SBK X

This time I knew that I’d have to be gentle when shifting my weight as I worked through the long right-hand turn. If I felt myself turning too tightly, anything more that a gentle weight shift to the outside would start a drift to the outer edge of the track that I more than likely would not recover from. Just past the apex of the turn, I started feeding in some power, ready to release a little of the tension on the throttle when (not if!) the back tire started to jump away from the direction of the turn.

It was in the second of the two Lesmo turns that I fell victim to a moment of complacency. Eager to gain ground on the racer in front of me, I was a little too aggressive with the throttle and the back tire responded, as it always does when I get too enthusiastic, with a slide towards the outside of the turn, but this time much more violently. Surprised, I rolled the throttle all the way out. Inevitably, the sliding tire regained its grip on the asphalt surface at the worst possible moment, causing the motorcycle to violently shift in the other direction. My rider was vaulted over the top of the bike and flung violently down the race track in a classic High-Side wreck. Maybe I wasn’t getting the hang of it after all. Perhaps I should have just stayed in Arcade mode.

Published by Deep Silver, Milestone’s SBK X Superbike World Championship had humbled me like no other racing game had ever done. It was to be expected, really, since my experience with riding motorcycles didn’t survive that night more than 30 years ago when I was collared by a county sheriff for illicitly riding a co-worker’s Honda “like a damned fool.” Hey, it’s not like I was jumping it all that high. I suppose he might have been more forgiving had it not been a street bike that I was throwing around in that dark parking lot after work...

As I mentioned above, my initial inclination was to use the Arcade mode as a sort of virtual training wheels and move up to Simulator mode once I had gotten the hang of it. The problem turned out to be that Arcade mode simply dumbs down the physics model to a degree that really doesn’t provide much of an idea of what to expect upon graduation to the more difficult model. And, of course, there was that stupid and completely ineffective “boost” button. There was no real point to it; pressing the boost button did increase the perception of speed, but it didn’t increase the actual speed of my bike as referenced to the guy in front of me. It was a hokey feature in want of an actual goal, it seems to me. Thankfully it was easy enough to simply ignore it.

After a few hours in Arcade mode, I thought I was ready to move up to the more sophisticated Simulation mode, but as it turns out I was simply unprepared for the steering lag introduced by having to shift the rider’s weight to get the bike to turn. Even worse, I was not ready for the seemingly ponderous way the weight shifts as compared to the more nimble Arcade mode. It was particularly noticeable in the middle of chicanes; I could get through the first turn, but always ended up going wide on the second turn. This is, of course, known as ‘realism’ and is generally considered to be a good thing when talking about simulators, so don’t read this as a complaint. Once I started to get a better feel for it, I actually began to enjoy it. It’s ever so much more challenging than just turning a steering wheel and having the vehicle respond almost instantly. It takes much more planning and subtle control than something like a Formula 1 car with its massive down force-producing wings and wide, grippy tires. The coolest thing, though, was the ability to pull wheelies and hold them for extended periods. Not so cool was braking hard into a turn using the front brake (which, being activated by the left trigger finger, is the easiest to use) while having the rider’s weight shifted forward. That resulted in an embarrassing over-the-handlebars tumble. Lesson learned!Unfortunately, with my dearth of real world motorcycle racing experience I won’t be able to provide a credible opinion regarding the true realism of the physics model and whether or not it will satisfy the hard core racing crowd. I can say that it feels like what I would expect it to feel like, for whatever that’s worth. What I can also say (and this ain’t nothing) is that it’s fun! Once I got to the point where I could keep up with the pack at the Amateur setting, having found that Rookie was much too easy, I really enjoyed the feeling of racing around in a line, all of the bikes streaming out in front of me in a kind of conga line. Accelerating out of a turn, watching the other riders struggle with the balance between the fastest possible line and the risk of sliding the back wheel right out from under the bike, flying down the straights hoping to get an edge on the guy in front of me while braking into the next turn, and actually making a pass now and then was a terrific rush.

About half of the 14 tracks were familiar to me from other racing games so there were plenty of venues for me to race at without having to learn the intricacies of a new track map. That allowed me to spend more time trying to get a feel for my mount. I found that the best practice was to use the Quick Race mode and select one of the lower horsepower series. The weaker bikes were a little bit more forgiving. I also stayed in the ‘low’ simulation setting to avoid having to spend any time thinking about complexities like forward and backward weight shifting. I also found the “Evolving Track” feature to be quite useful. After a few laps, the track would start to get rubbered in. Not only did this provide a nice visual guide to the braking points and racing lines being used by my competitors, it also provided a little more grip for my tires. The effects of the evolving track were also quite noticeable when I set up a few races on wet tracks; the racing line dried out quicker than the rest of the track.

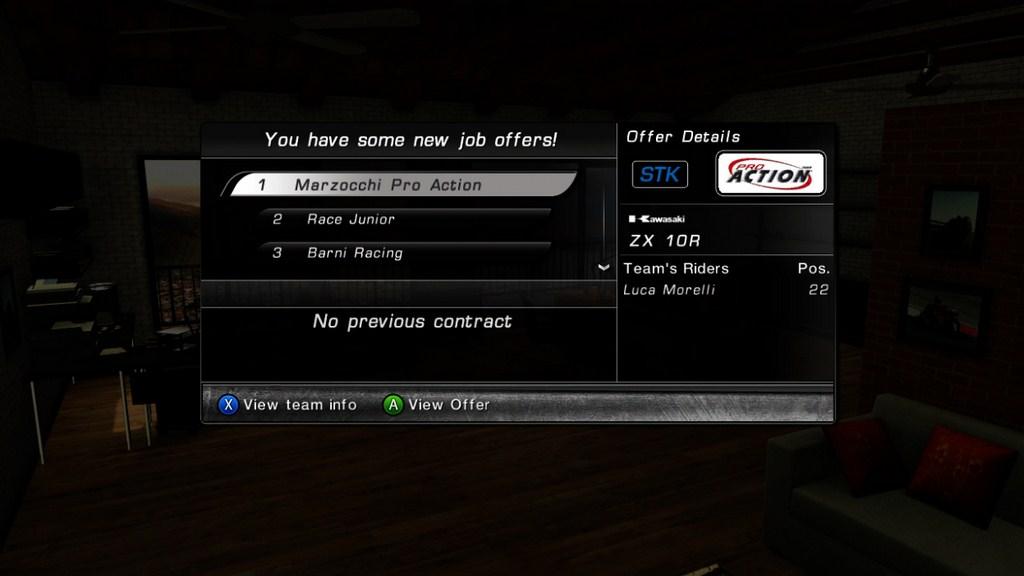

With the multitudinous configuration features offered by the Quick Race mode, I didn’t much see the need for the more structured modes. For those that prefer it, there is a Career Mode that will take the racer through eight seasons of racing and allow a player to experience a more complete competitive experience. Sitting mid-point between the two extremes of Quick Race and Career Mode is Quick Championship, a mode that will take the player through a single season pass through all fourteen of the available tracks. I think that particular mode strikes a perfect balance between playability and drudgery.

For those looking for the ultimate challenge, the simulation mode allows the rider to configure many of the settings on the bike. Naturally there aren’t any aerodynamic settings to fool with, but the suspension, steering angles, brakes, and transmission can all be adjusted to provide better handling on the track. There is also a telemetry feature to assist in analyzing the differences in track performance resulting from changes made to the bike’s setup. I found that my pitiful riding skills were not sufficiently in tune with the bike for actual mechanical tuning of the bike to make any difference to me. Maybe with a few months of practice I can get to the point where that level of customization becomes attractive to me; for now it’s just nice to know that it’s there.

Against my better judgement, I actually tried to get into a multiplayer race on Xbox Live, even though I knew that I’d get my helmet handed to me in any kind of fair race. I worried for naught; there were no opponents to be found. It seems that multiplayer racing will require you to find and coordinate with some online friends if you want to give it a go. I found it to be quite simple to set up a racing session, though, so had there been anyone out there willing to jump in it looks like it would have been very easy to do.

It’s traditional to spend a few words describing the quality of the graphics and sounds, although I find that the current baseline for these things is now pretty high. In other words, I found both the graphics and sounds in SBK X to be pretty much what I expected: very good. The tracks are detailed enough to provide good landmarks for gauging the correct entry point into turns, and there are enough ancillary details to provide a fairly decent feeling of “being there.” The sounds of the motorcycles are very realistic, or as I said before, realistically similar to what I imagine an actual racing bike would sound like.

With the easily accessible Arcade mode and the great degree of customization of the difficulty level in the more complex Simulator mode, SBK X will appeal to rank amateurs and devoted motorcycle racing fans alike. As with most console-based racing sims, the standard controller doesn’t come anywhere near providing a natural feeling of control, but the accurate modelling of the physics does provide some “feeling” of the weight shifting that is such a central component to steering a motorcycle. The racing at the higher AI skill levels is very challenging but the lower levels provide plenty of action for the less experienced rider. With practice, even a novice rider will see improvement in their performance and will be rewarded with higher degrees of satisfaction as they find themselves getting better. And really, that’s about the most important thing you can ask for from a game.

Rating: 8.5 Very Good

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been fascinated with video games and computers for as long as I can remember. It was always a treat to get dragged to the mall with my parents because I'd get to play for a few minutes on the Atari 2600. I partially blame Asteroids, the crack cocaine of arcade games, for my low GPA in college which eventually led me to temporarily ditch academics and join the USAF to "see the world." The rest of the blame goes to my passion for all things aviation, and the opportunity to work on work on the truly awesome SR-71 Blackbird sealed the deal.

My first computer was a TRS-80 Model 1 that I bought in 1977 when they first came out. At that time you had to order them through a Radio Shack store - Tandy didn't think they'd sell enough to justify stocking them in the retail stores. My favorite game then was the SubLogic Flight Simulator, which was the great Grandaddy of the Microsoft flight sims.

While I was in the military, I bought a Commodore 64. From there I moved on up through the PC line, always buying just enough machine to support the latest version of the flight sims. I never really paid much attention to consoles until the Dreamcast came out. I now have an Xbox for my console games, and a 1ghz Celeron with a GeForce4 for graphics. Being married and having a very expensive toy (my airplane) means I don't get to spend a lot of money on the lastest/greatest PC and console hardware.

My interests these days are primarily auto racing and flying sims on the PC. I'm too old and slow to do well at the FPS twitchers or fighting games, but I do enjoy online Rainbow 6 or the like now and then, although I had to give up Americas Army due to my complete inability to discern friend from foe. I have the Xbox mostly to play games with my daughter and for the sports games.

View Profile