzles you developed, which ones stand out to you the most, either for their cleverness or pains in developing?

I’m really happy with the way all of the puzzles in the game turned out. I love watching videos of people playing through the game for the first time, and having wonderful “ah-ha!” moments when they finally figure out the solution to a puzzle. If I had to choose one, the puzzle that I’m most proud of for its cleverness has to be “The Lion,” as this one introduces a new concept to a player for the first time (the button), which is placed in such a way that he or she wants to press it immediately to figure out what happens. But while “The Lion” first appears to be simple, it requires outside-of-the-box thinking to solve it. That’s not to say that other puzzles don’t, but this one appeals to me for its cleverness because it both introduces the button and thoroughly challenges the player. As for the puzzle that caused me the most grief when in development--definitely “The Garden.” For all of the impossible architecture in The Bridge, making the perspective tricks “just work” was a tedious, manual process, and because “The Garden” is a tangled web of impossible illusions that your character seamlessly walks through, getting this to work just right took about two full weeks to make perfect. I’m really happy with the way it turned out though, so it was definitely worth the time and effort.

Is there anything we missed that you think is important?

I think that all about covers it. Thanks so much for taking the time to interview me about The Bridge. It’s been an awesome journey over the past three years, and I hope your readers enjoy playing The Bridge as much as I’ve enjoyed creating it. I can’t wait to get started on my next project!

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and why you got into game development? How long have you been in the field?

I’ve been making games for as long as I can remember. Even as a small child, I would create puzzles and mazes on paper, or design my own makeshift trading card games or block puzzles. Game design has always been an obsession of mine. When I started high school, I taught myself how to program, and I’ve been making videogames ever since, for about 10 years now. Most of the videogames I’ve made in the past were experiments or small prototype games. The Bridge is the first game that I’ve spent so much time on, and I am very proud of how it turned out.

What is the inspiration behind The Bridge? Was it always going to be a puzzle game?

The main inspiration came from the artwork of M.C. Escher, but this was only after I knew the game was going to be centered around gravity control and gravity-based game concepts. At the very beginning, I was imagining this game to be a fast-paced platformer where the player controls the gravity direction, but after I thought of all the gravity-based concepts that I could include, it started feeling much more like a puzzle game to me. I eventually came up with the idea to create multiple gravity dimensions, much like you’ll see in Escher’s “Relativity” drawing. This sparked the idea to make the game Escher-centric, including impossible architecture in addition to many other Escher-esque themes.

Could you talk about the story behind the game? How did the story evolve over time?

The story of The Bridge is an area that I try not to give too much detail on, as it is intentionally ambiguous and open to a player’s personal interpretation, and figuring out the finer details of what is happening in the story is one of the magical moments of the game. But what I will say of it is that it’s about a nameless protagonist who wakes up one day to discover he has the ability to alter the direction of gravity, and he soon finds himself in a strange world with impossible architecture. The story is about his discovery of what this world is, and what events of the past led to the creation of this world. Mario and I had a framework for this storyline for several months before launch, but it actually completely solidified near the end of the production of the game. I felt that concentrating on gameplay was fundamental, and while a storyline was important, it needed to complement the gameplay and not the other way around. This is why having a completely finalized story didn’t happen until a few weeks before launch, even though most of the bits and pieces of the story had been thought up between Mario and myself for several months.

How did you come up with the idea for the time traveling mechanism? Was that always planned or was it a way to make the ease the pain of of failing puzzles?

Time-rewinding was implemented somewhat early on, but after several weeks of only having a reset option. One of the first puzzles I made in the game was one of the most difficult puzzles included in the final version, and while testing it, I found that resetting the puzzle every time I died was incredibly annoying. As a general rule-of-thumb, if you as the developer can get annoyed by your own game, so will your players. At this point, I looked towards Braid, which does a fantastic job of eliminating any fears of making a mistake through the use of time travel. While time travel isn’t a part of solving puzzles in The Bridge like it is with Braid, I still wanted to leverage this mechanic to give the same sense of safety to a player.

One of the really cool effects in the game is that when you die playing a level and reverse time, it leaves a shadow of where you died. Was that something you had planned all along or did it happen during development?

This is an effect that we came up with fairly early on in development. One of the underlying aesthetics that I wanted was for The Bridge to look like an M.C. Escher drawing had come to life. In addition to all of the subtle dynamic shading throughout the game, we added this effect when the player dies to make it look like he was getting erased, with the smudge still on the “paper,” not fully cleaned off. Likewise, we also show the player being “drawn in” for every stage, with the framing lines left to show where you started.

How did you come up with the hand-drawn look of the game? How long did it take to come up with the final look?

This hand-drawn look was the style since Mario’s first concept sketches. As soon as I had the idea of making The Bridge an Escher-themed game, I knew that I wanted it to look like and feel like an Escher drawing. I think that The Bridge unites gameplay and art very well for exactly this reason--the player can explore an Escher-esque world in what looks just like an Escher drawing. That’s why Mario and I came up with this style of art from the very beginning.

What kind of challenges does creating a physics based puzzle game present?

From a puzzle design standpoint, physics-based puzzles are often much easier to “break” than discrete puzzles. By this, I mean that playtesters often found solutions to some puzzles that I hadn’t intended while designing it, often by doing things that were much more difficult (in terms of dexterity) to carry out than the intended solution. For example, giving the player the ability to rotate gravity tends to make a player want to walk around 90-degree edges. After thorough playtesting this is no longer possible, but during the design process several playtesters were able to do this, among similar things, to “cheat” the puzzle and arrive at an unintended solution. A lot of manual reworking was required to fix a lot of these exploits to really solidify some of the puzzles to make sure players couldn’t use physics in a way they weren’t supposed to in order to break a puzzle.

The game seems like a perfect fit for a console release. Any chance you’re going to take it to the PS3, Xbox 360, or even the Vita?

I would certainly like The Bridge to be available anywhere and everywhere. I’m definitely going to start work on Mac and Linux ports soon for a Steam release, but as for consoles, that’s ultimately out of my hands, and up to the console manufactures and/or publishers. I’m optimistic that The Bridge will be available for Xbox 360/PS3/Vita/etc, but I can’t promise anything at this point, as I’m still working out the details with the distributors and publishers.

Do you have any tips for other developers who are working on their own game? What was the biggest thing you learned working on the game?

While it might sound a bit mundane, one of the biggest things I’ve learned has been time management and estimating how long it will take to complete something. It’s a mistake that I think most independent game developers make on their first major game. Back in October of 2011 at IndieCade, I was telling people that The Bridge was nearly finished and would be released soon, and this mindset of underestimating the time it would take to do something caused a lot of overambitious goals, and subsequently, some content and features were cut. The advice I’d give to new game developers would be to pick a concept which, while still being a unique and original idea, is simple enough to finish and really polish to a professional level. Often I see games that have a fantastic concept behind them be far too ambitious and never get done, and often those that do get finished are of such poor quality that if only a few more months had been spent polishing, they would have turned out substantially better.

Of the puzzles you developed, which ones stand out to you the most, either for their cleverness or pains in developing?

I’m really happy with the way all of the puzzles in the game turned out. I love watching videos of people playing through the game for the first time, and having wonderful “ah-ha!” moments when they finally figure out the solution to a puzzle. If I had to choose one, the puzzle that I’m most proud of for its cleverness has to be “The Lion,” as this one introduces a new concept to a player for the first time (the button), which is placed in such a way that he or she wants to press it immediately to figure out what happens. But while “The Lion” first appears to be simple, it requires outside-of-the-box thinking to solve it. That’s not to say that other puzzles don’t, but this one appeals to me for its cleverness because it both introduces the button and thoroughly challenges the player. As for the puzzle that caused me the most grief when in development--definitely “The Garden.” For all of the impossible architecture in The Bridge, making the perspective tricks “just work” was a tedious, manual process, and because “The Garden” is a tangled web of impossible illusions that your character seamlessly walks through, getting this to work just right took about two full weeks to make perfect. I’m really happy with the way it turned out though, so it was definitely worth the time and effort.

Is there anything we missed that you think is important?

I think that all about covers it. Thanks so much for taking the time to interview me about The Bridge. It’s been an awesome journey over the past three years, and I hope your readers enjoy playing The Bridge as much as I’ve enjoyed creating it. I can’t wait to get started on my next project!

About Author

Hi, my name is Charles Husemann and I've been gaming for longer than I care to admit. For me it's always been about competing and a burning off stress. It started off simply enough with Choplifter and Lode Runner on the Apple //e, then it was the curse of Tank and Yars Revenge on the 2600. The addiction subsided somewhat until I went to college where dramatic decreases in my GPA could be traced to the release of X:Com and Doom. I was a Microsoft Xbox MVP from 2009 to 2014. I currently own stock in Microsoft, AMD, and nVidia.