Building Blocks

Written by Randy Kalista on 11/15/2012 for

360

PC

More On:

Minecraft

It's 1989. I'm eleven years old. I cross a cold parking lot with my parents to the Fred Meyer shopping center, shoving my hands into my pockets. Five- and six-foot-tall pine trees, fresh cut, line the front of the building. A skinny man in a Santa outfit rocks back on his heels at the entrance, ringing a tiny silver bell. He hollers a "Ho ho ho!" I'm startled by the store's new automatic sliding doors.

My dad hands me two quarters pinched between his thumb and forefinger. This is a red-letter day. On most trips into town I have to make due with one quarter. I accept the fifty cents with a fist pump and a "Yessss!" It doesn't occur to me for one moment that I could drop one of those quarters into a Salvation Army donation bucket. The thought doesn't cross my mind.

My dad hands me two quarters pinched between his thumb and forefinger. This is a red-letter day. On most trips into town I have to make due with one quarter. I accept the fifty cents with a fist pump and a "Yessss!" It doesn't occur to me for one moment that I could drop one of those quarters into a Salvation Army donation bucket. The thought doesn't cross my mind.

I edge past Skinny Claus and dodge sale signs and shopping carts. I head for the arcade machines lined up next to the restrooms. The strings of Christmas lights, the buzz of overhead florescence, the lottery ticket vending machines--all of that fades when I see that stand of arcades.

Groups of adolescents stare into flickering video game screens. Quarters queue up along joystick panels. "I got next," someone says, and another quarter props up against the lower edge of a game screen. There's a half-full ash tray and a soda-sticky floor in front of a 1943 machine. With typically only twenty-five cents in my hand, I have to spend wisely. That means no fighting games; Karate Champ is out. No co-op either; I don’t want anyone commenting on how many times my warrior needs food badly. And Dragon's Lair is never an option; I've never seen so many death scenes before or since.

That left the minigame mayhem of Tron with its blue-glowing joystick, Star Wars' vector-graphics assault on the Death Star, or the mundane (by comparison) brick-bashing of Arkanoid. With double my arcade allowance, I have a go at Star Wars. The bombardier strands of flashing asterisks and spinning TIE Fighters make short work of me. I let the continue counter run down to zero.

I step over to the unpopulated Arkanoid machine and breathe deep. I like blocks. With a paddle running along the bottom of the screen and a ball bouncing off predictable geometries, Arkanoid gives this one-quarter-left kid a lot of bang for his buck. Someone watches over my shoulder for a minute as I play, but his quarter doesn't clack up onto the joystick panel. He moves on.

I'm an 8-bit John McEnroe on the Pong-like Arkanoid. But eventually the blocks get the better of me and I can't keep my eye on the ball. Game over.

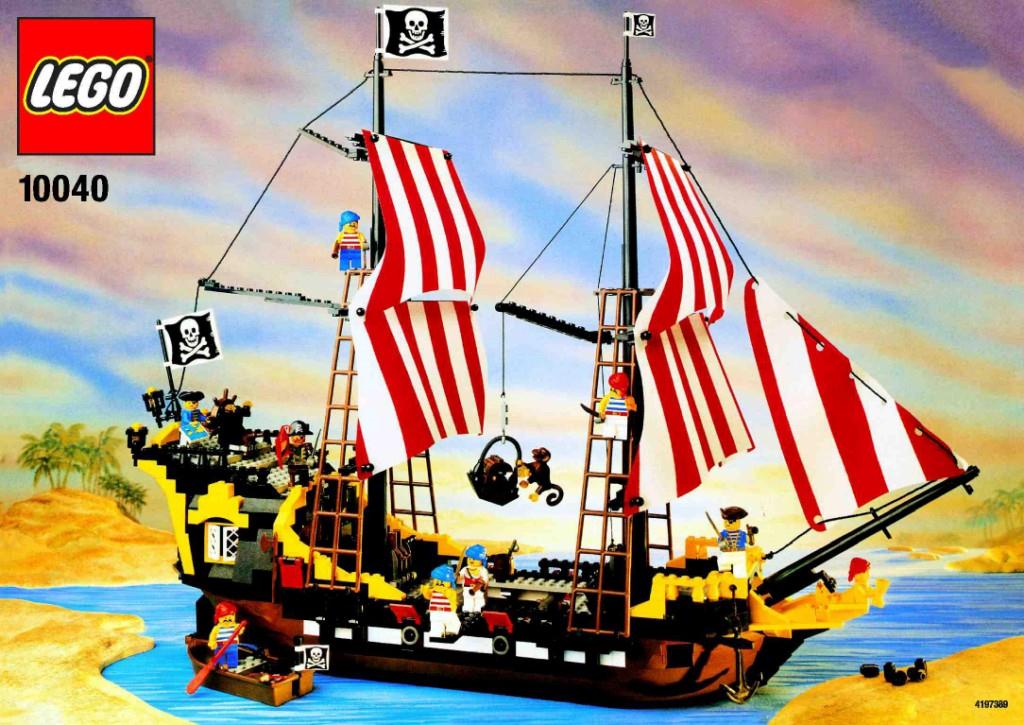

I dodge sale signs and shopping carts on my way to the LEGO aisle. I sit down in front of a large box standing on the bottom shelf. It's the Black Seas Barracuda: a pirate ship with striped sails, skull-and-crossbones flags, and firing cannons, two to a side. The face of the LEGO box opens like an immense book cover, revealing more scenes of piracy and clear plastic windows into the blocks nested inside.

I sit down on the tile floor. It may be a long wait before my parents finish shopping and come find me. Not that they'll be surprised to find me sitting exactly where I'm sitting. I've been camping on this spot for months. I play a video game and then sit down in front of this particular LEGO ship. This is what I do at eleven years old.

"Son," my dad says. He's standing at the far end of the aisle. "Time to go," he says. I look over at him, the immense Black Seas Barracuda box overwhelming in my lap. I look back at the box. Back at him. Now back to the box. I'm trying to convey a message here. I hope he gets it. It's possible he hasn't gotten the hint after months of me making a bee-line for this LEGO box, sitting in the aisle with it sprawled in my lap, and waiting for him to come find me. I struggle to put the box back on the shelf. It's gotten heavier in my arms. It's gained all the weight of my expectations for a perfect Christmas morning.

"You've got plenty of blocks already, boy. They're at home."

But, just days before Christmas, I see a box with the exact length, width, and height of the Black Seas Barracuda appear under the tree. I haven't touched my other LEGO blocks. I can't build a pirate ship out of my existing collection. I have no imagination.

It's 2011. I'm 33 years old. I'm playing Minecraft for the first time. My one-year-old daughter will be asleep for the next ten hours. My wife will be streaming Netflix for the next two. In Minecraft, sand and water spread out behind me, trees and hills rise up in front of me. I build a small sandcastle for me to fit into; straight walls, square corners, flat roof.

It will be awhile before anyone uploads a video of their scale-model replica of the Starship Enterprise. No one has yet recreated Harry Potter's Hogwarts or Helm's Deep from The Lord of the Rings. I haven't seen the monumental, pixelated constructions of 2-D sprite characters like Super Mario, Goomba, and Yoshi. And even without seeing those, I know my own constructs are weak.

So I explore, the piano-tinkling soundtrack tiptoeing around the world with me. The topography crests in waves and falls to its own death off steep cliffs. The trees huddle in places and scatter in others as I run and jump up the ziggurat-like steps of a cloud-high mountain.

I like blocks. But I don't know what to build. I have no imagination. Never have, really.

I watch instructional videos on YouTube teaching me how to survive my first 15 minutes, but I'm determined to make my own mark on the land, to build my own thing, to draw my own skyline, to cut a brand new architectural silhouette against the square sky. But as much as my mind huffs and puffs, I can't picture what to make.

I dig a square chamber below ground level. I dig a square staircase spiraling down into so much coal and iron. I clean up the facade of my hillside entrance. But I accomplish so little.

I once heard that if you are bored, then you are boring. And here I am, getting bored. Until I remember something else I once heard. This time from my dad.

"You've got plenty of blocks already, boy. They're at home."

So I throw aside my lack of imagination and lack of building blueprints and lack of a LEGO box depicting plunder and looting against a gift-wrapped backdrop. I look up from my laptop in the living room and see my wife on our low green couch, our first major home purchase since buying our home. I see the oak dining table that seats six with the leaflet wedged the middle. I see my brother-in-law's Baldwin piano we're keeping safe until he lives in something bigger than his San Francisco apartment. I see our bookshelves stuffed with books we've only read once, or never.

Looking around, I find my instructions. And I build my home.

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile